From outsized albums to stapled contact prints on forms, the entry of photographs into cataloging has often been one of mechanical compromise as the photographic materials were incorporated into the older and venerated textual surround of the catalog. In this essay on the materiality of photographic catalogs, the physical repository of image substance and written or typed notation bears scrutiny as a carrier of important information both about the collection and about the status of the image as a bearer of important information. Catalogs of all sorts have long been a target for scholars of bureaucratic and museum studies. Geoffrey Swinney in particular has excavated registration practices in museums (Swinney 2012). This paper addresses the introduction of photography into text-based catalogs, both in museums and in the commercial world, as a significant change in the materiality of cataloging. Between the unwieldy mechanical compromises of the late nineteenth century and the apparently seamless collaboration of digital catalogues of the twenty-first century, the separate material cultures of word and image are interrogated to clarify the changing nature of knowledge hierarchies in photographic catalogs.

Analog photographic catalogs are products of the back room. In often makeshift darkrooms, under the red glow of safe lights, amidst the fixer fumes—roller processors, fed by the photographer, spat out almost unimaginable thousands of catalog photographs. These photographs made their way inexorably toward their home deep within museum protocol, where they nested in the bureaucratic framework of the museum catalog. Part of what they took with them was the trace of the embodied work of the copy photographer, or the museum photographer. In that numbingly repetitious and precisely organized workflow, exposure, development, fixing, and washing to archival standards are all part and parcel of keeping the ravages of time at bay, photographically speaking. The physicality of such photographs is undeniable because they are part of a photographer’s workflow. Yes, they all look the same (but do they?) and yes, they are deeply boring (but are they?). I began to query that sentiment. How could something so redolent of the material practices of photography ever be harnessed to something as textual as a catalog? In this paper, I consider some ways in which I think it happened and what some of the consequences might be.

First, though, I should address the first part of my title, that is, the two cultures of word and image. Like art and science, words and images have long been set at odds in a type of present-day culture war. It began perhaps in the “October Moment” of the 1970s, and comes from authors like Rosalind Krauss1 setting words and images at odds with one another at opposite ends of the spectrum—never to meet in any kind of coherent or productive working space. Many of us publicly lament the hierarchy of historical sources that often leads to photographs becoming mere illustrations to that “main event,” the history text.2 There is also another way to look at the relationship between text and image. In her article “Scientific Objectivity Without Words,” Lorraine Daston distinguished communitarian objectivity as an objectivity that “cultivated language” as different from mechanical objectivity which “rejected language,” preferring the directness of nature itself (Daston 2004, 262–263).

That is, the artifice of text is countered by the directness of nature and the natural qualities of the photograph. Not only have numerous scholars asserted the photograph’s reliance on text to clarify or anchor meaning, but photographic historians have often argued (and I count myself among them) for the thickening of historical accounts through the use of photographs, and not just text. The just implies perhaps an unhelpful dichotomy. Recently, in Photographs, Museums, Collections, Elizabeth Edwards and Chris Morton suggested another model by which we might consider the coming together of words and text. They claimed that texts and images in museums were “mutually generative” (Edwards and Morton 2015, 17). This immediately resonated, as I have been deeply (perhaps obsessively) interested lately in catalogs. The digital catalog seems to epitomize such mutually generative processes of image and text working together and not in opposition to create something new.

Of all the documentation that occurs in museums, what is so special about catalogs? Catalogs are the interface of retrieval between the collection, or archive or library, and the user. They consist of documentation, but also of discoverability.3 “Catalog” is also a word, and a physical thing, that is deeply connected with sales. This connection to the outside world, and to commerce is what particularly interests me today, although I won’t deny that documentation is in itself a seductive and critical topic of conversation. For the purposes of this paper, I have focused on the time when catalogs became photo-objects, moving irretrievably from solely text-based objects to photographic objects, or, “mutually generated” objects. To be very crude about it, and to make some distinction for shortening this paper, I have decided not to deal with text-only catalogs, about which much as been written, or with digital catalogs, about which much is being written, in order to concentrate on the space in between, when photographs were first introduced into and as catalogs in often awkward material ways. I do this not to be awkward, but because I think these first attempts, of analog photographic-text catalogs provide some good material to think with when it comes to photographic catalogs.

The history of this paper began ten years ago, when the conflict between photographs and catalogs first impeded one of my own research queries. In the Science Museum, London, where I was looking for scientific photographs that had not yet been digitized, it proved impossible to find photographs. That is, it proved impossible to find the photographs I thought of as my research target because most things in the museum store had at one time been photographed and the term “photograph” appeared in the metadata of all records. At the time, it was an annoying but circumventable problem, and in some ways no more than a material incarnation of Malraux’s or, more recently, Preziosi’s remarks about whole fields of history or art history being subsumed into photography.4 On reflection, it raised some important questions about the nature of science photography archives, which I addressed in Florence in 2009 at the Photographic Archives I conference (Wilder 2011). In that essay, I mentioned this encounter and promised that a consideration of the implications for photographs would be the topic of another paper. Slow as it was in coming, this is that further paper.

