In a catalog of “photographic treasures” published in 2016 by the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (IFAO), a double-page spread of black-and-white photographs, surrounded by the white page, placed a rough-textured, hand-modeled, raw clay face on the left page and on the right page, a front-facing portrait of an elderly bearded Egyptian man, his wrinkled face framed by the folds of a turban and scarf (Driaux and Arnette 2016, 144–45). Founded in Cairo in 1880, IFAO continues to sponsor excavations, and its photographic archives are approaching a half million negatives (Driaux and Arnette 2016, 2). The photographs of the raw clay object and the white-bearded man selected from those archives do not share a date, photographer, place taken, or physical format. Instead, they appear to have been paired based on formal similarities between the two faces they represent—one ceramic, one human. At the back of the book, the editors give the dimensions, media, and catalogue numbers of the negatives, and lament the lack of information otherwise available (Driaux and Arnette 2016, 301–2). On YouTube1, the book’s publication was announced with a short film soundtracked by vaguely North African- or Middle-Eastern-sounding music, by the same Australian performer (Lisa Gerrard) whose work featured in the film Gladiator.

Archaeological archives, and their millions of photographs, must be among the most substantial archives formed during the colonial era, yet neither the concept nor any critique of colonialism has managed to stick to them, as this example from IFAO’s recent archive-based project—however well-intended it was—makes clear. Archives, and perhaps photographic archives in particular, or most obviously, continue to be seen within archaeology (including Egyptology) as direct and unmediated sources of information about a site or an artefact, or as evocations of a golden age of archaeology in Egypt.

Given that archaeology is a discipline widely seen to have had its material turn, what makes “the archive” seem so immaterial, so inviolable—and so orientally alluring? Working with archives, or with a museum collection as I used to do, should quickly undermine any idea that objects and the archival practices associated with them can ever be distinct (Riggs 2014, 7–18; 2017). Both take material form, and both bear the mark—sometimes literally—of the colonial realities and imaginaries that made Egyptian archaeology possible. Archaeology’s resistance to seeing photographs as anything other than images or evidence may seem to be a function of photography’s famed indexicality and the two-dimensional ease of reproducing it (Bohrer 2011, 7–26). However, I argue that there is more at work here, and more at stake, and that this has to do with the endurance—the entrenching, to use an apt metaphor—of a disciplinary consciousness: that is, how ways of doing, thinking, and seeing replicate themselves. The materiality of the photo-object (much like a museum artefact) exists within an archival ecosystem or constellation of catalogues, mounts, correspondence, meeting minutes, and files, all of which I draw on for this paper—and all of which have a very real physical presence demanding some kind of attention or inattention, however unacknowledged those forms of attention, or inattention, may be. Specific archival practices may change over time; apparent revolutions, like digitization, may occur. But if the underlying structures are undisturbed, unquestioned, there is no “turn” in ways of doing, thinking, and seeing that originated in a colonial context. There is only a deep and well-worn track.

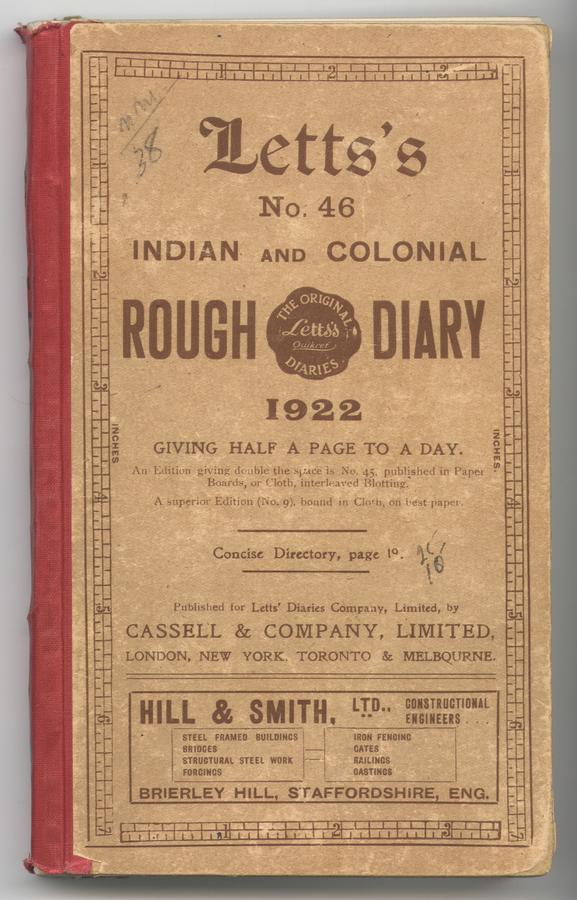

I begin not with a photo-object, but with a Letts pocket diary, the No. 46, Indian and Colonial (see Fig. 1). Letts diaries were probably the most widely used in the British empire. Both the company and the diary format had their origins in Britain’s expansionism, after all: stationer John Letts devised the diary in the early nineteenth century for his customers in London’s Royal Exchange, as a way to record movements of stock and financial transactions (McConnell 2004).

Fig. 1: Front cover of Howard Carter’s pocket diary for the year 1922 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

