By examining the case of the Photothèque of the Musée de l’Homme, created in 1938,1 and its original material conception, this paper intends to question the values attached to photographs and the means by which the photographs acquire these values. The study of the materiality of photographic objects, which has been promoted by the works of Elizabeth Edwards in particular, undoubtedly provides a good entry point into these issues.2 Studies conducted along this line have highlighted a number of mechanisms that bring scientific and historical values to images. However, they have too often overlooked another aspect: the commercial value of images. Only the analyses focusing on structures with an explicit commercial orientation (photo agencies, image banks, etc.) have directly addressed this question.3 These organizations, mainly emerging after the 1920s, deserve specific attention. But does this mean that they led to a division of labor and prerogatives between those in charge of selling and distributing images on the one hand and, on the other, institutions such as scientific museums that were more concerned with accumulating documentary photographs and constituting scientific collections?4 Although there was an indisputable specialization process affecting photographic institutions at the time, the case of the Photothèque of the Musée de l’Homme suggests that such a dichotomy should be put into perspective.

The museum’s photographs, which had the quality of documentary and scientific objects in line with the status assigned to them since the end of the nineteenth century by anthropology (Edwards 1992) and the sciences in general (Daston and Galison 2007; Mitman and Wilder 2016), took on an added commercial value promoted by the museum. Under the initiative of the museum’s director, Paul Rivet, the various actors involved in the Photothèque created a “commercial department” (service commercial) with the aim to make photographs available to clients and to reproduce and sell them to illustrated journals, publishers, or private individuals. It was also designed to expand by storing all the collections of prints provided to the museums by its collaborators.5 The creation of this department involved a specific reorganization of all images and the individual treatment of photographs, which were arranged in a completely new fashion. Therefore, economic aspects had an impact on the materiality of the museum’s vast photographic collections, as much as on their scientific uses, as mentioned above (Barthe 2000). The accumulation and creation of documentary collections on the one hand and the commercial distribution of images on the other hand were considered to be two sides of the same coin: the Photothèque was designed as a tool to promote the numerous photographs collected and preserved by the museum.

One of these promotional means was the presentational form of images, which were individually pasted onto standardized color-coded card mounts. This system was the result of numerous experiments and innovations which took place at the museum during a relatively short time frame around 1938. As suggested by Elizabeth Edwards, building on the works of Christine Barthe, such a “regularity of the physical arrangement” of images created “an equivalence between them” (Edwards 2002, 71). According to these two authors, who have borrowed Johannes Fabian’s critical approach (Fabian 1983), these material aspects, along with other organizational elements such as division into geographical areas and ethnic groups, helped to construct and develop anthropological narratives behind which the discipline concealed the historicity of its objects of study. Thanks to the recent rediscovery of the Photothèque’s archives at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac,6 these narratives, which have stressed the epistemological effects resulting from how the photographs were classified, deserve further investigation: one must take into account the underlying economic objectives behind the arrangement of these collections, so as to have a finer and more comprehensive understanding of what was at stake in the constitution of these photographic collections. We need to develop a more precise vision of these processes of accumulation and arrangement of images, which are not systematically deprived of any commercial motives.

The organizational plans of the Photothèque, resulting from the efforts of a man named Odet de Montault,7 reveal shifting ideas on the manufacturing and format of the cards holding the photographs. The solution chosen at the time was used until the 2000s when the Photothèque was closed down and the photographs transferred to the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac.8 After reviewing the hesitations and the different options considered for the cards—those that were abandoned as much as those that were finally adopted—, I will examine what these choices materialize. They reflect a pioneering attention on the part of the Photothèque, which was then embracing the model of a modern photo agency, to photographers who were given a legal status based on the recognition of their right to their own images. On the other hand, the materiality at work also contributed to making these images available for sale and distribution by explicitly insisting on their status as commodities.