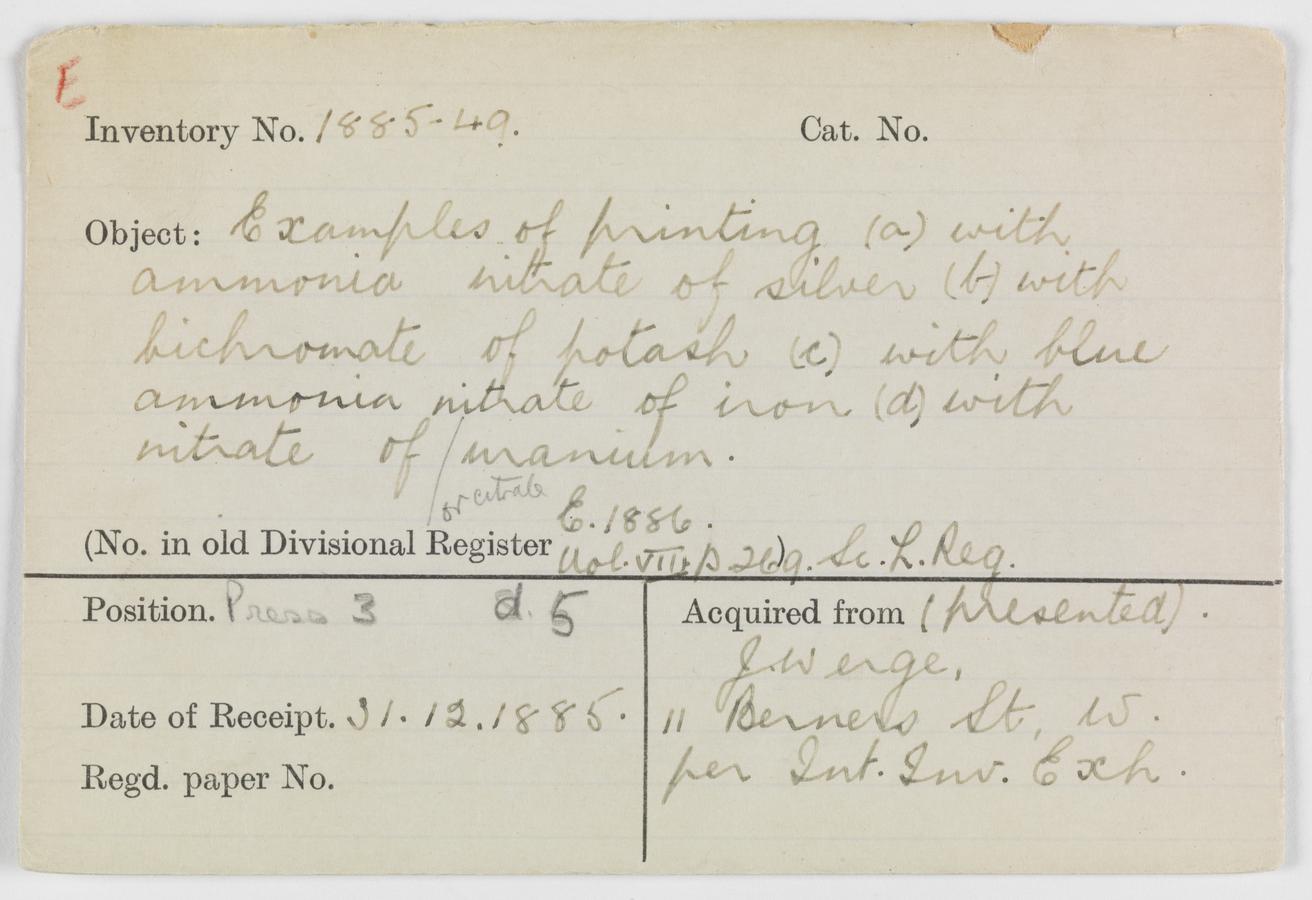

Let us consider a catalog. A catalog card (see Fig. 1), standard 3x5 inch size, inventory number 1885-49, describes the object as follows:

Examples of printing (a) with ammonia nitrate of silver (b) with bichromate of potash (e) with blue ammonia nitrate of iron (d) with nitrate (and there is a small aside in pencil here saying ‘or citrate’) of uranium.

It has another number, vol. 7, p. 269 of the Science Library Register. I take the E. 1886 to mean that it was exhibited in 1886.5 The object was acquired from J. Werge late in December of 1885. J. Werge is John Werge, a notable Scottish daguerreotypist and experimenter. It says “for the Int. Inv. Exh.,” quite likely the International Exhibition of Industry, Science and Art held in Edinburgh in 1886 (about which we know almost nothing of the photographic contributions to the exhibition).

Fig. 1: Form 100, John Werge, Examples of Printing, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

This is the Form 100 card used by the Science Museum, London for many years. When much of the photographic collection moved to Bradford to form the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television (now the National Science and Media Museum), the catalog moved with it, or part of the catalog did, the part that pertained to objects going to Bradford. As such, it constituted the first catalog of a new national museum of photography.