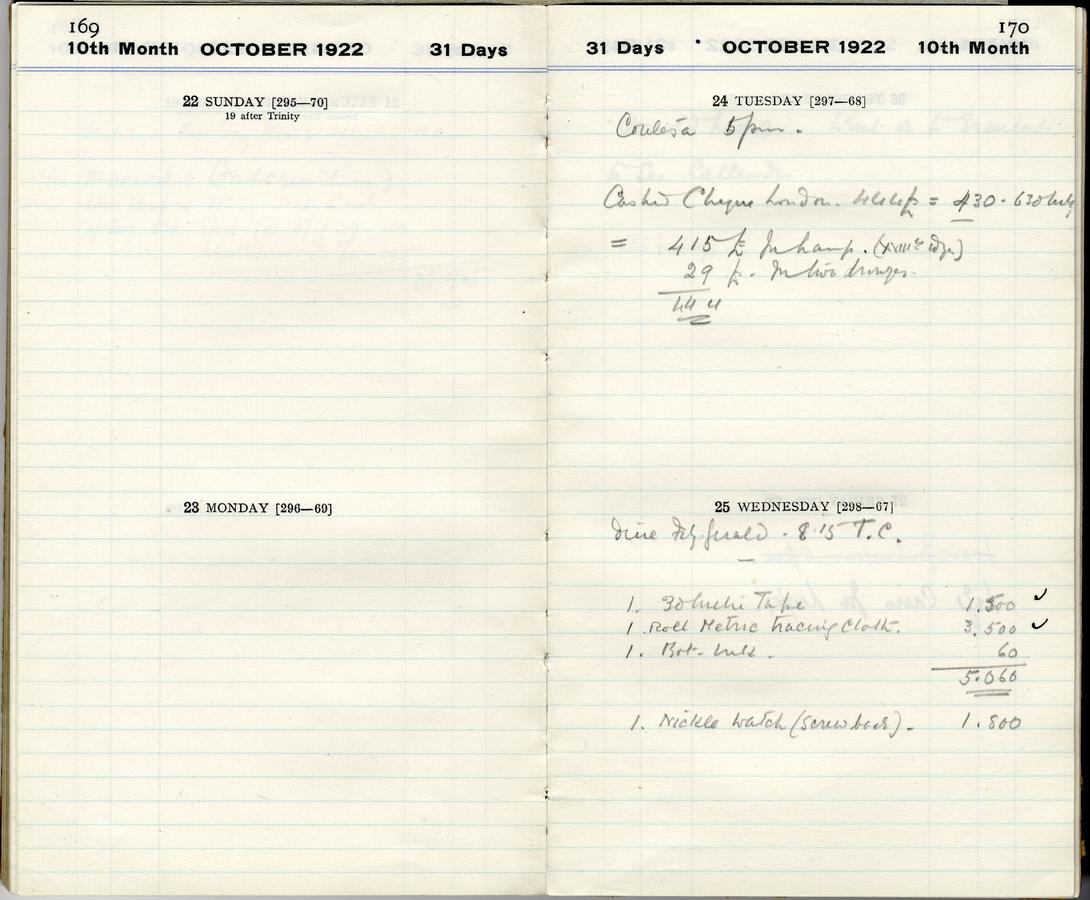

In 1922, the owner of this diary, archaeologist Howard Carter, used it for much the same purpose. In the last week of October (see Fig. 2), Carter was busy in Cairo, preparing for another winter of digging in the Valley of the Kings, 400 miles south at Luxor. His business in Cairo included a dentist’s appointment, several bank visits, and dinner at the Turf Club, favored by British civil servants (Mak 2012, 95–97). Mostly, Carter was doing his usual round of the antiquities dealers, buying and selling on his own behalf or for his employer, the Earl of Carnarvon.2 He could not know that by the end of the next week, his Egyptian excavators, led by foreman Ahmed Gerigar, would uncover the flight of steps leading to the tomb of Tutankhamun.

Fig. 2: Pages for the week of October 25, 1923 in Howard Carter’s pocket diary © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

The colonial suffuses Egyptian history in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—and suffuses the practice of Egyptian archaeology, from the name of your pocket diary, to your dentist in Cairo, to your dinners at the Turf Club, and all the transactions in between through which antiquities—and photographs—moved as both commodities and sources of scientific knowledge. (Nor was colonialism in Egypt a specifically British phenomenon: we could easily add German shipping firms, Italian grocers, and Palestinian stationers, like Edward Said’s father, to that list.) There was no archaeology without colonialism, and colonialism in an antiquities-rich country like Egypt was able to take certain forms and do certain things through archaeology. What exactly archaeologists could do in Egypt was in flux at this moment in 1922, in part because the United Kingdom had given Egypt limited independence a few months earlier, to stave off more wide-reaching demands from Egyptian nationalists. Under the UK’s unilateral terms, the British kept control of foreign affairs, the Suez Canal, and the Sudan, with a British high commissioner still in place and a British advisor in each Egyptian government ministry, including the Ministry of Public Works that oversaw the Antiquities Service—itself headed by a French Egyptologist by long-standing custom (Reid 1997).

I will return to the 1920s and Carter’s conflict with the recently empowered Egyptian authorities at the end of this paper. First, I want to look in some detail at the history of the archives and photo-objects from the Tutankhamun excavation, mindful of the question with which I began, about how archaeological archives enable the quiet perpetuation of colonial disquiet into the present day.

17.1 Making the archive: Oxford

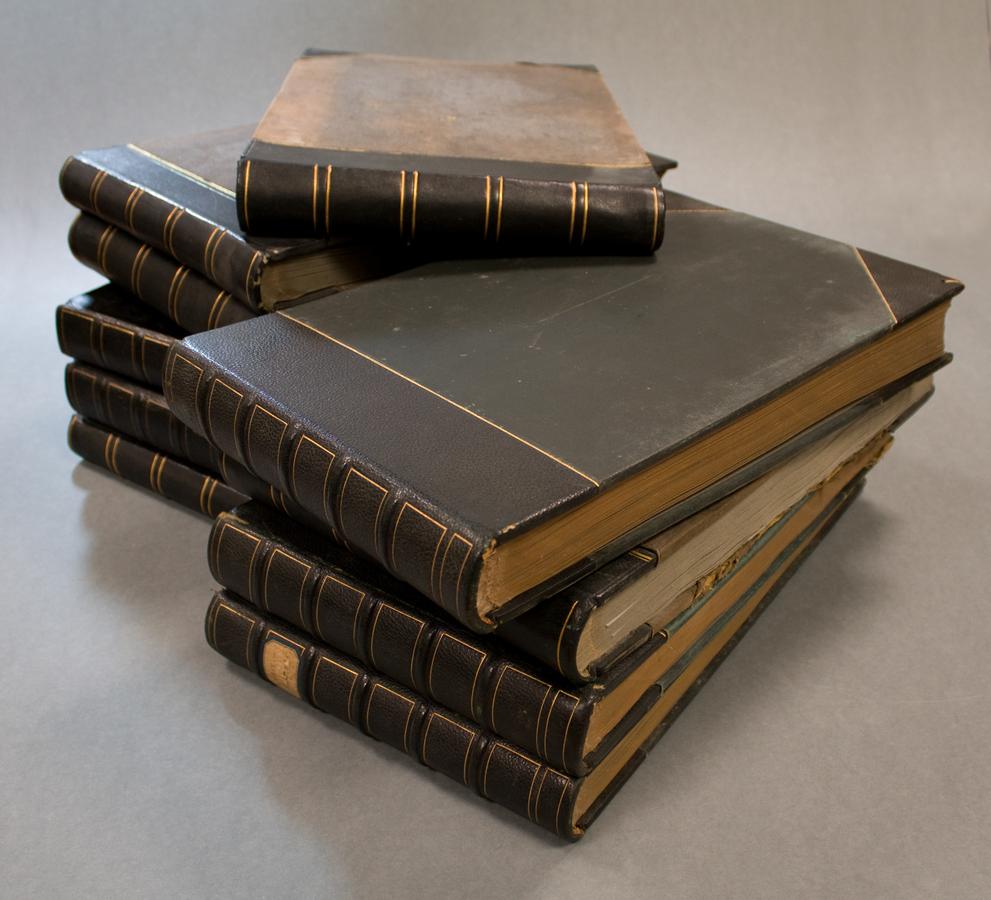

When Howard Carter died in London in 1939, his only heir, his niece Phyllis Walker, donated his excavation records to the then newly founded Griffith Institute at Oxford University, established to promote the study of Egyptology. Like most archives derived from archaeological excavations, Carter’s includes thousands of photographic objects: glass and film negatives dating from the 1910s to the 1930s, some of the metal boxes large-format negatives were shipped in, his lantern slides, and ten British-made photograph albums (see Fig. 3), which were compiled for him, probably in Egypt, by the man who did the bulk of the photography for the tomb of Tutankhamun, Englishman Harry Burton (Riggs 2016).

