This paper seeks to connect the archive and the family through photography. I argue that the family photograph bears shifts in identity by virtue of the archival context it is found in, and that the character of image archives themselves is determined by the affective potential of the photographs that they hold. Vast differences in photographic and institutional particularities make any coherent definition of the archive difficult, with the family oscillating between being in bright focus or in the shadows of different collections. For the majority of this essay, a range of examples from India will reveal the negotiations that are involved in housing family photographs, indicative of the polyphonous reality of archives.

If every family has its own internal archive, such as a family album, then what roles do formal archives of the state or universities or private institutions in possession of such images perform? Does the transfer of family photographs from the home to the shelves or servers of these institutions simply aid preservation or does it also transform their meanings? What are the expectations from discovering and reconstructing visually guided histories of family photographs in institutional archives or homes?

If objects were to speak, the family album would lament its removal from the home, for this would indicate a departure from the primary context, its reason for existence. There could be a dissolution of ties, death of memory, neglect, or aversion toward the image that caused its ejection from the family. A lack of space for the printed image and the negatives, or full computer hard drives with not enough memory for digitized versions, are the commonly cited reasons for selling, discarding, or deleting bulky albums. And yet it is when the family photograph leaves the home that the gains and losses of its meanings begin, that it acquires a biography and membership of archives with alternative logics. In a paradoxical sense, this departure is therefore both depleting and enriching for the photograph.

The family home, the studio, the institutional archive, the museum, and the commercial establishment are all places of rest for photographs, although this is an uncomfortable rest because the potential for movement is always present, never allowing meanings to solidify. The multiplicity of each photograph has given rise to many possible arrangements and classifications. One type of archive often mutates into another; the family photograph that travels into a digital archive or an institution accumulates and loses meanings with changing contexts. The political histories of nations, the economic compulsions of institutions, and the cultural inclinations of collectors transform archival frameworks, thereby rendering archival contents malleable. The family photograph often makes a long and complex journey through across archival narratives that need acknowledgement at the time of meaning construction. The thrust of this paper will be toward the expansion of the concept of the archive to include informal and sometimes inaccessible spaces, such as family homes, and the hidden histories that these hold.

Without restricting my study to a singular methodology of reading family photographs, I will analyze four photographic archives from India, followed by two contemporary artistic responses on the subject. I hope to bring to light the possible destabilization of known histories and the multiplicity of meanings offered by family photographs in the archive.

6.1 Between the home and the archive

Alluding to the different contexts of collecting, photography historian Malavika Karlekar outlines three ways to read the image. The usual one is to view the image as something of general interest, as a record of the past, or as a mnemonic device. Second, the photos may become part of a more specific interpretive or interrogative exercise, adding a significant dimension to accepted history. The third kind of reading is the act of interpreting “orphaned” photographs, visuals that viewers such as Karlekar herself have “chanced upon or sourced without knowing too much about them per se, but only that they fitted into the period and frame of study” (Karlekar 2005, 166–167). I propose extending this method to include all three stages of reading to the same artefact: if we were to begin reading the family photograph by treating it as a mnemonic device, its peculiarities may soon suggest alternatives to historical facts, while the “adoption” of “orphaned” images would further expand embedded meanings that have remained hidden to date. From the archival perspective, these multi-tiered meanings confront the viewer who may be unprepared for a lack of closure, or a constant deferral of the final reading of these photographs.

As a preliminary example, in a film titled Family Album (2011), directed by Nishtha Jain, the figure Subhamita Chaudhuri says simply of her family’s images that “these photographs are a part of my life. I have grown up looking at them.”1 They act as mnemonic tools for Subhamita to meet and converse with departed relatives, reconstruct their lives and glean the role of the camera in the family in bygone times. The narrative undercurrent in the Chaudhuri family archive seems to evoke feminine histories, unacknowledged in family trees and other written documents, alive only in visually guided oral recollections. This family’s self-identity is articulated through verbal reminiscences of events, personalities, and dialogues associated with the people in the photographs, yet the fragility and flexibility of memory make the reconstructions contingent. The Chaudhuri family exemplifies Marianne Hirsch’s theorization of the “familial gaze,” defined as “the conventions and ideologies of family through which they see themselves” (Hirsch 1997, 51). Familial belonging can be read into the folds of a grandmother’s sari, the toys strewn around aunts as babies, and the sunlit corridors of family homes, recollected by the quivering voices of the women in the Chaudhuri family. At a second level, one may examine Jain’s directorial choices in making such a film, with impassioned voice-overs and an emotive sound score permeating the way we receive the Chaudhuri family’s photographs—full of poignancy and nostalgia for a lost era of elite living in India’s colonial capital.

Fig. 1: Subhamita Chaudhuri, from Nishtha Jain’s film Family Album, 2011.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. hicollage6_1

As characters in the film die even before the documentary project is completed, the Chaudhuri family photos become “orphaned” or “found” images, losing subjective meaning while benefiting from historical attribution of time, space, and cultural signification. The reception of the Chaudhuri photographs in a digitized archive would strip them of such subjectivities, as they would appear numbered and cataloged for a reconstruction along any of the trajectories of architecture, textiles, and education in the late nineteenth century in Calcutta’s bid for modernity (see Fig. 1 and in addition Figs. 2–4 in Hyperimage).