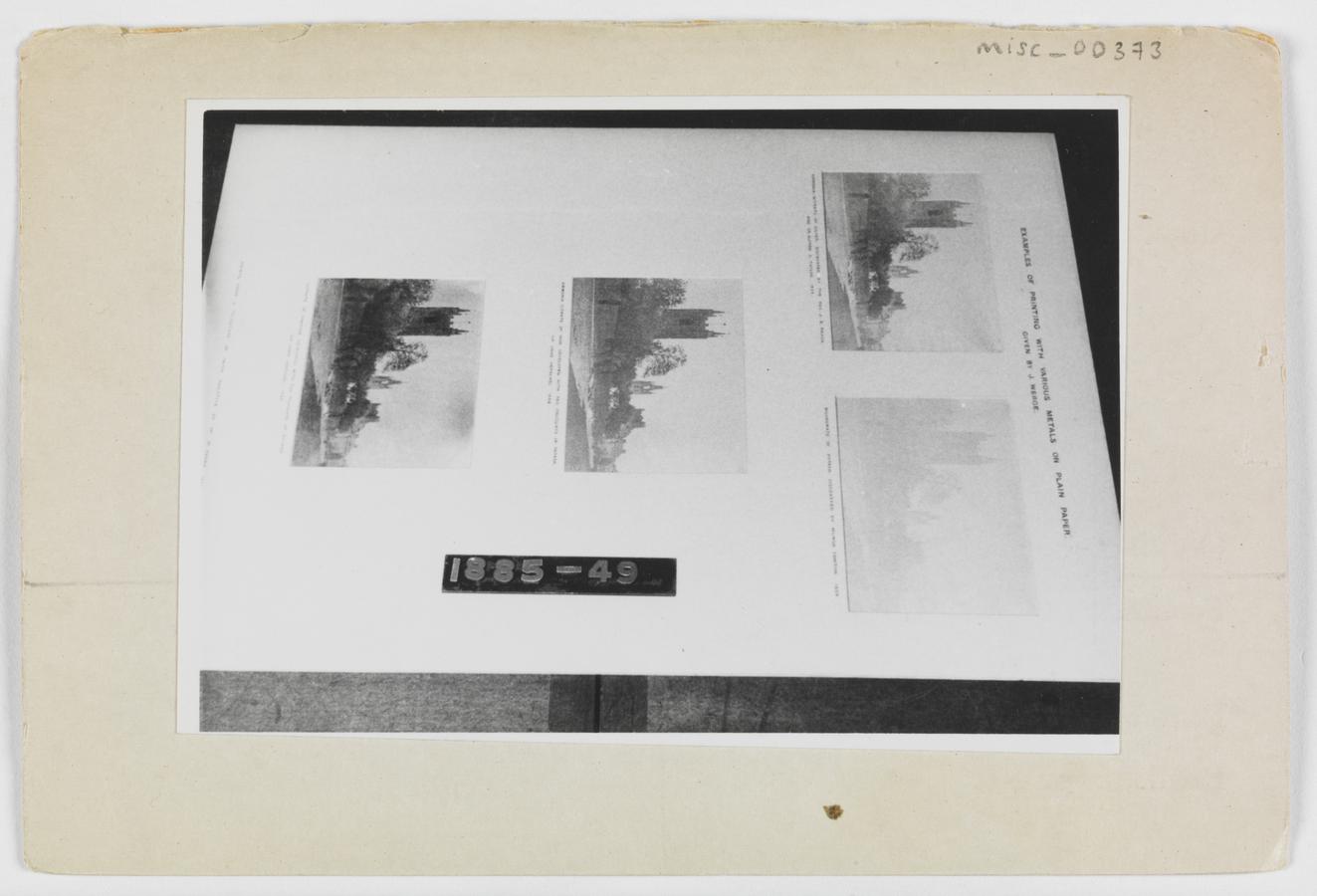

On the back of the card (see Fig. 2), there is a photograph and a further number, “misc 00292.” “Miscellaneous” is a word that photographs are filed under so frequently we really need a thorough investigation of it. The photograph on the back is a twentieth century black and white gelatin silver print, glued on, showing a board with four mounted photographs and a number, 1885-49, corresponding to the inventory number on the front. This is a really curious photograph. It’s not a copy photograph in the professional sense. That is, it is clearly not taken on a copy stand, with even lighting either side. Although these details may seem insignificant, it brings the act of photographing museum objects very much to the fore. There is no pretense of transparency in this photograph. It is so clearly photographic, in the oblique angling of the board and the cropping of the two front corners. They bring to light the edges of the photograph and the photographic process. It embodies the viewer, placing him or her in the correct place to photograph this object. It is also clear what is considered to be “important” here, namely the inventory number. The captions under the photographs are illegible. Size is not indicated. The monochromatic photograph elides any color information. The only clearly legible part of the photograph is the number. But the number is already listed on the front, begging the question, what is this photograph for? While the board and its photographs are not wildly three-dimensional, this photograph of the photographs gives them much more three-dimensionality; in short, they are photographed like an object. So here is a photo-object within (or rather pasted on) a photo-object.