Fig. 3: Ten photo albums from the Howard Carter archive, compiled c. 1924–1926 by photographer Harry Burton © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

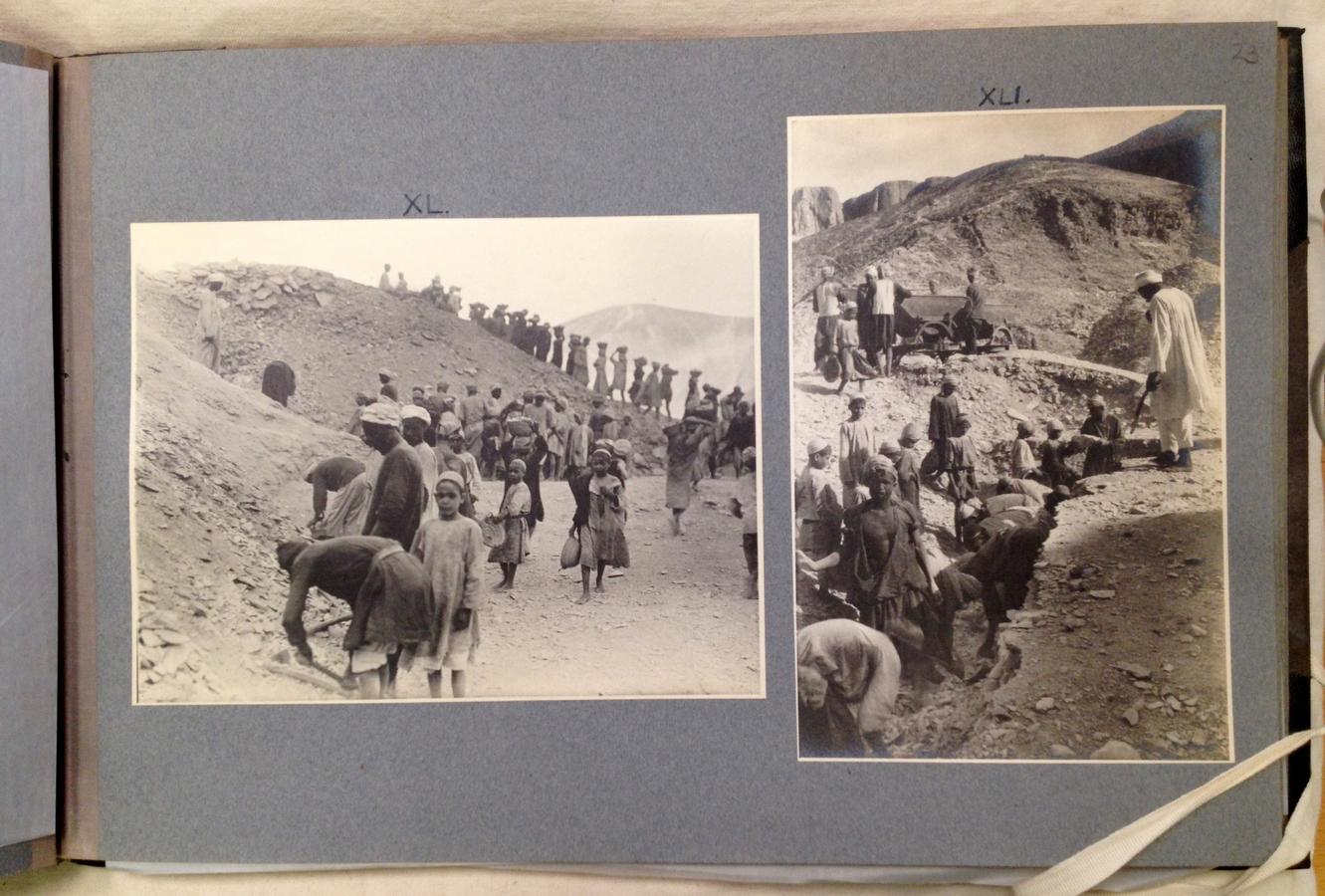

Within Egyptology, Burton’s photographs have become almost as legendary as Tutankhamun himself, to the extent that on the website of the Griffith Institute,3 all the Tutankhamun photographs in the archive are referred to collectively as “Burton photographs,” even though they include some clearly taken by other people.4 The Carter albums, for instance, contain some of his own photographs of the large-scale indigenous labor, including child labor, that went into excavation (Riggs 2016). True to the reproducibility inherent in photography, and the structuring enabled by the album format, photographs Carter had taken in January 1920 (see Fig. 4) could be printed and mounted by Burton some four or five years later, supporting Carter’s by then well-rehearsed narrative of discovering the tomb.

Fig. 4: Page from Carter album 10, with photographs printed from negatives XL and XLI; the former was taken on January 17, 1920, according to other documents in the Carter archive (see http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/cc/page/photo/335.html, accessed December 21, 2017), photo: Christina Riggs © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

Like albums, archives are formed, and re-formed, after the fact. In the 1920s, English archaeologists like Carter did not use the word “archive” to refer to what they were doing as they compiled photograph albums, excavation notebooks, and index cards. They were creating “records,” and that is how the clerical staff (always female) of the Griffith Institute would refer to this material for almost forty years. The word “archive” first appeared in the Griffith Institute’s annual reports in 1957, referring to a different group of photographs altogether (Ashmolean Museum 1957, 77). In the 1960s, the annual reports began to mention the “Egyptological archive,” until “the Archives” became a separate subheading in 1974 (Ashmolean Museum 1973–1974, 62–63). “The Carter archive” was first described as such in 1976, a full four years after “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” exhibition at the British Museum, which had been timed with the 50th anniversary of the discovery and which made use of historic photographs from the Institute’s holdings (Ashmolean Museum 1975–1976, 71; Edwards 1972). There is a tone of weary resignation in the Griffith Institute’s annual report for the year of the British Museum show, in which staff observed that Burton’s photographs had

contributed in a spectacular and admirable fashion to the exhibition in the British Museum, but could not escape notice also of the press and of innumerable publishers and broadcasting organizations in whom they inspired an insatiable desire for prints and information, stretching the capacity of the staff and photographic studio at times to their limit (Ashmolean Museum 1971–1972, 58).

In all likelihood, however, the attention the Institute received as a result of the “Treasures” exhibition was one impetus for identifying its records more explicitly as archives, and itself as (in part) an archive, in the following years.

17.2 Making the archive: New York

To see the entire photographic archive of the Tutankhamun excavation, however, we have to go from Oxford to New York, not only by way of the tomb site in Egypt—but by way of Florence. Such are the geographic bedfellows that modernity, and colonialism, helped make.