12.1 Materialized values: the origin of a codification

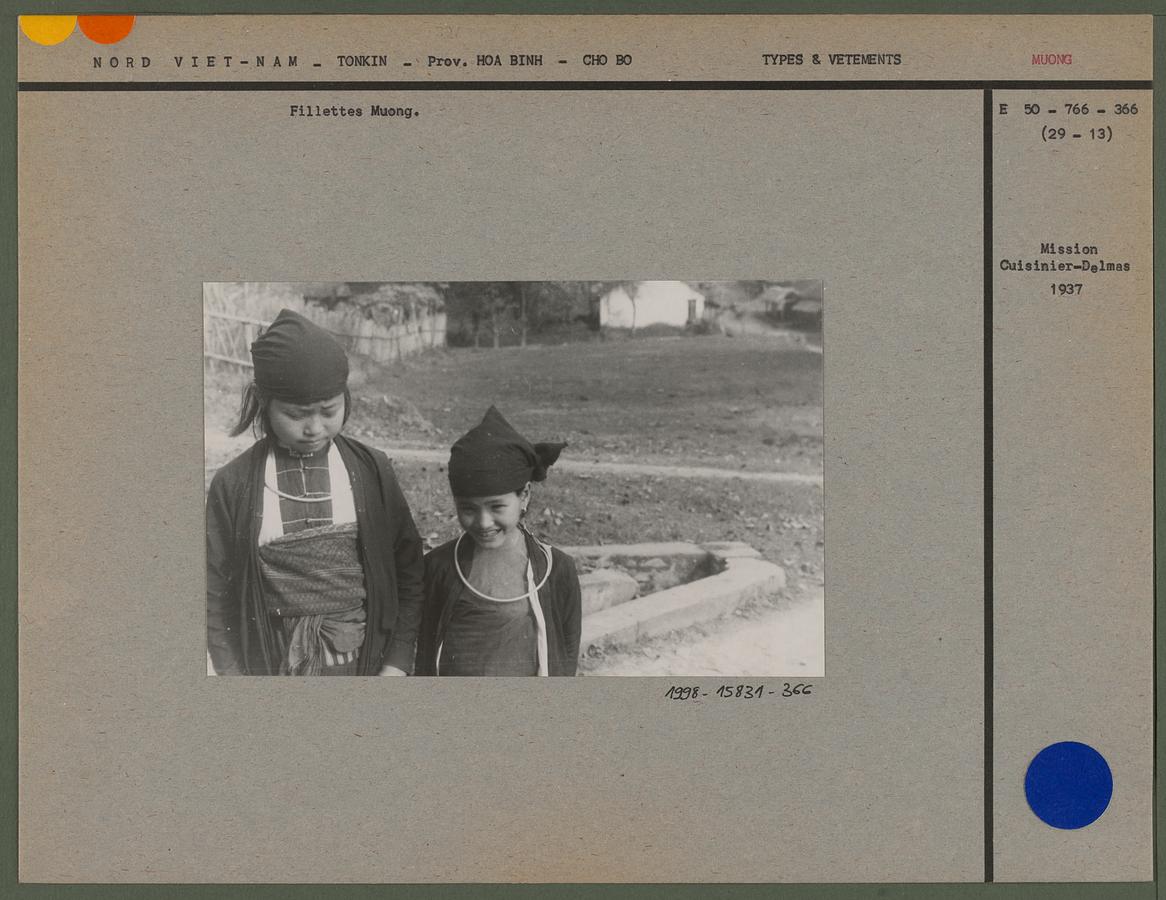

Fig. 1: Fillette Muong (Young Muong girls), Vietnam, mission Cuisinier-Delmas, Lucienne Delmas or Jeanne Cuisinier, 1937, baryte print, 10.3 x 16 cm (photo), 22.5 x 29.3 cm (cardboard), Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, inv. no. PP0005858.