Fig. 2: Form 100, verso showing photograph of Werge, Examples of Printing, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

We should think about the timing of copying photographs in relation to the other events in the institution’s life, as Morton and Edwards, and Joan Schwartz urge us to do.6 Thinking about the “why?” and “what for?” of this photograph on the back of a catalog card, we might be able to draw some conclusions. The museum objects (or object) were (was) donated in 1885. The copy photograph is not made with technology from 1885, but with mid-twentieth century resin-coated paper. Resin coating was introduced to photographic papers in the 1970s, so we can safely say that the photograph entered the text-based catalog within a decade of the founding of the National Museum (Stulik and Kaplan 2013). I’m going to go out on a limb and argue that the objects were very likely photographed as a part of the impending move from one part of the Science Museum Group to another—from London to Bradford. But not all Form 100s have photographs attached to them. There seems to be no apparent strategy to the photographic “campaign” but the photographs are all a similar size and of a similar, shall we say, ad hoc, nature. Is this a “photographic statement” in Allan Sekula’s linguistic sense?7 I don’t think it is.

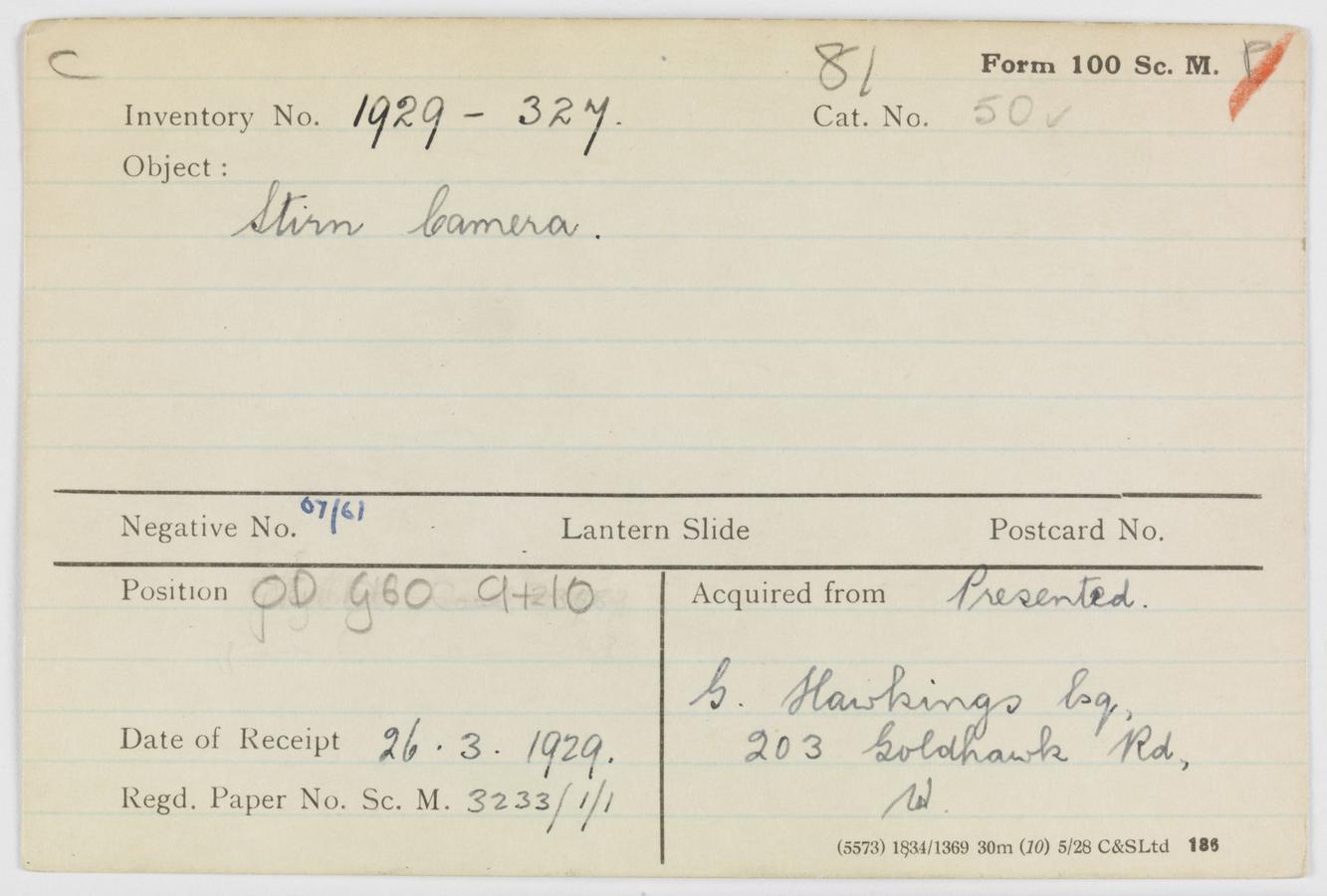

Take this one other example of a Form 100, inventory number 1929-327, a Stirn camera (see Fig. 3). In this Form 100, a slightly later version, photography has already changed the nature of the text on the front. In the middle is a printed band that asks for the negative number, lantern slide, or postcard. This information is not provided on the first Form 100. The earlier version of Form 100 has no place for photography; the photograph is on the back. The later form has a place for registering numbers of photographs. It is already acknowledging in some official way, Elizabeth Edwards’ “non-collections” that are not really acknowledged. They have been given numbers but are not acknowledged as collections. These sorts of notations can be found in many collections— sometimes as a small pencil mark next to a print, reading “negative.” The objects are virtually impossible to find, but traces remain everywhere.