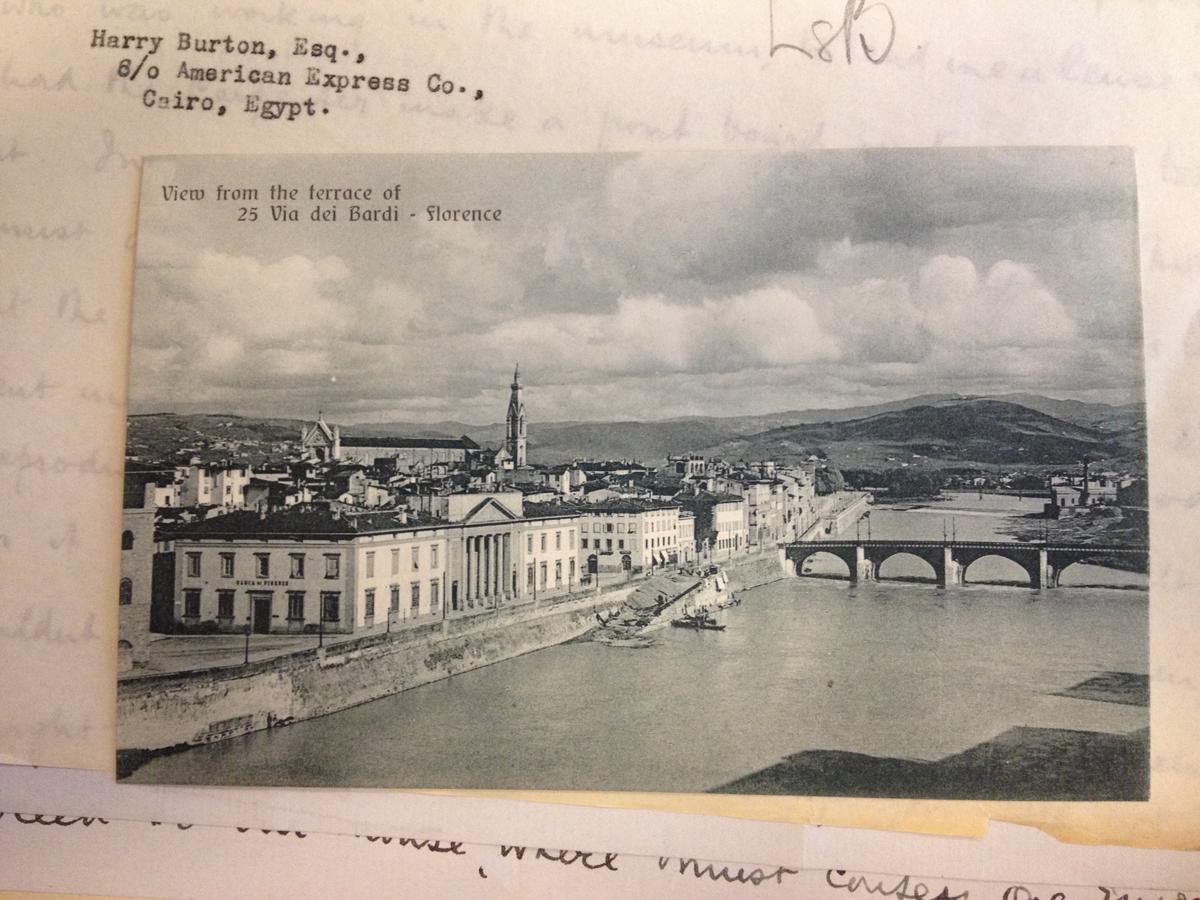

Like excavator Howard Carter (they were near contemporaries), photographer Harry Burton had left England as a teenager to make a career abroad. Carter went to Egypt in the late 1880s, Burton to Florence in the mid-1890s, as the secretary and companion of British art historian Robert Henry Hobart Cust. Burton took up photography, eventually operating a small studio on Borgo San Jacopo; through Cust, he had formed connections in the city’s Anglo-American community, earning some kind of reputation, and some independence from Cust, as a photographer of Renaissance art.5 When Cust returned to England, he ceded Burton their apartment on the Via dei Bardi (see Fig. 5). Having formed a new friendship and patronage relationship with retired American lawyer Theodore H. Davis, who wintered in Florence and Egypt and funded excavations in the Valley of the Kings, Burton entered a new phase of his life in 1910 as an archaeologist in Davis’s employ (Adams 2013, 284–87). When ill health curtailed Davis’s work in Egypt (he died in 1914), he then recommended Burton to the Egyptologists of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, to which he was an important donor.

Fig. 5: Postcard sent by Harry Burton to his employer Albert Lythgoe in New York, showing a view of Florence from the terrace of Burton’s flat, photo: Christina Riggs, used by kind permission of the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As a result, from 1914 until his death in 1940, Burton was an employee of the Museum’s Egyptian Expedition—an archaeologist, but specialized in photography. He spent every winter in Egypt, usually at Luxor, where the Museum had a luxurious dig house not far from Carter’s own home. There were long-standing personal and professional ties between the Museum and Carter (who knew its archaeologists well, and had sold it antiquities) and between Burton and Carter (who had worked closely with, and at times for, Theodore Davis, see Reeves and Taylor 1992, 71–85). Thus, when Carter announced the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922, the Metropolitan Museum was quick to offer its support, not only out of collegiality but also in hope of receiving a share of the artefacts, thanks to the generous division of finds (partage) that the Egyptian antiquities service had operated for decades, in part to encourage foreign sponsorship of excavations (Goode 2007, 71–72; Reid 2002, 93–137, 172–201).

The Museum had to settle for photographs instead because, after years of negotiations between Carter and the Egyptian government, all the tomb’s objects (officially, at least) remained in Egypt (James 2001, 447–8, 469–71). The destination of the excavation records was never up for dispute, however: they remained in Carter’s possession, with a parallel—so-called duplicate—set of negatives that he gave to the Museum, off and on, over the ten years it took to clear and record the tomb. By a gentleman’s agreement, Carter and the Metropolitan Museum’s head Egyptologist, Albert Lythgoe, planned for Burton to contribute to the photography—but without knowing how long the excavation would take (Carter at first thought two years) or how much work would be required, much less that no division of the finds would, in the end, take place. Instead, an ad hoc system emerged whereby Burton sometimes made additional negatives for the Museum, by taking two consecutive exposures, and, at other times, Carter passed on to the Museum negatives that he did not want to keep himself. Burton’s contribution was flexible, particularly in the later years of the work, when he himself did not know whether or not Carter planned to call on his services in a given season.6

Throughout the excavation, as Burton printed the negatives Carter wanted him to print, he also printed and mounted Tutankhamun photographs in the albums he kept for the Museum at its dig house, probably with the help of his wife and the dig house secretary (see Fig. 6). These albums were in the same format the Museum used for all its work in Egypt. But it was Carter who numbered the Tutankhamun negatives, and who made the final decision about which would eventually go to New York. To complicate things further, Carter used at least two sets of numbers for the photographs, and often (particularly in the first two seasons) numbered a single plate three or four times if it depicted multiple artefacts. Those were the objects that mattered, after all, not the negatives and positives we now think of as photographic objects. Although it is difficult, if not impossible, to correlate the different numbers now, Burton seems to have kept track of Carter’s system as best he could: a partial list in his hand, marked in one corner, “Keep!,” is indeed kept today with the registers that correspond to the Egyptian Expedition’s photographic archive.

Fig. 6: Page from the Tutankhamun albums compiled in the 1920s, and added to in the 1950s, for the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Christina Riggs, used by kind permission of the Museum.

That archive, though, is no longer in Egypt but in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The dig-house photograph albums were shipped “home” (as staff saw it) in 1948, when the Museum finally closed its Luxor dig house.7 At the same time, it also cleared Carter’s own nearby house, which he had left to the Museum in his will, and in doing so, sent another 500 Tutankhamun negatives to New York. These represent negatives Carter had kept in Egypt for himself, mostly from the final stages of his work at the tomb; the rest of his negatives and notes had been sent, during his lifetime, to his London address. Closing up both houses in the postwar era was no accident: it was a moment when many Western institutions sensed that change was coming and were rethinking what resources to commit to archaeology in Egypt and the Middle East (Goode 2007, 116–25; Reid 2015, 263–68).