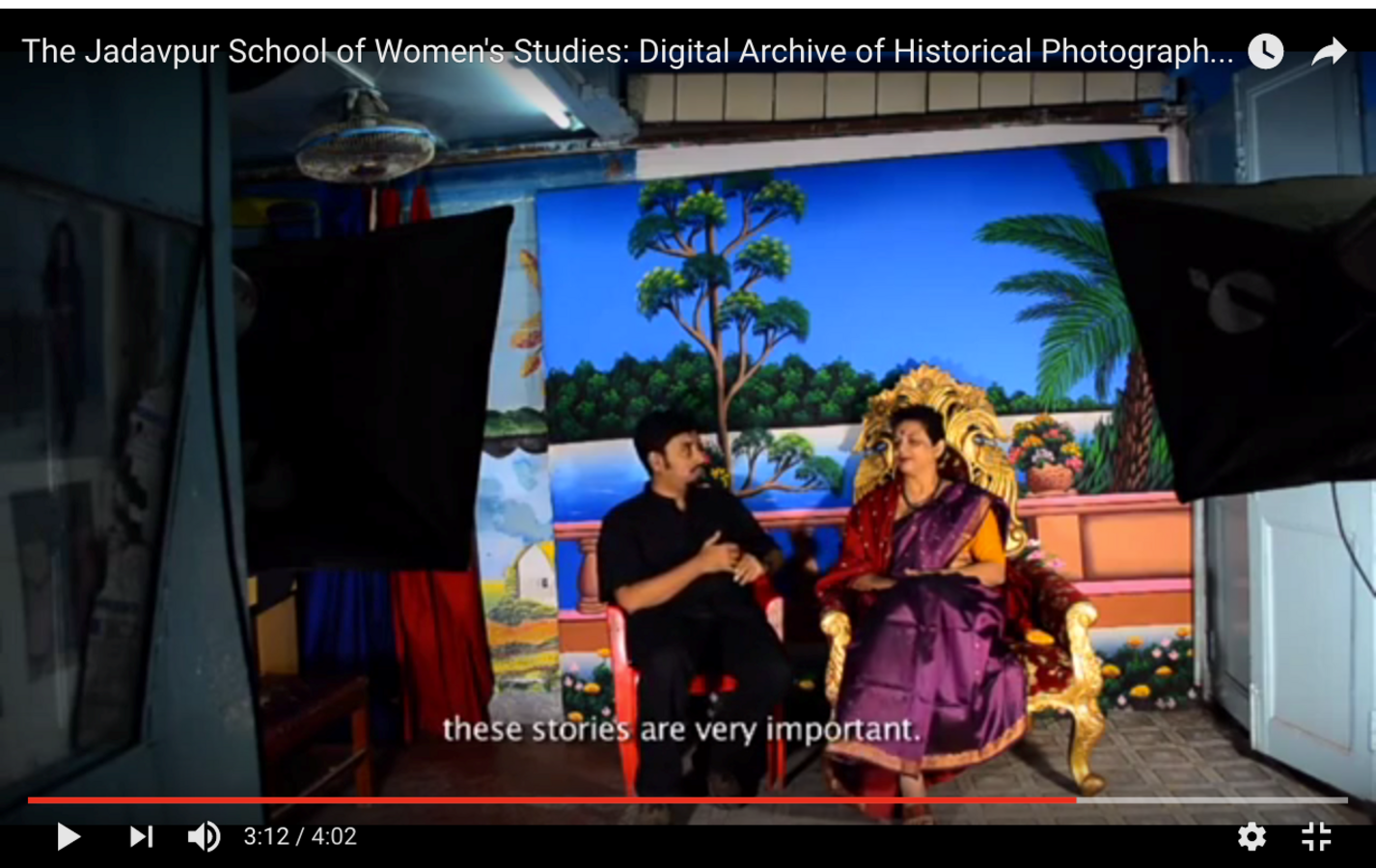

The first institutional archive that I discuss is perhaps closest to the family home. The School of Women’s Studies at Jadavpur University in Calcutta received an India Foundation for the Arts grant in 2007 to collect, archive, and read the economy of photographs, photographic practices and their modes of representing the lives of urban middle-class Hindu women in Bengal from the 1880s to the 1970s. The photographs were acquired from various sources such as neighborhood photo studios, private collections, and families. The intention of this archive was, over a period of two years, to rescue old photographs from damage or loss and curate them in a way that would facilitate fresh analysis of the photographic cultures of urban middle-class Bengali women in their dominant modes of representation. The main archivist and curator, Hardikbrata Biswas, believed that the recontextualization of women’s photographs in relation to their past that “played out in spaces that were potentially colonized, infiltrated by patriarchy into private areas of consumption, reproduction, leisure and entertainment” needed to be challenged.2 Readings of photographs were invited from within and beyond the family fold, in order to fully realize their potential of meaning-making. New connections between the subjects photographed, the cultural world that they inhabit, as well as the interplay between the photographer and the sitter would give rise to new theoretical formulations (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Hardikbrata Biswasand Samita Sen, in conversation about the archive Family Album, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, film still from Youtube.

Phase one of the project saw the documentation, digitization, and archiving of photographs from Kolkata and other districts of West Bengal. After the classification and digitization of roughly 10,000 photographs, the hard copies were returned to the owners, thus restoring the album to the contextual bedrock of the family. This step ensured that no stories were lost to the owners of the albums, that their inheritance remained intact. The documentation process involved extensive interviews with the owners of the albums,3 contributing to the content of an anthology of critical essays that was subsequently published. The archive chiefly contributed to a larger project by the same department at Jadavpur University, titled Re-Negotiating Gender Relations in Marriage: Family, Class and Community in Kolkata in an Era of Globalization.

A subsequent paucity of funds led to the unfortunate closure of the project, rendering the archive inaccessible to the world. The initial effort to open up intimacies of home and family through photography ended with their regression into the same depths from which they first came, making further expansion, extraction, or extrapolation impossible. It is as if the most primal stories of photographs seeking to emerge from the bedrock of the family fell short of flight, for the gravity of the home embedded them into their spaces of birth and primary meaning again.

Next is an older and larger collection of images that resides at the Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Archive of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. This nodal institution hosted several important members of the Subaltern Studies Group and developed its visual and material archive from diverse sources within the Bengal region. Established in 1993, the Archive has now expanded to include “popular prints and paintings, modern art, studio, family, salon, commercial and news photography, advertisements and commercial art, posters, covers, labels, hoardings and other publicity material.”4 It is also a part of larger archival initiatives in the world such as the Endangered Archives Programme of the British Library and is in the process of collaborating with the South Asia Materials Project (SAMP) to further expand access. It runs with an open access policy, although seeking permission from donors for the reproduction of images (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: The Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Archives, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, courtesy of Ritwika Misra, 2017.