Fig. 3: Form 100, Stirn camera, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

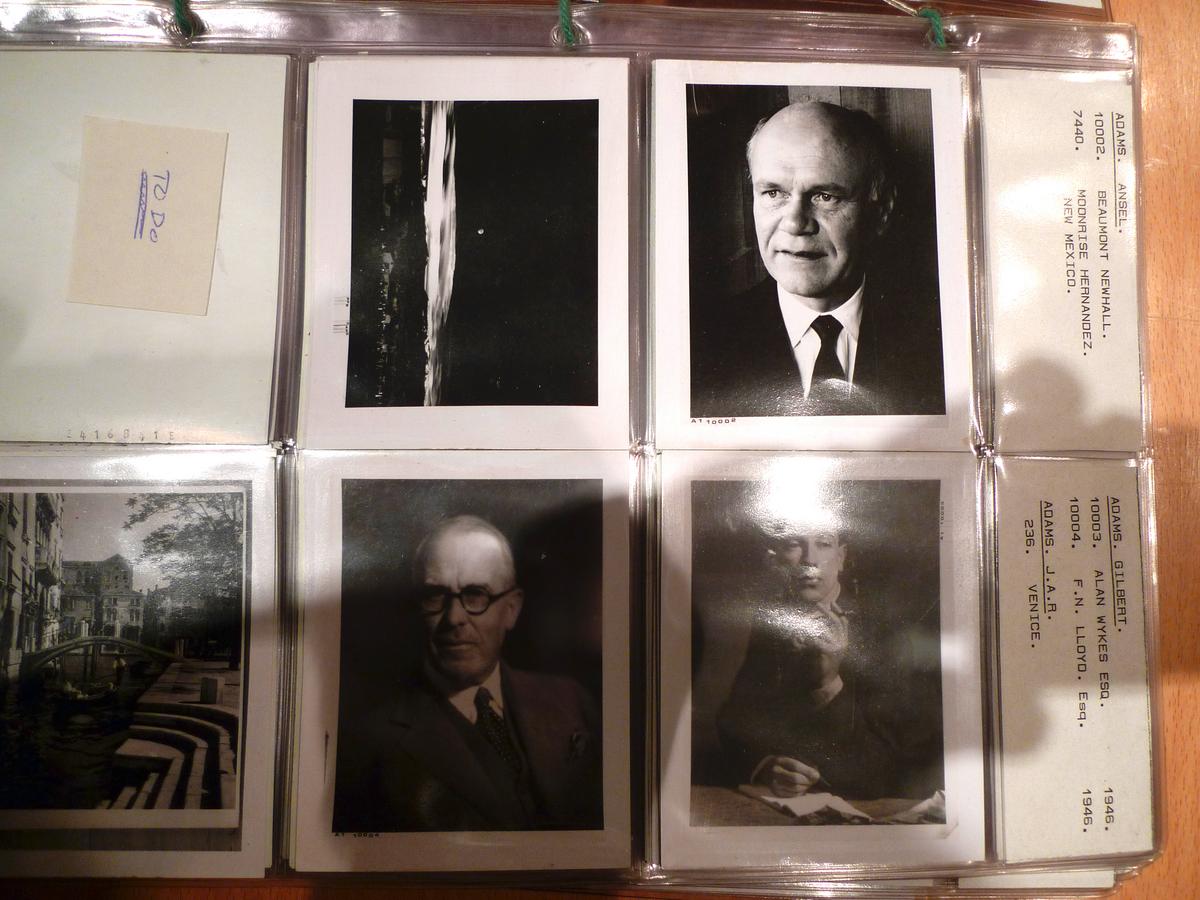

The photograph on the back of this later Form 100 card is even more curious (see Fig. 4). It is roughly the same size and shape as the previous photograph— but it was trimmed unevenly, apparently to get rid of as much of the curator’s arm as possible without cropping out the object. But here what is so curious is the number of objects and how ambiguous it is as a photograph that should match the catalog entry. The catalog number and card say “Stirn camera” and the photograph shows the Stirn camera, but much more prominently, the inventory number (later corrected) and a slightly disheveled display contact print of a Stirn camera plate, with its six round exposures. It does not show a negative, but a contact print made from a negative. It also shows a caption that was apparently meant for display.

Fig. 4: Form 100, verso showing photograph of Stirn Camera and associated items, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

The photograph not only reproduces the object belonging to the inventory number but it also indicates associated material in the collection. That is, it suggests connections in the collection that the inventory number might or might not reflect. There are certainly textual ways of cross-referencing such information, but they are not evident here on the form. There are ways of cross-referencing it to other photographic processes within the museum for copying that object (lantern slides, negatives, and postcards), but only of that object, not of related objects. It is true that this inventory number is in fact related to not only that contact print but the negative plate as well, which has in the past been exhibited alongside the camera. The photograph on the back of the form suggests a natural grouping of objects belonging together—a curatorial selection—a bit like a small version of a family photograph.

So this is one way that photographs come to be in a catalog, pasted on the back, where they can’t be seen at the same time as the text. That is, a viewer can either look at the front or the back but not both at the same time, making haptics of looking at catalogs a critical point of interest. That is only one way in which photographs inserted themselves into the text of the catalog. They arrived and were added to the back of some convenient card in a haphazard way, adding an associative type of metadata. But this is not the only way photographs become catalogs.