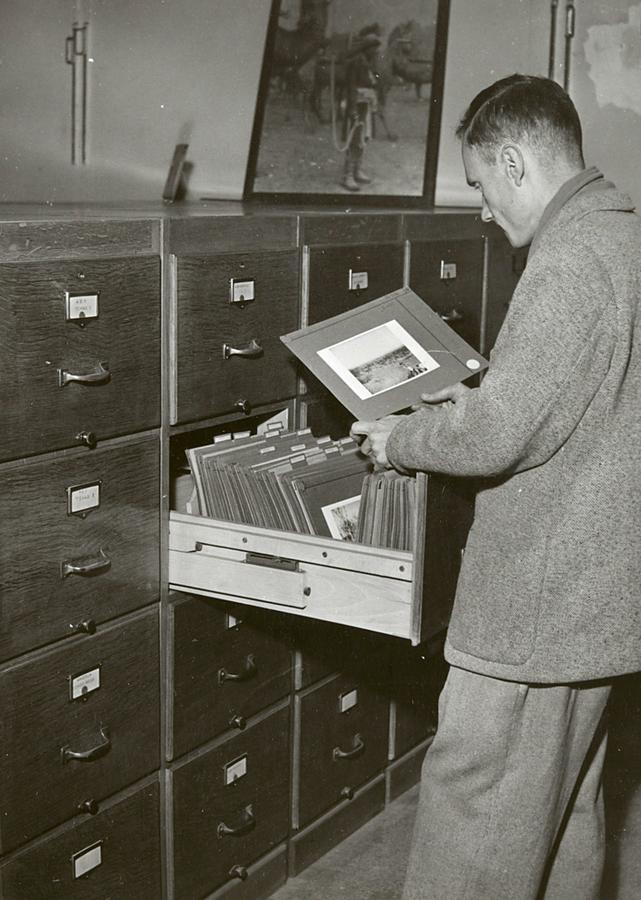

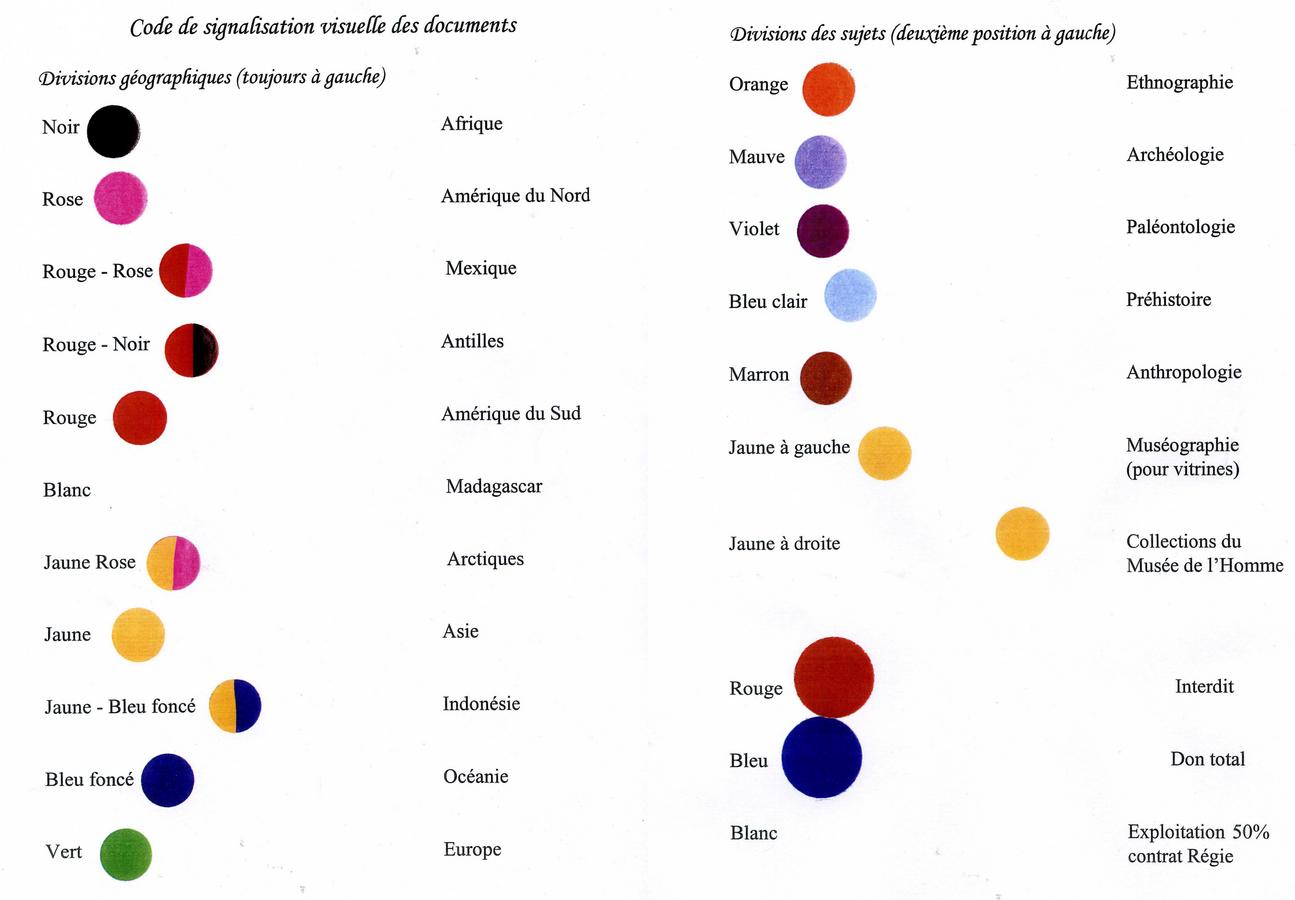

On the card mounts that composed the photo library until it closed, the image is placed at the center and surrounded by various colored labels (see Fig. 1). In the top left-hand corner of the photograph entitled “Young Muong girls” (Fillettes Muong), for instance, which was taken during a field trip to Indochina that Lucienne Delmas participated in before she became responsible for the museum’s photographic fund,9 the yellow geographic label denoting Asia is juxtaposed with the label indicating the disciplinary field to which the image belongs,10 that is, in this case, ethnology. Both stickers overlap the edge of the cardboard, meaning the colors are visible—and thus the information they refer to—without having to pull the card out from the filing cabinet (see Fig. 2). Christine Barthe has already studied these labels and has underlined in particular the fact that the importance attached to geography in the general arrangement of photographs, as represented by the first sticker, reinforced the division of ethnology into various areas at the expense of a historicized approach to its objects of study (Barthe 2000). The colors chosen reflected a caricatured and racial vision (see Fig. 3) inherited from Linnaeus.11

Fig. 2: Salle de travail de la Photothèque (Working room in photo library), Musée de l’Homme, Diloutremer, c.1950, baryte print, 22.5 x 29.5 cm (cardboard), Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, inv. no. PP0090871.

Fig. 3: Code de signalisation visuelle des documents (Color code for documents), Lucienne Delmas, c. 1950, 2 pages, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

A third label was added to the two mentioned above. Located in the bottom right-hand corner, it has been paid little attention although it is even bigger than the other two.12 Its presence there and its color answer another question, one which is quite unusual in the context of a scientific museum: terms and conditions for the commercial use of photographs. The color blue meant that the image was owned by the museum. As its owner—whether the author was the museum’s photographic department or a private individual who had surrendered his or her rights—the museum could have disposed of the image, sold reproductions, and reaped all the benefits. The other possible colors were white or red, according to legal terms of use. These colors represent the three different legal or commercial statutes of images in the Photothèque, with no relation to any geographic or disciplinary category. This classification was implemented by Odet de Montault around 1939, and yet it was quite vague: neither the code nor the meaning that the code finally came to refer to had been originally fixed.

In one of his first drafts, Montault had only planned to distinguish between two kinds of images: photographs “of objects belonging to the museum taken outside their original environment [and those] of the museum display” on one hand and, on the other, “photographs taken outside the museum.”13 Such a distinction was based on the observation that different uses corresponded to different images, some being much more important visual tools than others and playing a decisive role in the internal organization of the museum14 and in the promotion of its activities, particularly through the printed media. This fundamental difference, which was at the essence of the photographs, had to be visible in the material itself, that is, the color of the cards holding the photographs. Even though Montault did not challenge the use of cards measuring 22.5 by 29.5 centimeters already used at the museum,15 he suggested that images related to the museum’s life should be “pasted on a brown card,” while those coming from outside should be “pasted on a grey card.”