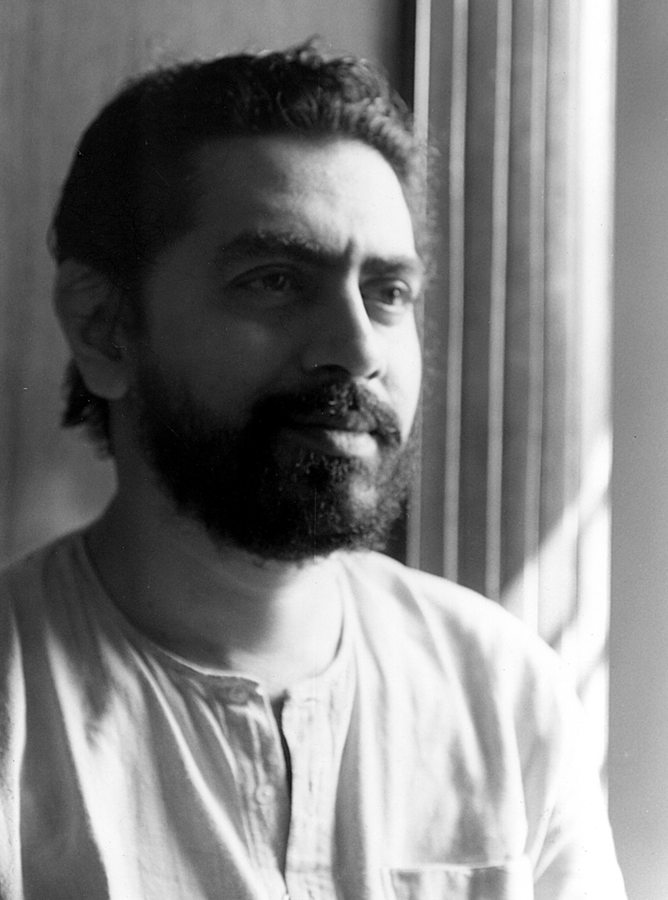

The photographs collected by this archive are nomenclatured according to the donor, cutting across the usual larger categorizations. One such seminal collection is attributed to Siddhartha Ghosh. The images that now belong to his unclaimed estate, inaccessible after his death in 2002, were fortunately digitized at the centre in 1999. Originally a scientist at the Central Glass and Ceramic Research Institute, Ghosh was associated with the center in the 1990s. His keenness to explore Bengali photographic history propelled him into the lives and private collections of important and ordinary figures of his time whom he befriended. These included the family of poet laureate Rabindranath Tagore, historian Barun De, and Maharaja Birchandra, prince of the kingdom of Tripura, among others. He did not have a singular, organized method of acquiring the images, with several of them being “borrowed” from friends never to be returned. Archiving was not a professionalized or even organized system at the time, apart from government initiatives to survey and document the architecture and people of India, giving Ghosh exceptional freedom and access that was not always uniform or systematic. Although these photographs were extracted from their original locations, they benefited from Ghosh’s affective and scholarly investments, and helped develop the first regional history of Indian photography in his publication titled Chhobi Tola: Bangalir Photography Charcha (Tola 1988).5 During his own lifetime, several families opened their albums for Ghosh to select images from, his impulse to preserve these images terminating with his death. His own family lay no claim to his collection, and it fell to the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC) and its research initiatives to form interconnections and linkages, finding friends and relatives for photographs within the archive (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Portrait of Siddhartha Ghosh, late twentieth century, courtesy of Sanjeet Chouwdhury and the Hiteshranjan Sanyal Archives, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.

The 2011 exhibition The City in the Archive: Calcutta’s Visual Histories (Guha-Thakurta 2011) displayed, among several other things, Siddhartha Ghosh’s collection. The show was organized under three headings: photographs from studios in the city, from family albums, and those of individual donors. Of particular interest were photographs from Calcutta homes, including cabinet cards from famous studios, wedding portraits with child brides, self-portraits, and family cameos. The true value of the exhibition surfaced in its reception, as people recognized their ancestors, identifying them and adding to the archive’s knowledge base. As such, the Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Archive succeeds in the aims of Family Album at Jadavpur University, mentioned above. It allowed new interconnections to surface between home and institutional archive, between subjective narratives of image donors and scholarly research informed of historical externalities.

A contrast to the two archives already discussed is the much larger collection of photographs at the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in New Delhi, spanning a shorter period of time but a regionally wider scope. The collection stems from the initiative of Ebrahim Alkazi, who as an art connoisseur, collector, and bibliophile began acquiring photographs in the 1980s. Its previous locations in New York and London have situated the archive internationally as a leading repository of Indian artefacts, bearing a format and reputation that correlate to international standards and methods of preservation. Here, one can find the greatest names in Indian colonial photography such as Samuel Bourne, Lala Deen Dayal, Cecil Beaton, and Felice Beato. The subjects of the images vary from architectural views of cities such as Lucknow and the erstwhile Vijayanagara Empire to portraits of royalty such as the Begums of Bhopal, exquisite platinum prints of the Nepalese royal family’s portraits to affordable postcards and cabinet cards of exotic destinations and dancing girls, subsumed under “bazaar art.” The archive in New Delhi holds all the images in hard copy, meticulously preserved in dehumidified rooms and acid-free sleeves with a digitized catalog (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8: View of the storage and archival research at the Alkazi Foundation, photo taken from the Alkazi Foundation’s website.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

The visual material here can be divided into two groups: on the one hand, images originating from families produced for their pleasure and “memory” and, on the other hand, images mass produced in multiple copies for commercial sale and circulation, in the form of postcards or souvenir albums. While the history of the latter is easy enough to trace from the detailed versos, the family albums espouse a certain loss as they remain devoid of personal history, with no names to faces, events and contexts forgotten forever. Recalling Karlekar’s differentiation between the various ways of reading photographs, even though the internal mnemonic narratives of such images remain obscured, valuable larger social and historical readings may be established.