There are more deliberate, organized ways of making catalogs. In 1975, the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) teamed up with Polaroid to copy its photographic collection of nearly 15,000 prints (see Fig. 5). Like many of these projects, the reasons for the outlay included three primary areas: cataloging, preservation, and commercial return. Using the famed MP4 copying system advertised by Polaroid, a single operator could (it was asserted by Polaroid) make up to 60 copies an hour. It would, at that rate, take a mere six months to copy all the prints in the RPS collection at the time, making not one, but two parallel catalogs. The insertion of photographic companies into the museum catalog in this way is not a novel one, and it was not new to the Royal Photographic Society. It was also not new as a sales tactic among the big photographic companies: Polaroid, Kodak, Agfa, and Ilford. Each had a proprietary copying system by which the company would try to guarantee reproducibility, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. None of these campaigns are cost effective but the companies did a very good job trying to sell the notion of it. In the Bradford collection, there is also a letter from Polaroid attempting to sell the museum just such a system. It was a concerted effort by Polaroid to insert itself into this quite lucrative industry of photographic archiving and cataloging.

Fig. 5: Royal Photographic Society polaroid photographic catalogue, RPS Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The two catalogs would be first, the set of MP4 negatives that would remain with the RPS, and second, the positives, which would go to the library, and be made available for reference (“Copying the Collection” 1975). The photographs were indexed using an alphanumeric system, and each number was photographed next to the photographic object it designates. The ensuing catalog of black and white polaroid prints were filed in plastic sleeves with a typed heading accompanying each page. The catalog proceeded in alphabetical order by photographer, beginning with Adams, A.

Fig. 6: Pots in a sales catalog, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

This is a photo-object that consists entirely of copy photographs. Each one of them is a photo-object but the whole catalog is also a photo-object. These copy photographs, made with a professional system for copying flat documents, does decidedly try to be transparent. These small Polaroids do all the things photography does best. They shrink, unify, and homogenize objects of different size, color, and shape in order to make them subject to a certain kind of delivery in the reading room. In the case of the RPS collection, it also allowed a reorganization of the “collection” for the user. Normally, the prints were housed according to size, and the size of the mount. With this photographic catalog, researchers could encounter not just the finding aid, but (it was hoped) the photographs in alphabetical order by photographer. The collection remained housed by size. Make no mistake as well, in a 1975 article about the copying campaign, it was made clear that these Polaroids were to be consulted in place of the prints in all cases.

The prints themselves, when the copying is completed, will only have to be brought out for the occasional exhibition... (“Copying the Collection” 1975)

This is often another driver behind the photographic catalog—the wholesale replacement of the original objects for the so-called “convenience” of the researcher and the “conservation” of the object. But there is a third and, I would argue, more pressing reason for the photographic catalog. It is inherently commercial. This was not an aspect that escaped the notice of the RPS.

…copies of any size can be produced from the Polaroid negatives by a high quality commercial trade house. The new system, with negatives already in stock, will be faster for the consumer and will produce higher returns for the Society. (“Copying the Collection” 1975)

If catalogs are interesting because they are the interface between the collection and the public, they are also interesting for the diverse use in both museum and commercial practice. The sales catalog had long become photographic by the time these two photographic catalogs were made. Fig. 6 shows a catalog from the first decades of the twentieth century presenting antique brass pots for sale. Each item here has a number, and a price, and the customer could “browse” virtually through the offerings of this company and order to suit their taste or pocketbook. The idea for photographic catalogs in the style of such a sample book is as old as 1839, when William Henry Fox Talbot tried to interest the lace manufacturers in photogenic drawings to take the place of lace samples. The notion that photography is out there to flog wares of one sort or another is an important notion for considering the interface of catalogs moving from the textual to the visual.