This distinction, which was based on the content and origin of images, was soon to be replaced by another, as evidenced by Montault’s more detailed plans of October 1938. It was driven by the commercial goals of the Photothèque. According to Montault, “the commercial use of the new photo library compels us to improve the material aspects of the classification originally adopted by the Museum,”16 thus implying that “before any arrangement on a methodological or geographical basis should be made, […] the photographic prints held by the photo library [had to be] classified” according to three categories:

1.Photographs that are exclusively owned by the museum: Fund(s) of the museum and of the Museum of Natural History

2.Photographs that are loaned to the museum: Copies cannot be made or sold by the commercial department outside of the museum

3.Prints made by the museum’s photo department (Service Photo-Musée): Copies can be made for free when used within the museum, while a specific contract will be made for their sale; the use of these photographs will be a source of revenue for the museum (expected profits: 50/50)

These three categories summarize the various modes of reproduction and diffusion modalities of the images in the museum’s fund. Photographs that were owned by the institution (1) coexisted alongside others that were only temporarily loaned to it and could not be distributed outside the institution (2). There was even a third and more complex category: some authors put their photographs under a contrat régie: this “specific contract for sale,” which was being drafted at the time—a point to which we shall return—, stipulated that the museum managed the prints but had to give half of the royalties to the owner of the copies sold (3).

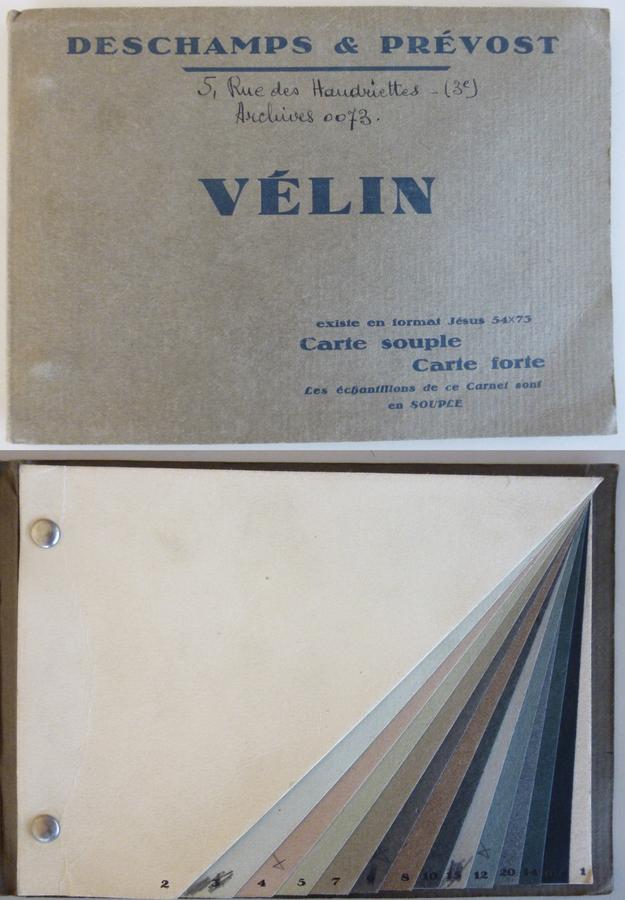

Following Montault’s first project, these three categories would have been embodied materially in the mounts on which they were fixed. Montault wrote that “in order to distinguish these prints [with distinct commercial statutes], they need to be pasted on cards of different colors.” In a manuscript version, he suggested that for “prints exclusively owned by the museum” (1) a “grey card” should be used, (2) for those “loaned to the museum” a “brown card,” and finally, (3) for those under contrat régie a “pink card.” He developed his plan in a typescript version dated October 15, 1938 by giving the precise references from the manufacturer’s color chart (see Fig. 4):

Preliminary steps before classification

The distinction between prints mounted on vellum cards: […] the three main categories of photographs in the new photo library’s fund shall be indicated by vellum cards of different colors

Photos owned by the museum (vellum already in use at the museum)

Photos loaned to the museum (vellum no. 4)

Photos under “contrat régie” (vellum no. 8)

Fig. 4: Sample of shades of vellum, Vélin Dechamps & Prévost, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

According to this proposal, the various commercial and legal terms for the use of images would seem to be embodied in their materiality itself, that is, the cards on which they were mounted. Before they even saw the image mounted on the card that they would pull out vertically from the filing cabinet, visitors or clients would immediately know, from the color of the card, the reproduction conditions of the image, that is, its exchange value. These different cards alone would have constituted a code that literally incorporated images, making their legal or commercial statute visually prominent, so much so that it could not be ignored.

As early as December 1938, this card system was nevertheless replaced by the blue, white, and red labels, as evidenced by an invoice dated December 7 of that year. The reasons for this were mainly practical. In addition to the material difficulties the Musée de l’Homme faced in buying enough cards, there was an interest in distinguishing between the two steps of recording the collections and then classifying them. Stickers were preferable to cards because they made it possible to dissociate the fixing of photographs and their precise classification; at the same time, they made it possible to include retroactively all the collections already mounted on cards during the early period of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (Mauuarin 2017). More importantly, these labels made it easier to handle when an image moved from one category to another: the museum was more than pleased when photographs originally under contrat régie (white sticker) were finally transferred to and owned by the institution (blue sticker).17 This materiality would eventually be adopted at the museum for over 50 years, thus validating Montault’s pioneering category of the contrat régie: it was a key element of the museum’s organization, which undoubtedly contributed to the Photothèque’s success and its collaborative dimension.