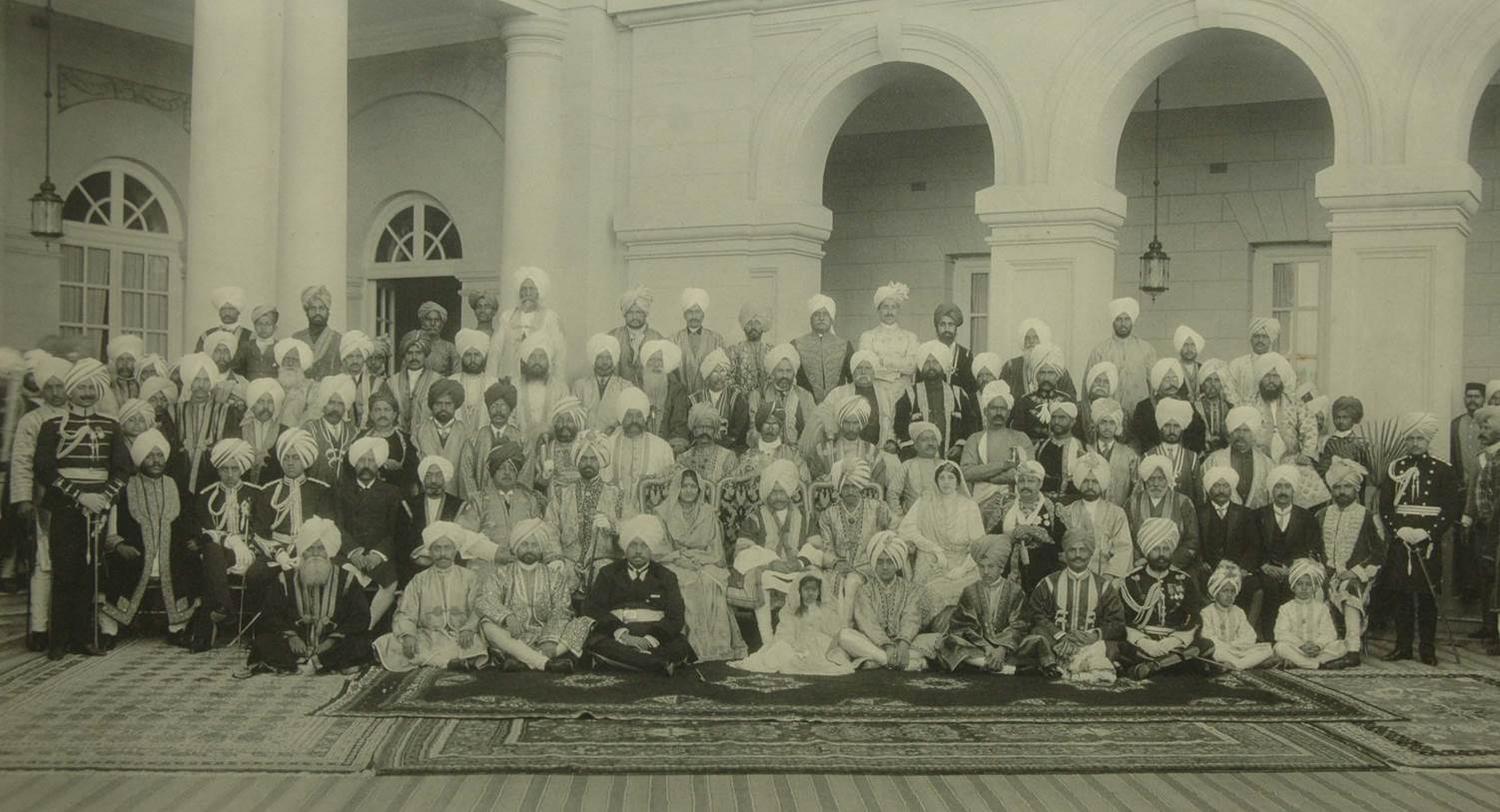

To give an example, during my research at the Foundation, I found several wedding albums, and I compared the 1911 official state wedding album of the Maharaja of Kapurthala (photographed by the famous Bourne and Shepherd Studio) to the 1921 scrap wedding album of the Rani of Mandi.6 I was drawn to the figures of the French-educated Rani Brinda and Anita Delgado of Spanish origins who clearly did not quite fit the visual norm of the family group photograph. Research revealed that the former did not yield an heir to the throne, and the latter got divorced, tentatively explaining their visual displacement. Yet I could only read into the contentious positions of these princesses by historicizing a social milieu that was modernizing in ways contrary to what they were familiar with in Europe. I found myself mapping a larger national history onto the fact that their photographs were removed from the albums. There were also glaring dissimilarities between the projections of the Kapurthala state souvenir album and the private memories embedded in the Mandi scrap album which awaits a more affectively sensitive study of official versus personal family photographic portrayals of royalty intended for different audiences. The personae of the two princesses as women of wealth, education, and culture were emblazoned on their bejeweled bodies that posed for the camera, yet my readings remained incomplete beyond what the archival status of these albums was able to reveal (see Fig. 9 and Fig. 10 in Hyperimage).

A niche between the institutional photographic archive and a family’s collection is occupied by the Indian Memory Project, described as “an attempt to trace a history of India, its people, professions, development, traditions, cultures, settlements and cities through pictures found in personal family albums and archives.”7 This online project initiated by Anusha Yadav, a professional photographer, seeks to virtually document pre-1990s family photographs as shared by their current guardians and owners. Images can be submitted to the site manager with details such as dates, names, locations, and professions of the subjects, who must be people of the Indian subcontinent. Their importance, the event, and historical value should all be explained by accompanying text.

The purpose here is not wholly academic, with the contents of the web page openly available to everyone, in line with practices of sharing personal data through online social networking methods such as blogging, Facebook, and Instagram. The photographs and texts sent by people from across the world are scanned by the moderator and uploaded, expressing narratives in the first person. This archive’s logic rests on the trust it instills in the family as bearer of truthful narratives behind photographs. Anusha says “this is the maximum validation and information one can ever get. No one knows better than family, and we trust that they are being factual and truthful.”8 Anusha’s confidence is of course questionable, as the mnemonic functions of family photographs have always been contingent on their owner/narrator, mutating across generations, homes, and intentions.