17.3 Dividing the archive

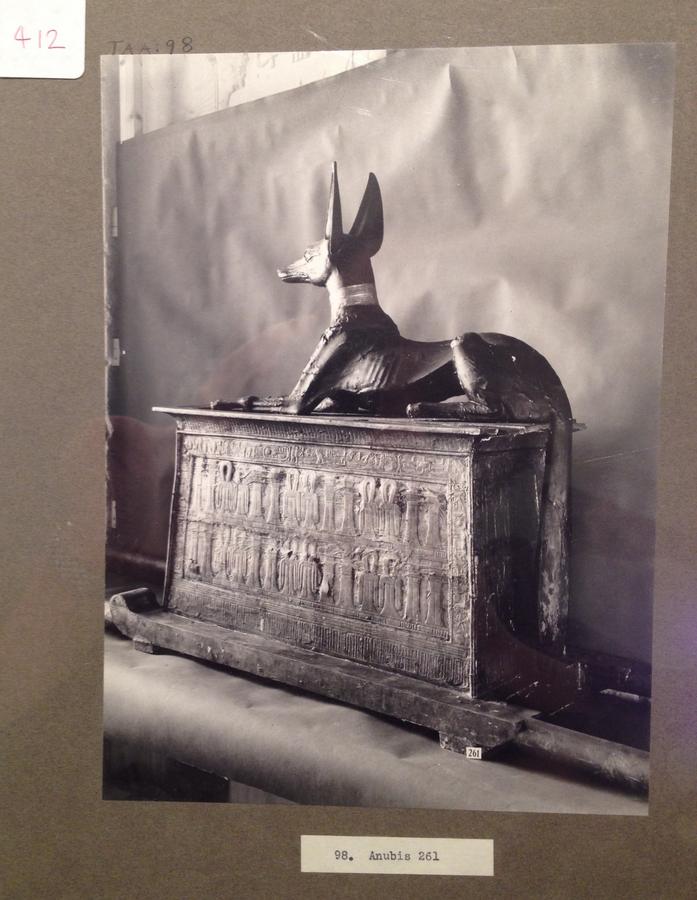

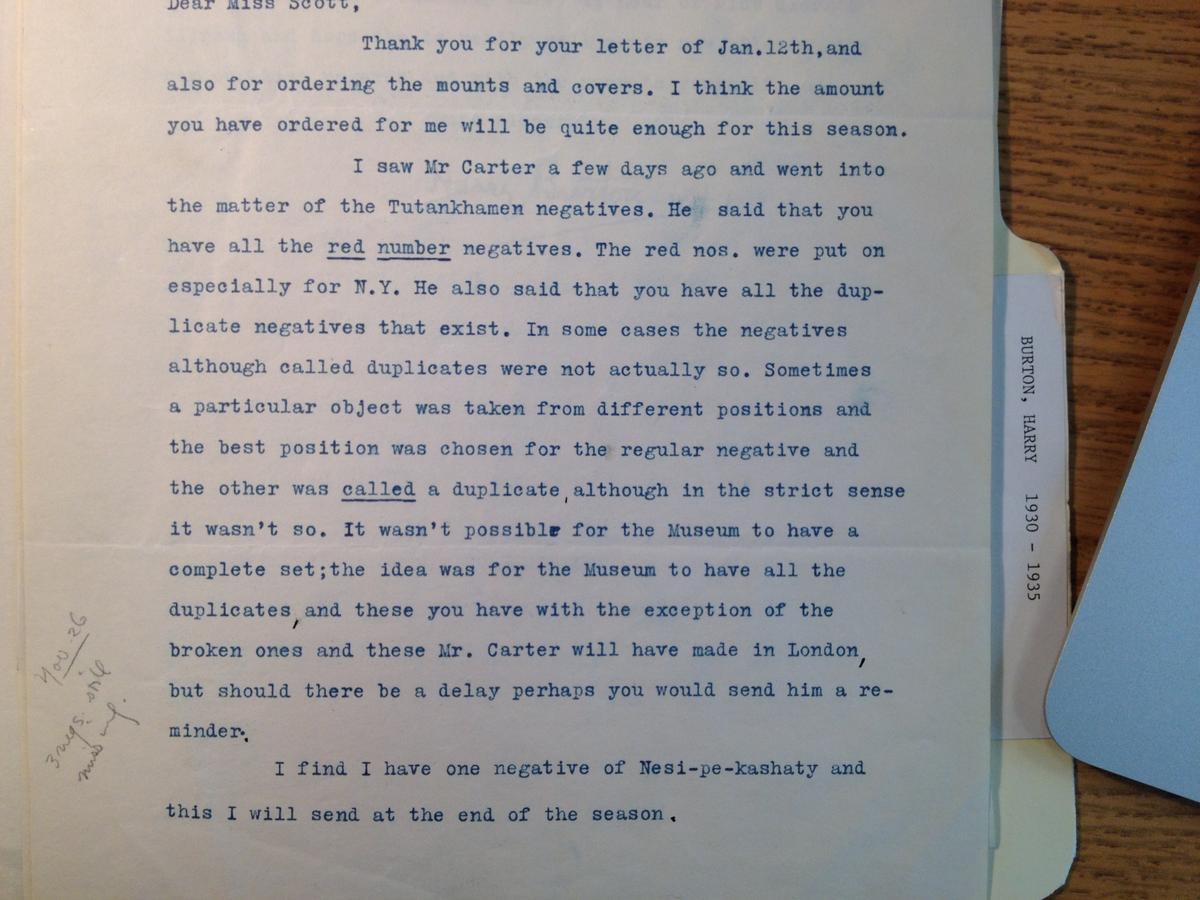

Curtailing the fieldwork of a field science like archaeology or Egyptology did not mean curtailing all the work it could do: by mid-century, institutions outside of Egypt had amassed sizeable collections not only of artefacts but also of notes, drawings, and photographs. In 1948, when the contents of its dig house and Carter’s house arrived on Fifth Avenue, the Tutankhamun material should have slotted neatly in among the negatives the Metropolitan Museum already possessed. At that time, the Museum and the Griffith Institute believed that each had essentially an identical set of photographs because of confusion over the word “duplicate.” This was a confusion Burton himself addressed in a letter to a colleague in the Museum in the 1930s (see Fig. 7), explaining that sometimes he took two negatives without changing anything, but sometimes what was called a “duplicate” was in fact a different angle or exposure of the same subject. Carter kept the best angle or exposure (the negatives now mostly in Oxford), and the Museum got the rest.

Fig. 7: Excerpt from a letter Harry Burton (Luxor, Egypt) sent to Nora Scott (New York), February 6, 1934, Burton correspondence files in the archives of the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Christina Riggs.

To this day, the Museum and the Institute to some extent persist in thinking that the photographic archive of Tutankhamun, the most famous excavation in Egyptology, is almost half the size it actually is: the Museum sometimes estimates that Burton made around 1,400 photographs (Allen 2006, 12), while the Institute suggests 1,850 (Collins and McNamara 2014, 10). The actual number is a combination of the two, or more: my own research in both archives yields a minimum estimate of 3,400 photographs surviving as negatives, positives, or both. This includes photographs by Carter, his sponsor Lord Carnarvon, or unknown photographers that have been incorporated into one or other archive, sometimes by Carter himself (as we saw with his albums above; see Fig. 4) Since neither institution has fully accounted for both negatives and positives, nor compared the original negatives in the way that scanning technology would now permit, it remains impossible to be more precise than this at present. For instance, in the current documentation of the archive, especially in Oxford, some prints identified as “new” or distinct images are cropped or rephotographed versions from a single negative, while some negatives appear never to have been printed and therefore have “disappeared,” included neither in the albums nor in the online database, as I discuss below.8

These kinds of gaps and confusions, in the best-known and most praised photographic archive in Egyptology, came as a surprise to me when I began my research with the Oxford archive in early 2015. But as Edwards and Morton (2015) have pointed out, multiplicity and reproducibility are what made photography such a useful tool, not only in the field but also in museums and archives. In addition to having staff perhaps unfamiliar with either the technical or theoretical specifics of photography, these institutions by their nature are more accustomed to dealing with singular artefacts or documents, not multiply reproducible visual material (Schwartz 1995; 2002). That the exact number, physical format, or specific date of the Tutankhamun photographs has seemed entirely untroubling to generations of Egyptologists also reflects a long-established, and difficult-to-shift, tenet of archaeology as a discipline: it does not look at the photograph but through it, as Bohrer (2011, 50) has pointed out (see also Baird 2011; Shanks 1997).