12.2 The Photothèque as an agency

With the three-color code first inscribed in the cards and later in the stickers, the museum gave photographers recognition of their authorship in a very material and concrete way. The former Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro had already paid specific attention to photographers, whether amateur or professional, whose work had been displayed in a temporary exhibition between 1933 and 1935 (Mauuarin 2015). Several members of the photo agency Alliance Photo, such as Pierre Verger, René Zuber, and Pierre Boucher, collaborated closely with the museum and with Georges Henri Rivière and must have helped draw attention to the issue of copyright, photographers still then largely being denied their rights by press agencies (Denoyelle 1997, 58–63).18 Estelle Blaschke even speaks of a “culture of disregard” at the time: publishers and image sellers systematically showed contempt for the emerging rights of those who took pictures (Blaschke 2011, 45). In France, only the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works19 stressed the importance of granting photographers copyright ownership, with no binding effect, however.20

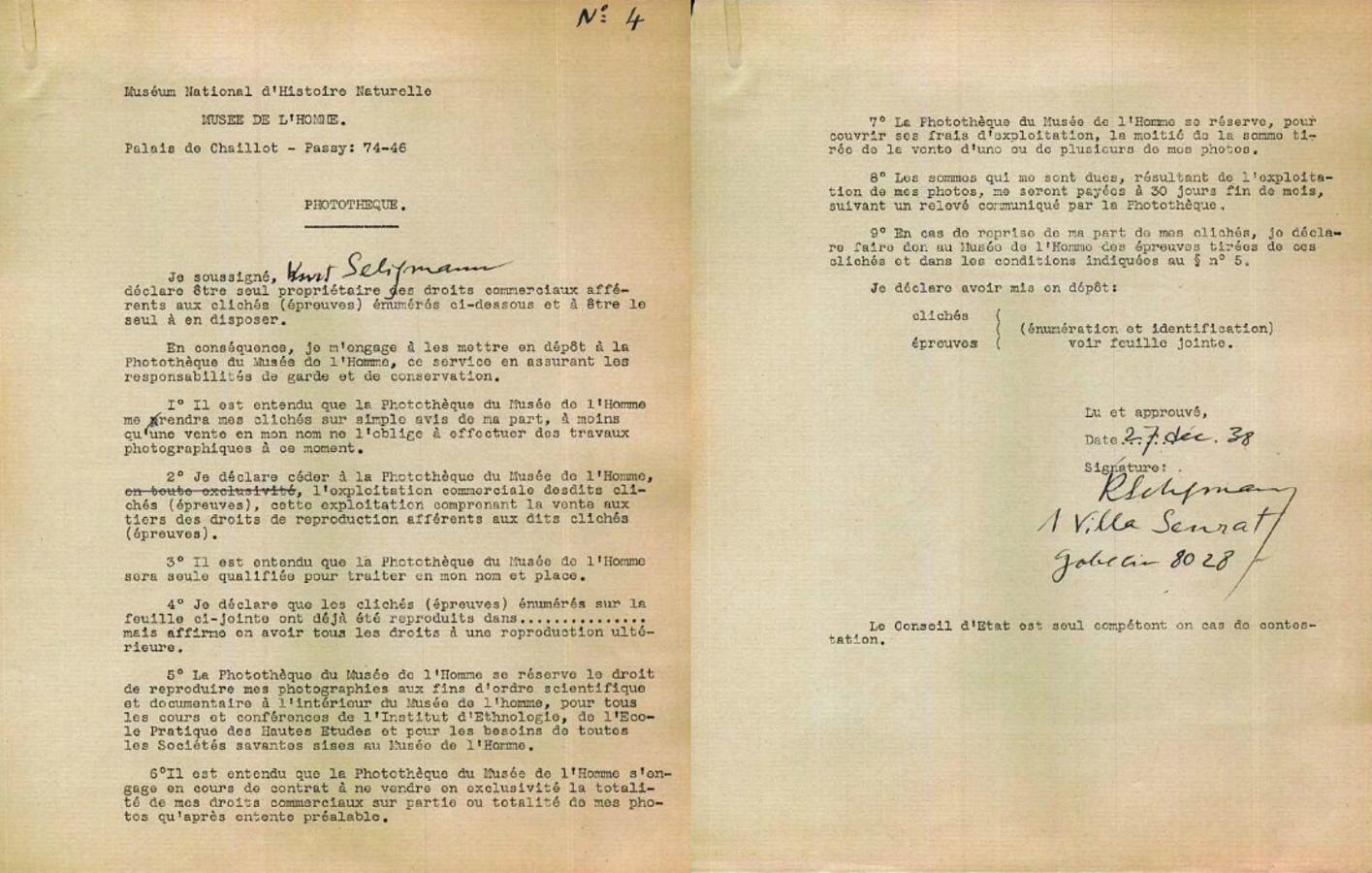

Fig. 5: Contrat-régie (specific contract for sale), between the Musée de l’Homme and Kurt Seligman, December 27, 1938, two pages, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

Therefore, members of the Photothèque can be seen as pioneers when they put in place a contrat régie in 1938 (see Fig. 5). Not only did it turn the photographer—designated as the “owner of commercial rights”—into a contracting party, but it also, and more importantly, compelled the museum to pay him or her royalties “resulting from the commercial use of [his or her] photographs” (point 8). The Photothèque thus took on an intermediary role similar to that of a photo agency: photographers entrusted it with managing their photographs, from their preservation to their distribution and sale. The Photothèque set up a system of collection by author: a series number was attributed to “each contributor or individual under a contrat régie” and “did not change regardless of the year of entry of prints or plates.”21 Collection no. 21, for example, is that of Pierre Verger, no. 33 of Henry de Monfreid, no. 41 of Marcel Griaule, etc., with the numbers more or less following the inventory order.22 The collection number was then included in the identification number inscribed on each photograph,23 thus making it easy to trace them and to ensure due payment of copyright fees.