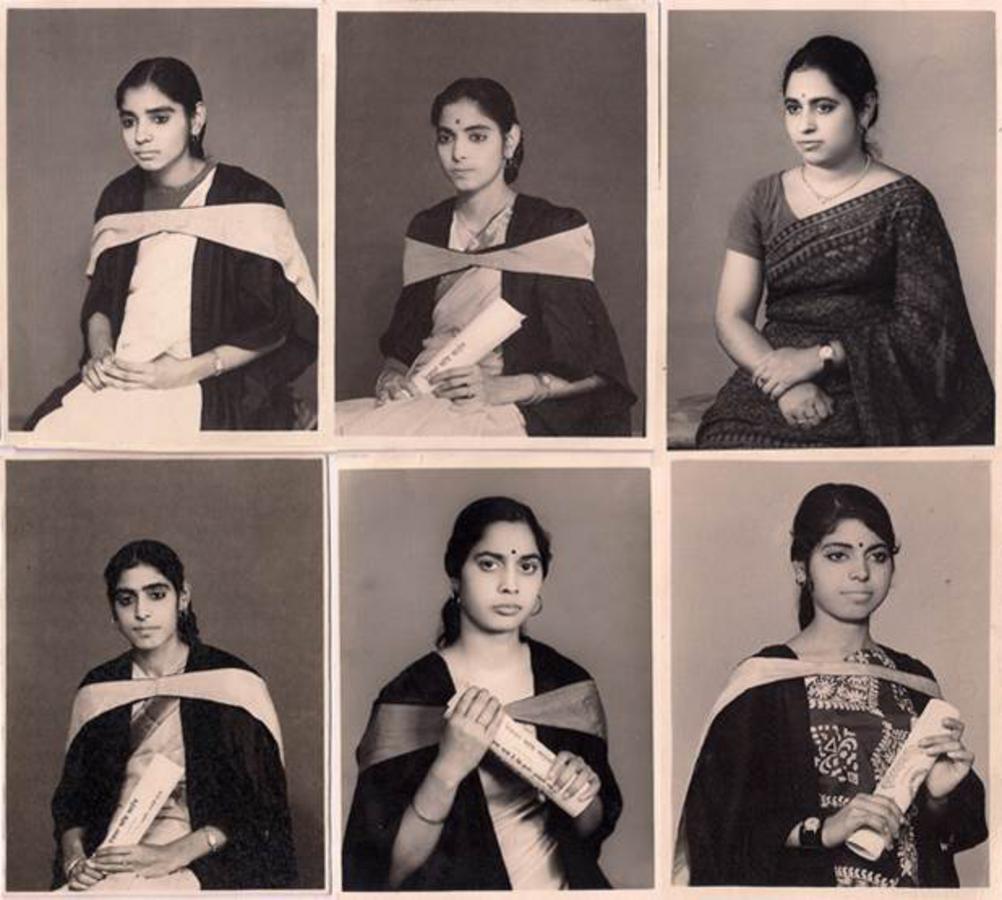

The Indian Memory Project’s overall effort to identify people, narrate their stories and their larger cultural milieu spills beyond the frames of the photographs. Some people prefer to show and tell about relatives posing with famous people, recognizable for their star quality. Others share intimate images of loved ones or unseen historic images that mark personal and familial change. Yadav writes on a series of photographs of her own mother and five aunts posing in identically sized studio portraits,

this is a collective image of my mother and her sisters, photographed holding their degrees with pride, between 1961 and 1971, as it was the custom at the time for women to be photographed to prove that they were educated. Some of these images were also then used as matrimonial pictures.9

She goes on to reveal how one sister died under mysterious circumstances, another eloped, and how education and domestic skills were highly prized assets. Family photographs and feminine narratives have a unique affiliation in the larger scheme of historical documentation, even as this affiliation is based on an oral-visual method rather than a textual one. Matrimonial portraits define a particularly important moment in the lives of Indian women who undergo arranged marriages, and the use of graduation photographs for the purpose of marriage complicates the contradictory nature of demands that modernity poses on the feminine figure. Through microhistories revealed in the Indian Memory Project, readings of the nation at various points in time are made possible, the visual not only substantiating but initiating investigation into pockets of interest (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: My mother Shalini (center, bottom row) and her five sisters Kusum, Madhavi, Suman, Aruna, and Nalini, unknown photographer, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, 1961–1971, courtesy of Anusha Yadav, Indian Memory Project.

6.2 Archives in motion

To contrast the institutional archive’s frameworks that, in the above progression of examples, seem to gradually expand one’s grip on historical exactitude, giving ground to a greater affective presence of memory, I would like to look at extensions of the photographic family archive in contemporary art practice in India. Dayanita Singh’s 2016 show called Museum Bhavan in Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art was unusual in that the photographer was also its curator, keeper, seller, and critic. This exhibition of a photographer’s own archive of images was organized not using walls, but wooden panels bearing grids with bars that held photos in their place. The structures were cleverly designed hybrids that could be collapsed or expanded as the artist wished, into suitcases, photo frames, shelves with reserve images, even furniture boxes, making the museum—and its meanings—mobile. The images were constantly on the move, changing places with other images by a logic internal to the artist, so that no arrangement remained the same on any two days. Each panel formed a “museum” titled by Dayanita, so there was the Museum of Little Ladies, the Museum of Chairs, the Museum of Love, the Museum of Men, the Museum of Chance, among others. The family finds shape in the relationships that Dayanita attributes to her museums. With herself as the “mother,” they become each other’s cousins, parents and siblings, confidants, friends, and witnesses (see Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Gallery view of the exhibition Museum Bhavan, courtesy of Dayanita Singh, 2015.