Archaeology now uses historic photographs to see site features or artefacts represented at a moment of origin that is doubly in the past—first, in antiquity and, second, at the point of discovery. Hence Egyptologists’ overriding concern with the Tutankhamun photographs has been what objects or deposition pattern they show and—especially since the British Museum “blockbuster” in 1972—the British (never Egyptian) presence in the lionized excavation. An increasing trend has also foregrounded descriptive admiration of Burton’s technical and aesthetic accomplishments (e.g. Ridley 2013). The technical aspects of his work are in some of those multiple exposures, however—as is the history of the archive, which is so crucial to any history of photography as well as the history and current practice of archaeology and Egyptology.

17.4 Reuniting the archive

An example of multiplicity in the Tutankhamun archive will serve both to exemplify one aspect of Burton’s technique, and to continue the postwar history of the archive. Burton’s correspondent back in the 1930s (see Fig. 7) was Nora Scott, who was then the most junior member of staff, eventually working her way up to become the first woman to head the Egyptian department in 1970. In the late 1940s, when the albums once kept in the dig house arrived in New York, together with the extra 500 negatives from Carter’s house, it was Scott who tried once again to make sense of the Tutankhamun photo-objects. She was put in touch with the Griffith Institute’s assistant secretary, Penelope Fox, and over almost three years, at considerable effort and expense, these two women tallied, and tried to make equivalent, the two collections.

Among many other outcomes, their work included an exchange of the large-format, 18x24cm glass negatives that Burton always worked with. A negative now in Oxford (see Fig. 8) bears the number “137,” followed by “dup” for duplicate. But at the edge of the emulsion, the lettering “TAA 964” is the number the Metropolitan Museum had used to label its own share of the negatives. When Scott saw that the Museum already had a negative showing the subject of this image, Box 101 from the tomb’s antechamber, she dispatched this glass negative, with several others, to Oxford.

Fig. 8: A Burton negative depicting object 101 from the tomb, given first to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where it was number TAA 964), then sent to the Griffith Institute in Oxford, reversed digital scan from the 18x24 cm glass plate © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

There, Fox discovered that the Griffith Institute also already had a negative showing Box 101, the negative Carter had preferred, with his number “137” written on it (see Fig. 9). In this negative, compared to the others, Burton adjusted the swing and tilt mechanisms of his view camera to help square the box on the plate, presumably so that the hieroglyphic inscription at its near end would be at a more legible angle to the viewer while still preserving the sense of depth created by the box’s slanted position in relation to the camera lens.

Fig. 9: Carter’s negative of object 101, now negative P0137 in the Griffith Institute, reversed digital scan from the 18x24 cm glass plate © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

Of the three photographs (that is, the three exposed negatives) that Burton had thus taken of this box, from this angle, he printed only one—the one Carter preferred and that Oxford already owned via the bequests from his niece in 1939 and 1946.9 Because of difficulties both Scott and Fox faced when comparing negatives and prints in their own and each other’s collections, such confusions easily arose. Fox in particular faced the challenge of working largely from negatives, attempting to identify what were sometimes minute differences.10 It was easier to go by subject matter—Box 101—and so all three of the separate negatives became conceived as one, and only the negative Burton printed appears on the relevant database entry for Box 101.11

In the correspondence files of the Griffith Institute, there are hints of unease about what else the photographs might have represented in the immediate postwar era. Its then director Edward Thurlow Leeds (the role was ex officio for the Ashmolean Museum’s Keeper of Antiquities) sought advice from colleagues in the university, at the British Museum, and, on the grapevine, from Cairo about whether the Egyptian government might have a claim on the Tutankhamun records, in particular the photographs: would it be a problem, for instance, if Oxford licensed them for printing? Learning that the Museum in Cairo had begun to take its own photographs of the objects seems to have assuaged these concerns, one photograph being as good as another.12 To be on the safe side, however, the next director of the Griffith Institute, Donald B. Harden, and the head of the Egyptian department at the Metropolitan Museum, Ambrose Lansing, agreed only to charge for commercial use of the photographs, anxious not to be seen making a profit from the tomb’s legacy.13

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Nora Scott and Penelope Fox undertook their collation and exchange of Tutankhamun photographs, any concerns about the Egyptian government’s potential interest in the tomb records had been put to rest—but in the background will have remained other concerns about the future of Egyptology in Egypt. Fox presented her final report of the successful collation exercise to the Griffith Institute’s management committee on January 24, 1952—two days before “Black Saturday,” when Cairo erupted in anti-British riots (Kerbouef 2005).14

When Fox married and left her post that spring, she must have thought that the Tutankhamun archive was now complete. Her laboriously typed, 65-page guide to the New York and Oxford collections remained a consultation document until the creation of a computerized database in the 1990s, but an archive, by its nature, is never fixed and never complete. Within months of Fox’s departure, her successor Barbara Sewell was writing to Nora Scott in New York again, acknowledging receipt of further Tutankhamun prints and listing corrections both women should make to their respective copies of the guide:

Thank you for setting out so clearly the latest (perhaps it is wiser not to say ‘final’!) developments of the Tutankhamun exchange. I must say, I am not sorry to have come in at the end of this stupendous task […] - it must have been a real headache at times.15

Collations, renumberings, and reorderings of the Tutankhamun prints and negatives in the Griffith Institute would continue at intervals for decades, and are ongoing as I write.

In 1980, the Griffith Institute, by then conscious of itself as an archive, commissioned a conservator to evaluate its photographic holdings.16 Acting on this advice, the Ashmolean Museum’s photographic studio “cleaned,” that is, refixed, many of Burton’s glass plates and made a fresh set of prints from most of them. During this time, they also made hundreds of copy negatives from prints that had no original negatives in Oxford; these copies, made on Kodak SO-015 film sheets, were also printed to “complete,” once again, the archive. Prints of a mixed quality and from mixed sources were then scanned in the late 1990s by a commercial firm and put online in one of the earliest digitization projects in Egyptology.17 Low image resolution further reduced the quality of the images, due to the limitations websites then faced in terms of file sizes and storage capacity. However, it remains the presentation—the “Anatomy,” as it is called—of the Tutankhamun excavation online. It presents itself as the “definitive archaeological record,” as if it has perfected what Scott and Fox began a generation earlier, and Howard Carter and Harry Burton before that.

17.5 Repeating the archive

For all its materiality, its physical presence, its unwieldy heft, it is the archive itself that keeps insisting on the priority of the photographic image rather than the photographic object. However many changes in values, use, or format may occur, it is as if there is a quality of stasis or suspension in the archival project from its beginnings, where something—a way of seeing, filing, thinking—is set down with such weight that further movements serve to make a groove and dig that well-worn track. Practices that have their own rationale at one moment in time, in part to deal with the physicality of the archive, inevitably look back on previous practices—and we are meant to look back, directly, at the heroic archaeology of the 1920s and the golden boy king.