The contrat régie, which was very favorable to photographers, and the collection system then put in place, were a way to satisfy Paul Rivet’s wish to “engage the museum’s collaborators”24 so that they would give their photographs to the Photothèque. This institution would promote images by ensuring their material protection and control,25 and by selling them, while authors could expect benefits in return. Such incentives, which were not unattractive, worked as a lever to expand the museum’s photographic collections: they were always geographically incomplete in the eyes of the Photothèque staff, who favored comprehensiveness. Two complementary logics were at work here, one scientific and the other commercial, both founded on the need to possess as many images as possible. The Photothèque wanted to have it both ways and to this end created the contrat régie, which gave its staff some leverage to negotiate with photographers: it allowed the Photothèque to attract beyond the circle of its most “willing” collaborators (bonnes volontés) who were already convinced of its scientific mission (Institut français d’Afrique noire 1953; Blanckaert 2001; L’Estoile 2005).

While this contract and the collections put photographers’ authorship at the heart of the Photothèque’s organization, the general arrangement of the prints remains paradoxically obscure. Collections were in fact classified in the filing cabinets according to geographic and ethnic categories that took no consideration of the place or the date these pictures were taken (Barthe 2000). The cards themselves rarely provided the photographer’s name. On the vast majority of these pictures, only the collection number made the link with the author and was a very indirect way for visitors and clients to have access to this information.26 Despite the attention that the Photothèque paid to authors and the museum’s interest in photographers, the materiality of images tended to obliterate their names, to hide them from the view of visitors and clients. It suggests that a name was not yet a sales argument; cards instead emphasized the availability of images.

12.3 Making images available

Alongside its activities as an agency, the Photothèque of the Musée de l’Homme wanted to make its images available: its objective to expand its collections went hand in hand with an ambition to distribute photographs beyond the research community and specialists in the field. In this regard, the department went a step further than the project of the Musée du Trocadéro in 1932, where the “photographic documentation room” was mainly designed for the museum’s staff and specialists and, in some cases and “upon justification, for a restricted audience.”27 In contrast, the 1936 project of the Musée de l’Homme included a “large reading room […] accessible to the public.”28 Archives related to its operations do not mention any registration book; reports, though not exhaustive, refer to a number of “visits”: visitors seemed to have been able to come and go as they pleased. In addition to specialists and researchers with appointments, a whole range of other people representing potential clients would also have had access to the collections.29

The white, blue, and red code was essentially intended for an external audience; its function was to provide information on the terms of reproduction of images in printed publications or other commercial media.30 Odet de Montault added other details about the material conception of the cards, which increased the availability of images: viewers could think of ways of mounting photographs on other supports accompanying or illustrating other discourses. Montault came up with two ideas which underline the standardization of images and keep their contextual singularity at a distance.