Fig. 13

Moving walls—Tetris-like image blocks in motion—clicking into place and making space for each other, encircling, expanding, and receding, make Museum Bhavan an archive in motion, a theatrical drama where relationships can knit themselves, travel, and unravel freely. For the artist, her images speak to each other and to the viewer in perceptible tones—making titles unnecessary. Visiting Museum Bhavan is an inversion of the usual exhibitionary experience, challenging what a museum or an archive has meant all this while. One cannot absorb Museum Bhavan simply by scanning its member images from a single point; there is no such flatness to it. Instead, one has to enter it, weave one’s way through it, get lost in it, and then find one’s way out. Through a lifetime of work, the artist has found the conventional catalog limiting, the titles of photographs constrictive, curators indifferent, archives rigid. The physicality of Museum Bhavan makes it a complete sensorial experience, unexpectedly going beyond the visual—with the artist even making “conversation chambers” for visitors enclosed within panel walls. Here, we may talk to chairs and machines, gaze at beautiful women from Bombay society, or respond to the questions that beseeching gazes of children bear.

Museum Bhavan is as much a comment on the archive as it is one itself. Its instability calls into question the idea of permanence that conventional archives embody. Its emotive content, uncontrollable spillages of meaning, and changing stories foreground affect as both an approach to understanding and a technique for presenting photographs. It remains for the viewer to make connections between an ascetic child from the ghats of Banaras looking at the portrait of the eunuch/transgender Mona Ahmed in her graveyard, as the latter dances to Zakir Husain’s throbbing tabla in another frame, and an empty bedroom yearns occupants to fill its spaces with the living. Dayanita’s photographic subjects are often well acquainted with her, and the photographs and their arrangements both reveal or conceal what she knows about them and their lives. Museum Bhavan remains a whimsical yet serious archive, one that may transform at will, as it also establishes undeniable connections between moments in the photographer’s own life as a witness to the world.