The producers of a 2016 British miniseries dramatizing the tomb’s discovery had clearly studied photographs of the excavation closely not only for set designs, but also for publicity stills, such as one that showed actor Max Irons in the role of Carter, working in solitude on Tutankhamun’s innermost gold coffin.18 The publicity shot, however, excluded the Egyptian ra’is working at Carter’s side, one of three or four experienced Egyptian excavators who, like Burton, worked on the Tutankhamun excavation throughout. In the source photograph (see Fig. 10), the two men work side by side, both holding still while Burton took the shot; the ra’is is meant to be brushing away the resin coating Carter is hammering off the coffin. It was one of the last of such staged “work-in-progress” photographs Burton would take, although he continued to photograph the tomb and its artefacts until January 1933. Intended for Carter’s own publicity purposes in the lead-up to the unwrapping of the royal mummy (still safely inside the coffin), the photograph appeared in The Illustrated London News on February 6, 1926, was reproduced as a cigarette card in the 1930s (Collins and McNamara 2014, 101), and was reactivated in the American tour of the Tutankhamun “treasures” (Cone 1976, 2). It has not been out of circulation since: it has a busy existence on the internet and in commercial photo libraries,19 and I have often seen it—in the offices of museums and archives, for instance—turned into a “spoof” image by pasting someone else’s face over the head of the Egyptian man, never of Carter.20

Fig. 10: A copy negative dating c. 1930–1960, reversed digital scan from the 12x16 cm glass plate, now negative P0770 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

There was always an outward face to the Tutankhamun archive: in the 1920s, Carter and Lord Carnarvon licensed Burton’s photographs to The London Times and The Illustrated London News to help finance the work—a move that thoroughly angered the Egyptian press and rival British and American papers (Colla 2007, 172–226; Reid 2015, 51–79). Conflict over who controlled the tomb, and who would present it to the public, led to a falling-out between Carter and Egyptian officials, including the French head of the antiquities service. At the time this photo was taken, he had only just returned to work, after the downfall of the nationalist Egyptian government and the installation of a more pro-British caretaker government.

In archaeology, the photographic image remains stubbornly fixed as an “objective” record of a site or an artefact, or as a self-regarding snapshot of Egyptologists in action. Such photographs easily lend themselves to the colonial or imperial nostalgia that plays all too well in mainstream culture, as well as in the discipline’s performance of itself. The history of the Tutankhamun archive demonstrates that disciplinary replication is bottom-up as much as top-down, that is, it takes place in the work of “invisible technicians” like Penelope Fox and the photographic studio as much, sometimes more than, in the work of professors or editorial board meetings (Shapin 1989). For the almost thirty-year period between Carter’s last—and popular—book on the tomb (Carter 1933) and the 1960s launch of an academic series publishing tomb objects in more detail,21 the work that Nora Scott, Penelope Fox, and other essentially clerical-level (and largely female) staff did with the archive was the most sustained and substantial attention the tomb of Tutankhamun received.22 Fox in fact published her own book on the tomb, reproducing a number of the Burton photographs from the Griffith Institute holdings for the first time (Fox 1951). The Griffith Institute described it as a “picture-book” and hoped it would generate income (Ashmolean Museum 1951, 71). It has largely been forgotten.

There are both disciplinary and institutional factors that contribute to examples like the one with which I opened this paper, whereby a colonial establishment still operating in Egypt unquestioningly, no doubt unwittingly, has adopted an Orientalist “Other-ing” to present its photographic archive, juxtaposing humans and objects as if they were ethnographic types and publicizing the results with suitably “exotic” musical accompaniment. One factor is that most excavation archives are cared for within archaeological institutions of some kind, often those that first sponsored the work. The archive is thus at the heart of disciplinary history and identity; it is the foundation myth and mirror of an entire field of study. Another factor, already touched on, is the methodological focus of archaeology and Egyptology on image content, which takes photography as a means of direct access to the object “in” the photograph, en route to accessing antiquity itself. Moreover, the distinctive features or technical issues that a photographic archive presents (such as copy negatives) are outside the expertise or interest of most archaeologists, and for that matter, many archivists as well. The result is that institutions holding excavation archives may lack technical and theoretical awareness as well as a capacity or inclination for critique; each of these factors in turn may amplify the others.

In this paper, the history of the Tutankhamun archive shows that it is not the photographic image alone that has made the well-worn track between Egyptology’s colonial past and its present day. Rather, it is the photo-object, its archival lives, and the information and ideas with which they file, label, stick, and stamp it. Archival practices carry traces of the knowledge communities, power structures, and value systems in which photographs were created and used, as surely as the photographic image carries traces of what was in front of the camera at a given moment in time. New cataloging, rephotography, scanning, conservation interventions: all such practices serve only to compound or mask the issues at stake if they are used without critical and historical awareness. Throughout its almost one hundred years of existence, the photographic archive of the Tutankhamun excavation has been “brought up to date” or “made complete” several times, and each instance has contributed to, even impelled, the normalization and sublimation of colonial knowledge formations and visualities. No matter how iconic an image may be, and many of the Tutankhamun photographs certainly are, we must look beyond the image and into the archive in order to understand—and confront—the fact that photo-objects, like Egyptian pharaohs, have long and powerful afterlives.

17.6 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Front cover of Howard Carter’s pocket diary for the year 1922 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 2: Pages for the week of October 25, 1923 in Howard Carter’s pocket diary © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 3: Ten photo albums from the Howard Carter archive, compiled c. 1924–1926 by photographer Harry Burton © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 4: Page from Carter album 10, with photographs printed from negatives XL and XLI; the former was taken on January 17, 1920, according to other documents in the Carter archive (see http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/cc/page/photo/335.html, accessed December 21, 2017), photo: Christina Riggs © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 5: Postcard sent by Harry Burton to his employer Albert Lythgoe in New York, showing a view of Florence from the terrace of Burton’s flat, photo: Christina Riggs, used by kind permission of the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

• Fig. 6: Page from the Tutankhamun albums compiled in the 1920s, and added to in the 1950s, for the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Christina Riggs, used by kind permission of the Museum.

• Fig. 7: Excerpt from a letter Harry Burton (Luxor, Egypt) sent to Nora Scott (New York), February 6, 1934, Burton correspondence files in the archives of the Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Christina Riggs.

• Fig. 8: A Burton negative depicting object 101 from the tomb, given first to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (where it was number TAA 964), then sent to the Griffith Institute in Oxford, reversed digital scan from the 18x24 cm glass plate © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 9: Carter’s negative of object 101, now negative P0137 in the Griffith Institute, reversed digital scan from the 18x24 cm glass plate © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

• Fig. 10: A copy negative dating c. 1930–1960, reversed digital scan from the 12x16 cm glass plate, now negative P0770 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

17.7 References

Adams, John M. (2013). The Millionaire and the Mummies: Theodore Davis’s Gilded Age in the Valley of the Kings. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Allen, Susan J. (2006). Tutankhamun’s Tomb: The Thrill of Discovery. New York, New Haven, and London: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press.

Ashmolean Museum (1951). Report of the Visitors, 1951. Charles Batey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– (1957). Report of the Visitors, 1957. Charles Batey. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– (1971–1972). Report of the Visitors, 1971–2. Vivian Ridler. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– (1973–1974). Report of the Visitors, 1973–4. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

– (1975–1976). Report of the Visitors, 1975–6. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baird, J. A. (2011). Photographing Dura-Europos, 1928–1937: An Archaeology of the Archive. American Journal of Archaeology 115(3):427–446.

Bohrer, Frederick N. (2011). Photography and Archaeology. Exposures Series. London: Reaktion Books.

Capart, Jean (1943). Tout-Ankh-Amon. Brussels: Vromant.