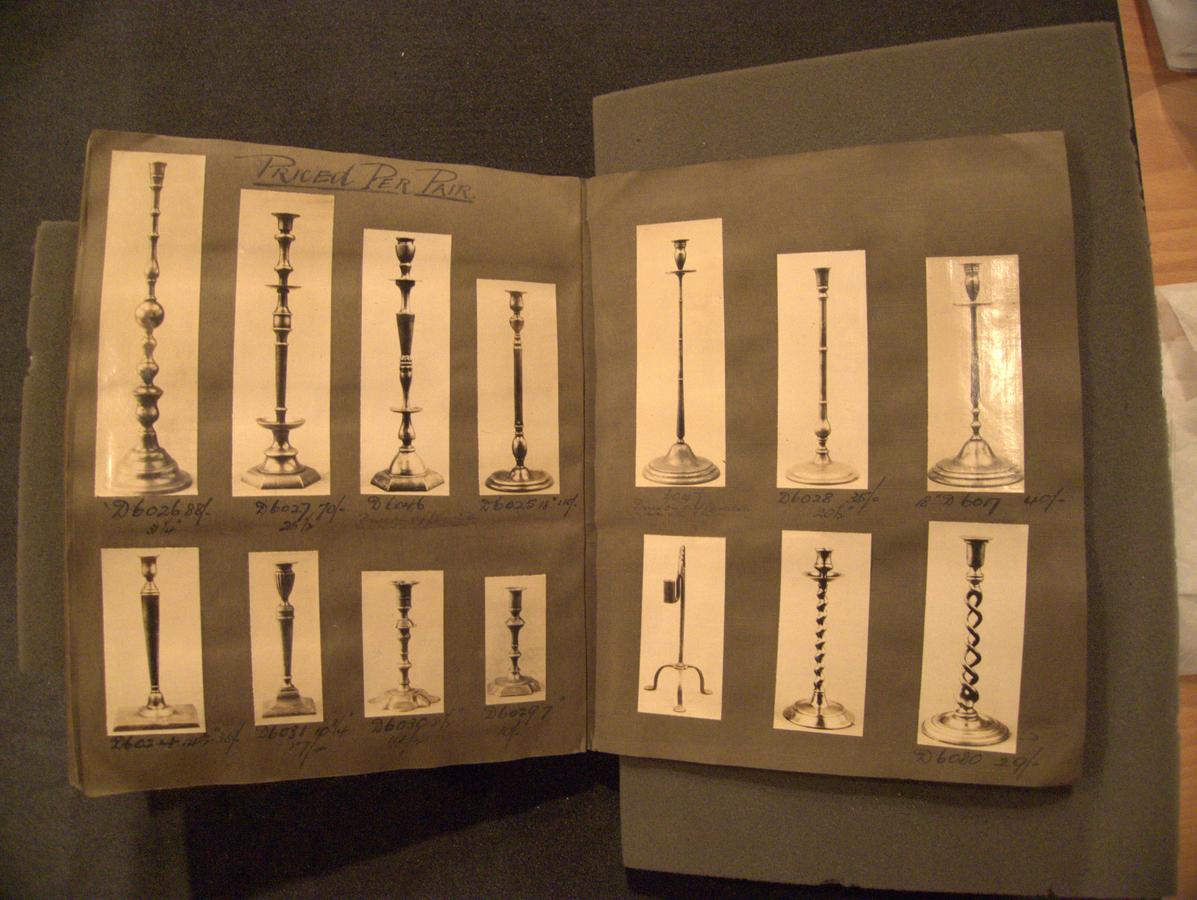

The sample book is a very old form of sales catalog and it was enthusiastically populated by photographs like candlesticks (see Fig. 7), and lantern slides, and tourist views.8 It will come to no surprise to those who work in museums to find the financial considerations close to the surface. It is, however, also true that we tend to talk about knowledge, epistemic values, and classification a lot when we discuss catalogs and this is a plea not to ignore the grubby subject of commerce in the increasingly visual nature of museum catalogs.

Fig. 7: Candlesticks in a sales catalog, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