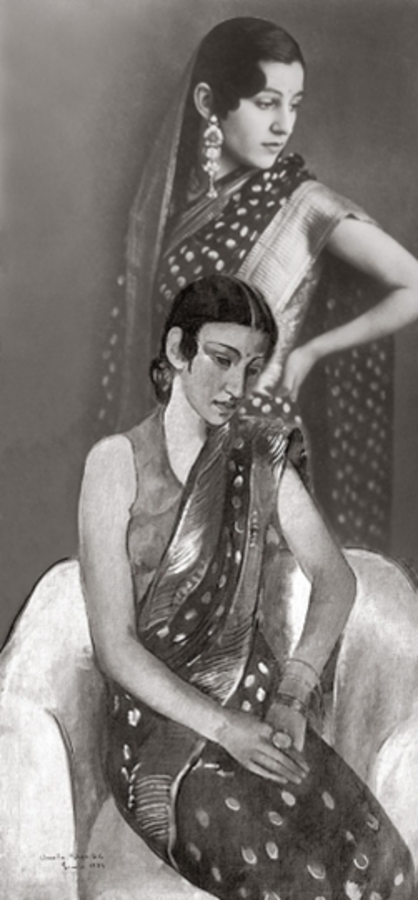

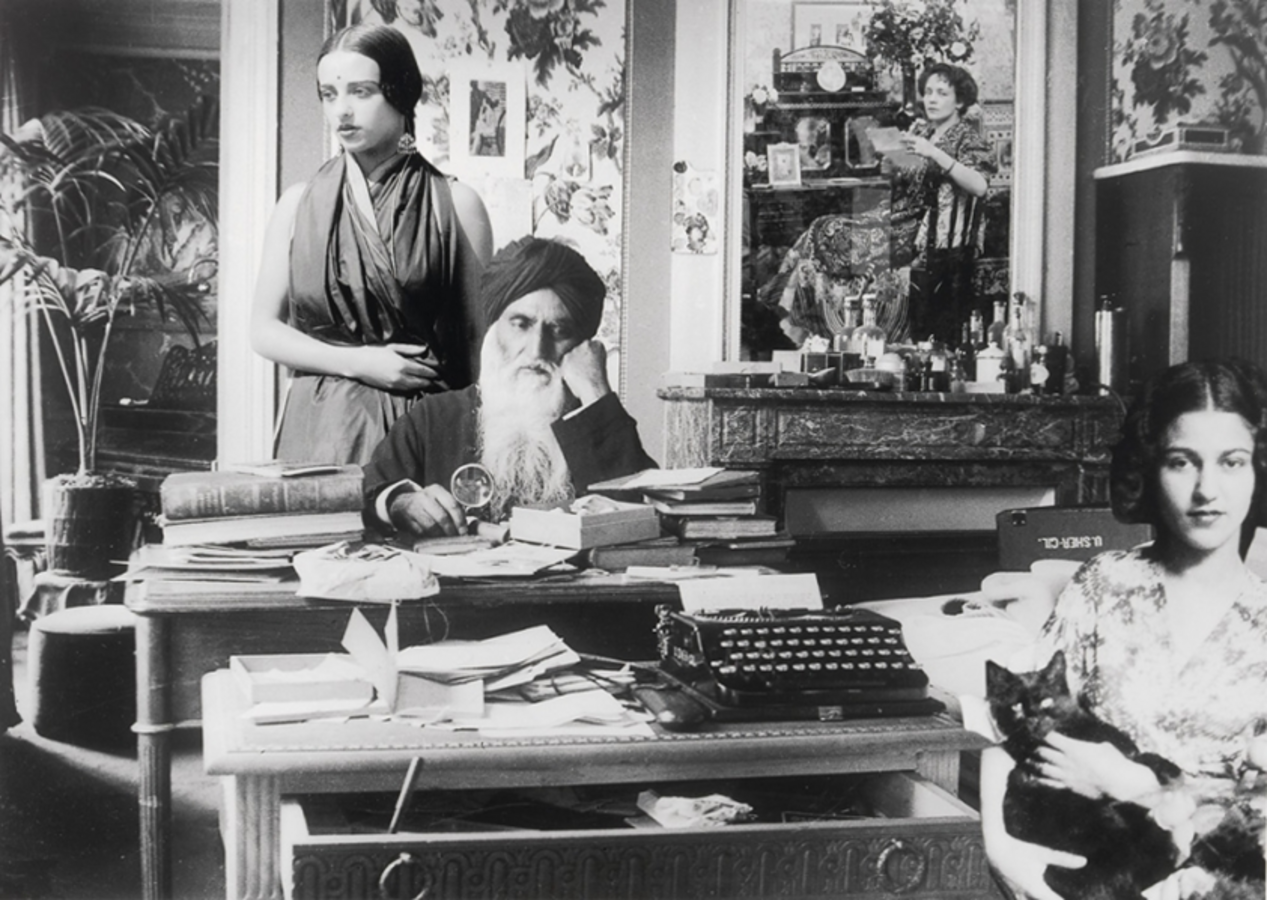

The artist Vivan Sundaram works with a substantial photographic archive of his maternal family. Vivan’s engagement with images of his famous aunt, the painter Amrita Sher-Gil whom he never met, or those of his own demure mother Indira and of his flamboyant grandfather Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, presents him several points of entry into a desired past. In his work titled Re-take of Amrita (2001), he moves as a participant interventionist into the history of his family, as someone both within and outside the memories embedded in the photographs, with legitimate access to reshuffle the fixity of the figures photographed. His engagement echoes the loving acts of collage making from personal scrapbooks and albums, repositioning figures and inventing backdrops to interweave memory with myth and retrospective desire. Photographic production here is more than a one-step process, as Sundaram intervenes to produce meanings in continuity, complementarity, and contestation to the ones originally intended. The artist attempts to read into personalities through these reconstructions. His grandfather Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, often appearing solo in carefully arranged gestures and settings is thus, “a highly self-conscious, obsessive, self-absorbed man who images his handsome body, his subjectivity, his being and his melancholy” (Sundaram 2008, viii).

With his “digital wand,” Sundaram plays with photographs, furthering the already performative personalities of Amrita and Umrao and the more introvert Indira into imagined scenes and conversations. He combines multiple photographs as well as Amrita Sher-Gil’s paintings into a series, proposing a narrative that would perhaps uncover hidden truths. Sundaram’s archive dwells in the realm of fantasy, as much as it knits together family montages in scenes of domestic intermingling. The multiple use of mirrors and the doubling of figures further puts to question the stasis of past personal relationships that we come to currently accept. Amrita, now dressed in a sari, admires her reflection only to have herself looking back in a western suit, visually contemplating but also displaying her identity as a person from two continents. Digitally maneuvered, her mother, Marie Antoinette, appears at the piano, her nephew—Vivan himself—in Umrao’s arms, the sisters smiling next to each other, creating a scene that completely skews all sense of chronology that the world knows of the Sher-Gil family. It is as if, on the inside, families never really are what they seem on the outside (see Fig. 13 in Hyperimage and Figs. 14–16).

Fig. 14: Self-portrait of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil at his study table, c.1933, glass plate negative, Vivan and Naveena Sundaram Collection, New Delhi, copyright: Vivan and Naveena Sundaram.

Fig. 15: Remembering the past, looking to the future, from the series Re-take of Amrita by Vivan Sundaram [Umrao Singh, Paris, early 1930s; Amrita, Bombay, 1936, photo, Karl Khandalavala; Marie Antoinette, Lahore, 1912; Indira, Paris, 1931]; digital photomontage, 38.1 x 53.3 cm, 2001, copyright: Vivan Sundaram.

Fig. 16: Bourgeois family: Mirror frieze, from the series Re-take of Amrita, by Vivan Sundaram [from left: Indira, Paris, 1930; Umrao Singh and Vivan, Simla, 1946; Marie Antoinette, Lahore, 1912; Small earring, 1893, Georg Hendrik Breitner; Amrita, Simla, 1937; Amrita, Budapest, 1938, photo, Victor Egan], digital photomontage, 38.1 x 66 cm, 2001, copyright: Vivan Sundaram.

In conclusion, the photographic archive attempts to position itself as the keystone against erosion of memory and material in time. It addresses what Geoffrey Batchen calls “an impossible desire: the desire to remember and to be remembered” even as photographs themselves “remind us that memorialization has little to do with recalling the past; it is always about looking ahead toward that terrible, imagined, vacant future in which we ourselves will have been forgotten” (Batchen 2004, 98). The photograph cannot thus guarantee remembrance, for it is the archive that must do this job. Yet, as I have shown, the relocation of photographs erases part of their meaning as their context transforms, some images carrying over their histories, while others are stripped bare, still others waiting to discover new stories, new interconnections, indeed, new family in the archive. The past always keeps in mind the future, something that separates it from the family album which is intended to preserve a certain version of the past. The archive must be able to not only organize what it presently has but also be capable of gathering more photographs: to allow a variety of sequences to make meaning, accommodate debate and dialogue between its many members that may sometimes end in surprising insights. The archive must challenge its own linearity or the sense of assumed completeness that a family album possesses, its categorizations and sequencing of images subscribing to a history that is external to, yet not exclusive of, ties of kinship. Like the ever-expanding population of India, family photographs and their residences will hopefully reveal new truths or confirm well-loved myths in their growing complexity. Yet the tensions of loss and gain of information will never settle, always leaving the image incomplete of its full potential to convey meaning. It is only the acknowledgement of the parallel existence of the institutional archive, the virtual voluntary collection, the digitized or material-based archive, artistic interpretations, and the many, many family collections that enables a well-rounded photographic understanding of India’s people.

6.3 Postscript

The conference Photo-Objects: On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences importantly identified the diversity of photographic archives from across the world. Each institution was shaped by the local characteristic features of its politics, cultures of collecting, image making, and ideas of preservation. This wide range of image repositories leads one to conclude that the archival impulse is universal; its intentions and constraints have no modular resolution for photographic classification, in either physical or ideological terms. From the examples above, it is clear that even internally, the Indian situation does not settle at a single, resolved definition of how images must be ordered, documented, or preserved, spawning many ways of archiving, and hence understanding, photographs. Importantly, these variations are inflected with the affective power of the familial, which subsumes meanings in a foremost sense. The absence of the family “orphans,” the image of its completeness, and the presence of the family creates a conundrum of meanings, difficult to contain within the archive. Ultimately, the unfulfilled desire embedded within the family album is for the resurrection of time and bodies, the lives of those whose eyes interlock our gazes with theirs.