Carter, Howard (1933). The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, Volume III. London: Cassell.

Colla, Elliot (2007). Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Collins, Paul and Liam McNamara (2014). Discovering Tutankhamun. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

Cone, Polly, ed. (1976). Wonderful Things: The Discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Driaux, Delphine and Marie-Lys Arnette (2016). Instantan és d’É gypte: Trésors photographiques de l’Institut Fran çais d’Arch éologie Orietnale. Cairo: l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orietnale.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Christopher Morton (2015). Between Art and Information: Towards a Collecting History of Photographs. In: Photographs, Museums, Collections: Between Art and Information. Ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton. London: Bloomsbury, 3–23.

Edwards, IIorwerth E. S. (1972). Treasures of Tutankhamun. London: Thames and Hudson.

Fox, Penelope (1951). Tutankhamun’s Treasure. London, New York, and Toronto: Oxford University Press and Geoffrey Cumberlege.

Goode, James F. (2007). Negotiating for the Past: Archaeology, Nationalism, and Diplomacy in the Middle East, 1919–1941. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hagen, Fredrik and Kim Ryholt (2016). The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880–1930: The H.O. Lange Papers. Copenhagen: Royal Danish Academy of Science and Letters.

Hornung, Erik and Marsha Hill (1991). The Tomb of Pharaoh Seti I. Zürich and Munich: Artemis.

James, T. G. H. (2001). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun. London and New York: Tauris Parke. First edition 1992.

Johnson, George B. (1997). Painting with Light: The Work of Archaeology Photographer Harry Burton. KMT 8 (2):58–77.

Kerbouef, Anne-Claire (2005). The Cairo Fire of 26 January 1952 and the Interpretations of History. In: Re-Envisioning Egypt 1919–1952. Ed. by Arthur Goldschmidt, Amy J. Johnson, and Barak A. Salmoni. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press, 194–216.

Mak, Lanver (2012). The British in Egypt: Community, Crime and Crises 1822–1922. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

McConnell, Anita (2004). Letts, Thomas (1803–1873). In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. (Visited on May 26, 2017).

Reeves, C. N. and John H. Taylor (1992). Howard Carter before Tutankhamun. London: British Museum Press.

Reid, Donald Malcolm (1997). Nationalizing the Pharaonic Past: Egyptology, Imperialism, and Egyptian Nationalism, 1922–1952. In: Rethinking Nationalism in the Arab Middle East. Ed. by James P. Jankowski and Israel Gershoni. New York: Columbia University Press, 127–149.

– (2002). Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. Berkeley: University of California Press.

– (2015). Contesting Antiquity in Egypt: Archaeologies, Museums and the Struggle for Identities from World War 1 to Nasser. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press.

Ridley, Ronald T. (2013). The Dean of Archaeological Photographers: Harry Burton. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 99(1):117–130.

Riggs, Christina (2014). Unwrapping Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury.

– (2016). Shouldering the Past: Photography, Archaeology, and Collective Effort at the Tomb of Tutankhamun. History of Science 55(3):336–363.

– (2017). The Body in the Box: Archiving the Egyptian Mummy. Archival Science 17(2):125–150.

Schwartz, Joan M. (1995). ‘We make our tools and our tools make us’: Lessons from Photographs for the Practice, Politics, and Poetics of Diplomatics. Archivaria 40:40–74.

– (2002). Coming to Terms with Photographs: Descriptive Standards, Linguistic ‘Othering,’ and the Margins of Archivy. Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists 54:142–171.

Shanks, Michael (1997). Photography and Archaeology. In: The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representation in Archaeology. Ed. by Brian Leigh Molyneux. London / New York: Routledge, 73–107.

Shapin, Steven (1989). The Invisible Technician. American Scientist 77(6):554–563.

Footnotes

See https://youtu.be/r5ZpjQ-UzTc, accessed December 21, 2017.

For the antiquities trade in Egypt, see Hagen and Ryholt 2016.

See http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/discoveringtut/, accessed December 21, 2017.

For Burton’s work in Egypt, from the perspective of Egyptology, see Hornung and Hill 1991, 27–30; Johnson 1997; Ridley 2013; Collins and McNamara 2014, 34–43, as well as https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/harr/hd_harr.htm, accessed December 21, 2017.

Some of Burton’s photographs can be viewed online in the catalog of the Kunsthistorisches Institut, Florence. See http://photothek.khi.fi.it/gallery/pic-gesamt/burton, accessed December 21, 2017.

The contingent nature of his work for Carter crops up regularly in Burton’s correspondence with Museum colleagues, particularly after the Antiquities Service let Carter resume work at the tomb in 1925: letters from Burton to Alfred Lythgoe, March 17, July 7, and September 13, 1925 and July 3, 1928; to Herbert Winlock, March 9, 1926; and from Winlock, July 3, 1928 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art, Burton correspondence files).

Nora Scott (New York) to Donald B. Harden (Oxford), June 8, 1949 (Griffith Institute, NYMMA Photos file, Acquisitions—Gifts Accepted. MMA—Tutankhamun material 1949–50).

Two of several examples of “new” or distinct photographs from the Griffith Institute’s online database: negative P1710 is a copy negative, c. 1980s, replicating a print from negative TAA1096 (New York), and P0598A is not a separate negative but a print probably from P0598 (Oxford) or TAA45 (New York). One of several examples of “disappeared” negatives: P1298 (Oxford) appears only once in the online database, but there are three large-format glass negatives with this number in the Griffith collection, each taken with different adjustments to the camera. In addition, several dozen prints of the burial shrines, for which no negatives exist, are excluded from the Oxford database.

Carter’s notes on the tomb were first offered in 1939 as a loan, then in 1946 as a gift, at which point his niece added the glass negatives and his lantern slide collection (Griffith Institute, correspondence for the Carter Deposit, file Carter 194546).

Fox complained about working from negatives in a letter to Nora Scott, March 15, 1952 (Griffith Institute, NYMMA Photos file, Acquisitions MMA photogr. Tut Corres. 1952–). Carter’s set of photograph albums was only donated in 1959, after the Fox and Scott collation took place.

See http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/carter/101.html, accessed December 17, 2017.

Relevant letters in Griffith Institute, correspondence for the Carter Deposit, file Carter 194546.

For example, letters from Lansing to Harden, July 7, 1946, and from Harden to Egyptologist Jean Capart, December 14, 1945 (in same file as preceding note).

Griffith Institute, NYMMA Photos file, under Acquisitions MMA photogr. Tut Corres 1951.

Barbara Sewell to Nora Scott, October 9, 1952 (Griffith Institute, NYMMA Photos file, Acquisitions MMA photogr. Tut Corres. 1952 –).

Report by Anna Western, January 23, 1980 (Griffith Institute, correspondence for the Carter Deposit, file Carter 1978–80).

See http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/discoveringtut/, accessed December 21, 2017.

It is available on the last page of the press pack and appeared in a range of print and online media: https://web.archive.org/web/20161019190956/http://presscentre.itvstatic.com/presscentre/sites/presscentre/files/tutankhamun_itv.pdf, accessed December 21, 2017.

See https://www.alamy.com/BTKGC8, accessed December 21, 2017.

Staff at the Griffith Institute advised me that they had been unaware their negative was not an original until they came to scan it for an Ashmolean Museum exhibition (“Discovering Tutankhamun”: Collins and McNamara 2014).

See list at http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/5publ.html, accessed December 21, 2017.