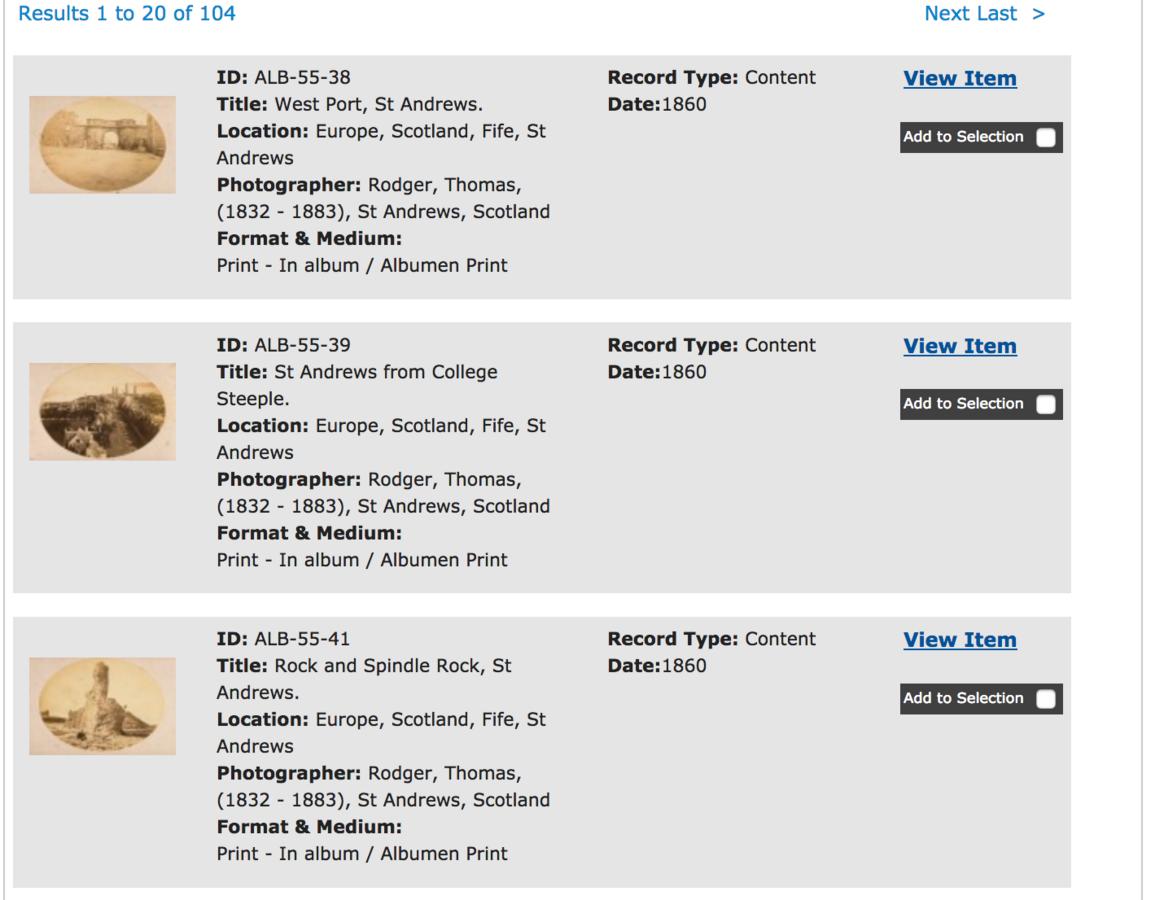

It has taken a relatively short time for catalogs to have merged the text and image not into an opposition but into a mutually generative set of photo-objects, where the image and text, as Elizabeth Edwards showed us on the first day of the conference with her disappearing caption, are constantly renegotiated in and around each other. They are harnessed together to do very specific things. The embodied work of the managers of digital catalogs (see Fig. 8), or digital assets as they are now called, has yet to be fully understood but no doubt they will come to be seen as the catalysts and agents of, in, and around these new forms of objects, which are increasingly naturalized, rather more fluid than fixed, and mutually generative in the cataloging workflow.

Fig. 8: Screenshot of digital Catalog, St. Andrews University Special Collections, photo: Kelley Wilder.

15.1 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Form 100, John Werge, Examples of Printing, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 2: Form 100, verso showing photograph of Werge, Examples of Printing, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 3: Form 100, Stirn camera, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 4: Form 100, verso showing photograph of Stirn Camera and associated items, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 5: Royal Photographic Society polaroid photographic catalogue, RPS Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

• Fig. 6: Pots in a sales catalog, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 7: Candlesticks in a sales catalog, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford.

• Fig. 8: Screenshot of digital Catalog, St. Andrews University Special Collections, photo: Kelley Wilder.

15.2 References

Caraffa, Costanza (2011). From Photo Libraries to Photo Archives: On the Epistemological Potential of Art-Historical Photo Collections. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin and Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 11–44.

Copying the Collection (1975). The Photographic Journal 115(7):308–310. url: https://archive.rps.org/archive/volume-115/745684 (visited on August 17, 2019).

Daston, Lorraine (2004). Scientific Objectivity with and without Words. In: Little Tools of Knowledge. Historical Essays on Academic and Bureaucratic Practices. Ed. by Peter Becker and William Clark. Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press, 259–284.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Christopher Morton (2015a). Between Art and Information: Towards a Collecting History of Photographs. In: Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. Ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton. London: Bloomsbury, 3–23.

– eds. (2015b). Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. London: Bloomsbury.

Schwartz, Joan M. (2012). ‘To Speak Again With a Full Distinct Voice’: Diplomatics, Archives, and Photographs. In: Archivi fotografici: spazi del sapere, luoghi della ricerca. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa and Tiziana Serena. Rome: Carocci Editore, 7–24.

– (2014). Photographic Records/Archives. In: Encyclopedia of Archival Concepts, Principles, and Practices. Ed. by Luciana Duranti and Pat Franks. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 270–274.

Sekula, Allan (2003). Reading an Archive: Photography Between Labour and Capital. In: The Photography Reader. Ed. by Liz Wells. London: Routledge, 443–452.

Stulik, Dusan and Art Kaplan (2013). Silver Gelatin. In: The Atlas of Analytic Signatures of Photographic Processes. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

Swinney, Geoffrey N. (2012). What Do We Know about What We Know?: The Museum ‘Register’ as Museum Object. In: The Thing about Museums: Objects and Experience, Representation and Contestation. Routledge: Routledge, 31–46.

Wilder, Kelley (2011). Locating the Photographic Archive of Science. In: Photo Archives and the Photographic Memory of Art History. Ed. by Costanza Caraffa. Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 369–378.

Footnotes

I am indebted to Elizabeth Edwards for this wonderfully accurate way of describing the use of images in history.

This might also consist in the discoverability of connections to other items, as in the Stirn camera.

For a discussion of these sentiments, see Caraffa 2011.

Werge exhibited the board, or one with the same description, before 1886. Exhibit 325 at the 25th RPS exhibition in 1880 found in Exhibitions of the Royal Photographic Society 1875-1915, shows us that this board may be the one depicted on the catalog card, or a sister example.

Edwards and Morton 2015b. Many of Joan Schwartz’s writings touch on the photograph in this way, particularly her work on diplomatics. See Schwartz 2014 and Schwartz 2012.

“In terms borrowed from linguistics, the archive constitutes the paradigm or iconic system from which photographic ‘statements’ are constructed” (Sekula 2003, 446).

See the Samplebook of photographer Thomas Rodger on the website of St. Andrews University, https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/imu/imu.php?request=display&port=45175&id=062a&flag=start&offset=0&count=10&listcount=20&view=list&irn=355567&departmentfilter=Special%20Collections&ecatalogue=on, accessed April 20, 2018.