6.4 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Subhamita Chaudhuri, from the film Family Album, directed by Nishtha Jain, 2011.

• Fig. 2 (in Hyperimage only): Subhamita Chaudhuri, looking through a stereoscope, from the film Family Album, directed by Nishtha Jain, 2011.

• Fig. 3 (in Hyperimage only): Chobi Ghosh, from the film Family Album, directed by Nishtha Jain, 2011.

• Fig. 4 (in Hyperimage only): Shelly Deb of the Nabakrishna Deb family, from the film Family Album, directed by Nishtha Jain, 2011.

• Fig. 5: Hardikbrata Biswasand Samita Sen, in conversation about the archive Family Album, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, still, https://youtu.be/jBIhmLcssEc, accessed January 21, 2014.

• Fig. 6: The Hitesranjan Sanyal Archives, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, courtesy of Ritwika Misra, 2017.

• Fig. 7: Portrait of Siddhartha Ghosh, late twentieth century, courtesy of Sanjeet Chouwdhury and the Hiteshranjan Sanyal Archives, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta.

• Fig. 8: View of the storage and archival research at the Alkazi Foundation, http://www.cssscal.org, accessed December 11, 2016.

• Fig. 9 (in Hyperimage only): Indian Wedding Guests from the wedding album of Sri Tikka Paramjit Singh of Kapurthala with Princess Brinda of Jubbal, Bourne and Shepherd [attributed], platinum print, 1911, 20.1 x 36.5 cm, ACP: 98.57.0001(3) Alkazi Collection of Photography.

• Fig. 10 (in Hyperimage only): Maharani Brinda Devi from HH Maharani Madalasa of Sirmur’s scrap album, G. L. Manuel Freres, gelatin silver print, 1912–1933, 19.3 x 13.5 cm, ACP: D2008.07.0005-00037, Alkazi Collection of Photography.

• Fig. 11: My mother Shalini (center, bottom row) and her five sisters Kusum, Madhavi, Suman, Aruna, and Nalini, unknown photographer, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, 1961–1971, courtesy of Anusha Yadav, Indian Memory Project.

• Fig. 12: Gallery view of the exhibition Museum Bhavan, courtesy of Dayanita Singh, 2015.

• Fig. 13 (in Hyperimage only): Style, from the series Re-take of Amrita by Vivan Sundaram [Indira, Simla, 1937; portrait of sister, 1936, by Amrita Sher-Gil], digital photomontage, 55.9 x 25.9 cm, 2001.

• Fig. 14: Self-portrait of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil at his study table, c.1933, glass plate negative, Vivan and Naveena Sundaram Collection, New Delhi, copyright: Vivan and Naveena Sundaram.

• Fig. 15: Remembering the past, looking to the future, from the series Re-take of Amrita by Vivan Sundaram [Umrao Singh, Paris, early 1930s; Amrita, Bombay, 1936, photo, Karl Khandalavala; Marie Antoinette, Lahore, 1912; Indira, Paris, 1931]; digital photomontage, 38.1 x 53.3 cm, 2001, copyright: Vivan Sundaram.

• Fig. 16: Bourgeois family: mirror frieze, from the series Re-take of Amrita, by Vivan Sundaram [from left: Indira, Paris, 1930; Umrao Singh and Vivan, Simla, 1946; Marie Antoinette, Lahore, 1912; small earring, 1893, Georg Hendrik Breitner; Amrita, Simla, 1937; Amrita, Budapest, 1938, photo, Victor Egan], digital photomontage, 38.1 x 66 cm, 2001, copyright: Vivan Sundaram.

6.5 References

Batchen, Geoffrey (2004). Forget Me Not. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati (2011). The City in the Archive: Calcutta’s Visual Histories. Calcutta: Seagull Arts, Media Resource Centre, and the Ford Foundation.

Hirsch, Marianne (1997). Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Post Memory. Harvard University Press.

Karlekar, Malavika (2005). Re-Visioning the Past: Early Photography in Bengal 1875–1915. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Samita, Ranjita Biswas, and Nandita Dhawan, eds. (2011). Intimate Others: Marriage and Sexualities in India. Calcutta: School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University and Stree Publications.

Sundaram, Vivan (2008). Forward. In: His Misery and His Manuscript. Ed. by Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. New Delhi: Photoink, viii.

Tola, Chhobi (1988). Bangalir Photography Charcha. Ananda.

Footnotes

Subhamita Chaudhuri in the film Family Album by Nishtha Jain, produced by Raintree Films, India, 66 minutes, 2011.

From the web page of the India Foundation for the Arts, http://www.indiaifa.org/school-women%E2%80%99s-studies-jadavpur-university.html, accessed December 10, 2016.

From the web page of the Hitesranjan Sanyal Memorial Archive, http://www.cssscal.org/archive.php, accessed December 11, 2016.

This can be translated as follows: "Taking Photographs: A Discussion on Bengali Photographic Practice."

The 1911 album documents the wedding of Maharaja Jagatjit Singh of Kapurthala’s eldest son and heir to the throne Prince Paramjit Singh to Princess Brinda of Jubbal, while the second album is the personal scrap album of the wedding of Rani Amrit Kaur of Kapurthala, daughter of Jagatjit Singh, married to the Raja of Mandi Joginder Sen Bahadur. Maharaja Jagatjit Singh’s affectation for all things French made him educate Rani Brinda in France for five years before she married his eldest son Raja Paramjit Singh. Anita Delgado, a Spanish dancer he met during the wedding of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, also received an education in Paris for several months before he took her as his wife and brought her to Kapurthala.

From the web page of Indian Memory Project: About, https://www.indianmemoryproject.com/about/, accessed December 10, 2016.

Author’s interview with Anusha Yadav, Mumbai, 2012.

From the web page of Indian Memory Project: Six triple degree holding sisters of Agra, https://www.indianmemoryproject.com/50/, accessed December 10, 2016.