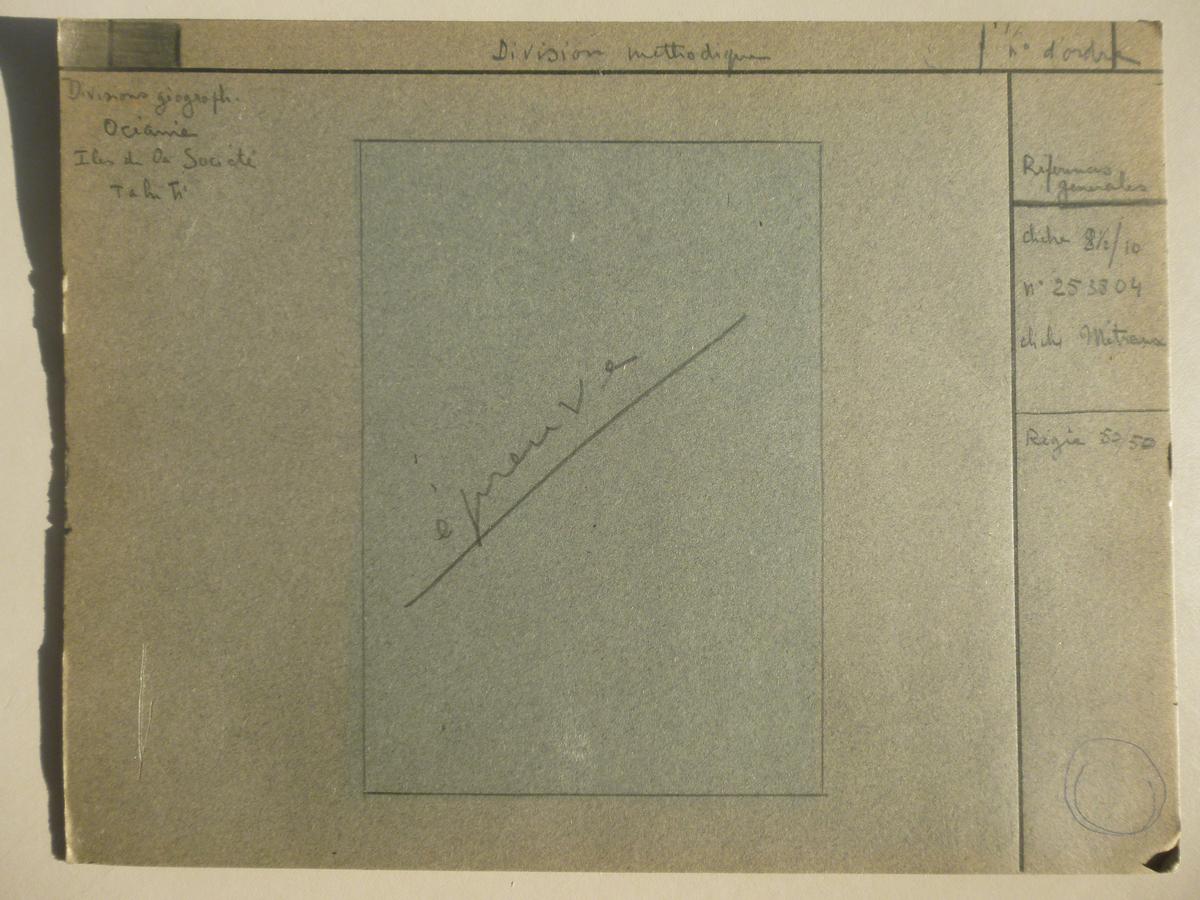

First, according to Montault’s more sophisticated project, the caption was no longer to be included beneath the image but “written on the back of the vellum,” that is, on the reverse of the card (see Fig. 6). It became impossible to view both the image and its caption at the same time: it was now necessary to turn over the card to move from one to the other. Although indications regarding the general geographical classification remained visible, information on what was represented was physically hidden behind the image, which, when extracted from the filing cabinet, seemed at first sight to be deprived of any caption. In addition to this process of partial decontextualization, Montault insisted that prints mounted on cards should all be of the same standard size, and he even recommended that “large existing formats should be printed in a smaller format.” He designed a model card (see Fig. 7) of a landscape format and in the center of this he drew a slightly colored rectangle where the “print” was to be mounted. This rectangle of a portrait format suggests that Montault wanted all prints to be immediately “decipherable” without visitors or clients having to rotate the card, which means that some images had to be reduced to be viewed properly.

These two propositions, the first—the disappearance of the caption—being adopted only temporarily,31 map out the contours of a method of looking at photographs promoted by Montault that neutralizes both the original material history of photographs and their connection with the context and the specific narrative of when they were taken. A similar process of decontextualization of photographic collections had already been initiated in 1935 at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge: images accumulated since 1884 had been reprinted and mounted on cards alongside an individual file compiling all the corresponding captions, which were thus also separate from the images (Boast, Guha, and Herle 2001, 3). According to Elizabeth Edwards, this “regularity of the physical arrangement of image[s]” reinforced the “taxonomic readings” of images and their “visual comparability,” thus creating “a cohesive anthropological object” (Edwards 2002, 71). In his project, Montault presented a similar process of standardization and homogenization, even if it was developed from a commercial perspective before becoming a scientific project.

Fig. 6: Cardboard pattern, verso, Odet de Montault, October 1938, 22.5 x 29.5 cm, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

Fig. 7: Cardboard pattern, recto, Odet de Montault, October 1938, 22.5 x 29.5 cm, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

The standardization of prints as well as the visual dissociation of the image and its caption, which still remains an enigma in the case of the Cambridge museum,32 aimed above all at creating optimal conditions for viewing these prints, which provided little information in a fairly simplified fashion, like images that visitors could imagine inserted in various visual contexts, media, and discourses. Formatting and isolating images contributed to keeping at a distance what Edwards has called their “own semiotic energies” (Edwards 2002, 71) and what Walter Benjamin would have described as their “presence” (or hic et nunc) (Benjamin 2008). These material modalities also provoked a distancing of the actual referent (Kracauer 1995; Sekula 1981); articulated through the color code informing visitors about the exchange value of images, it reinforced the ability of images to circulate and be exchanged, thus turning them into commodities.

12.4 The meaning of collections in economic terms

The fact that images were materialized and made available through colors and cards invites us to return to our analyses of the general organization of the Photothèque. The choice of a geographical area division can indeed correspond to different goals: if those boundaries reflected the organization of French ethnology and, more specifically, that of the museum (Barthe 2000), they also appeared to meet the needs of clients who were particularly interested in what Jacques Soustelle dubbed “geographical news” (l’actualité géographique).33 The choice of colors associated with each continent34—black for Africa, red for South America, yellow for Asia, etc.—referred to a popular vision of races, thus easily recognizable. A later element that reinforced the availability of images is a file classifying images by subject matter (fichier-matière) created in the early 1940s. Visitors could then search the photographic collections by theme rather than by geographical area.

Through the case study of Montault’s project and the background of the constitution of the photographic collections of the Musée de l’Homme, it becomes impossible to favor one epistemological analysis over another in order to understand the various tools put in place to manage the photographic collections. Although these various tools all help turn photographs into visually comparable elements that could meet the potentially scientific uses of images35 and consequently create an “anthropological object,” sources and uses reveal that an analysis of this type needs to be reevaluated and that special attention must be paid to the economic objectives and aspects of photographic collections. Therefore, the analysis of scientific and documentary collections must be combined with a more economic approach that is more common when dealing with photo agencies. In addition to the Musée de l’Homme, several French scientific institutions had a commercial department within their photo libraries or photographic departments: this applies to, for example, the Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient in the 1930s,36 or the Institut français d’Afrique noire from the 1950s onward (Touré 2000). Does this mean that, from the 1930s onward, the objectives behind these large photographic collections were no longer strictly scientific?

If the Musée de l’Homme had indeed earned its place among major scientific institutions,37 the commercial department of the Photothèque had also become prominent in the landscape of photo agencies. The Photothèque’s staff in fact clearly referred to it as a photo agency and compared it to others in existence at the time.38 Consequently, we need to redefine the logic of image accumulation, which remained an explicit goal of both the Photothèque and other institutions mentioned above. Whereas at the end of the nineteenth century, as shown by François Brunet and Elizabeth Edwards, scientific and anthropological institutions collected and arranged photographic collections to enhance their scientific authority (Brunet 1993; Edwards 2001), similar practices took on a very different meaning in the 1930s: for institutions such as the Musée de l’Homme, they represented opportunities to establish themselves as authorities and economic powers. The challenge was now to make a difference in the market of images.

Translated from the French by Camille Joseph

12.5 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Fillette Muong (Young Muong girls), Vietnam, mission Cuisinier-Delmas, Lucienne Delmas or Jeanne Cuisinier, 1937, baryte print, 10.3 x 16 cm (photo), 22.5 x 29.3 cm (cardboard), Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, inv. no. PP0005858.

• Fig. 2: Salle de travail de la Photothèque (Working room in photo library), Musée de l’Homme, Diloutremer, c. 1950, baryte print, 22.5 x 29.5 cm (cardboard), Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, inv. no. PP0090871.

• Fig. 3: Code de signalisation visuelle des documents (Color code for documents), Lucienne Delmas, c. 1950, 2 pages, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

• Fig. 4: Sample of shades of vellum, Vélin Dechamps & Prévost, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

• Fig. 5: Contrat-régie (Specific contract for sale), between the Musée de l’Homme and Kurt Seligman, December 27, 1938, two pages, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

• Fig. 6: Cardboard pattern, verso, Odet de Montault, October 1938, 22.5 x 29.5 cm, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

• Fig. 7: Cardboard pattern, recto, Odet de Montault, October 1938, 22.5 x 29.5 cm, Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Photo Library Archives.

12.6 References

Barthe, Christine (2000). De l’échantillon au corpus, du type à la personne. Journal des Anthropologues 80–81. (Question d’optique):71–90.

Benjamin, Walter (2008). The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproductibility and other writings on media. Ed. by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge (Mass.) and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Blanckaert, Claude, ed. (2001). Les politiques de l’anthropologie : discours et pratiques en France, 1860–1940. Paris: l’Harmattan.

– ed. (2015). Le Mus ée de l’Homme : histoire d’un mus ée laboratoire. Muséum national d’histoire naturelle/Editions Artlys.

Blaschke, Estelle (2009). From the Picture Archive to the Image Bank. É tudes photographiques 24: 150–181. url: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3435 (visited on April 12, 2017).

– (2011). Photography and the Commodification of Images: From the Bettmann Archive to Corbis (1924–2010). PhD thesis. Paris: EHESS.

– (2016). Banking on Images: The Bettmann Archive and Corbis. Leipzig: Spector Books.

Boast, Robin, Sudeshna Guha, and Anita Herle (2001). Collected Sights: Photographic Collections of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1860s–1930s. Cambridge: Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology.

Bouillon, Marie-Ève (2012). Le marché de l’image touristique. É tudes photographiques 30. url: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3334 (visited on April 12, 2017).

Brunet, François (1993). La Collecte des vues: explorateurs et photographes en mission dans l’Ouest am éricain. PhD thesis. Paris: EHESS.

Business mit Bildern: Geschichte und Gegenwart der Fotoagenturen (2016). Fotogeschichte 36(142).

Daston, Lorraine and Peter Galison (2007). Objectivity. New York: Zone Books.

Delpuech, André, Christine Laurière, and Carine Peltier-Caroff, eds. (2017). Les Années folles de l’ethnographie: Trocad éro 28–37. Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle.

Denoyelle, Françoise (1997). La lumi ère de Paris. Tome 1: Les usages de la photographie. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Dias, Nélia (1991). Le Mus ée d’ethnographie du Trocad éro (1878–1908). Paris: CNRS.

Edwards, Elizabeth, ed. (1992). Anthropology and Photography, 1860–1920. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

– (2001). Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. Oxford and New York: Berg.

– (2002). Material Beings: Objecthood and Ethnographic Photographs. Visual Studies 17(1):67–75.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Sigrid Lien, eds. (2014). Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs. Farnham: Ashgate.

Fabian, Johannes (1983). Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Frizot, Michel and Cédric de Veigy (2009). Vu : le magazine photographique, 1928–1940. Paris: Ed. de La Martinière.

Frosh, Paul (2003). The Image Factory: Consumer Culture, Photography and the Visual Content Industry. London / New York: Berg.

Institut français d’Afrique noire (1953). Institut fran çais d’Afrique noire: Instructions sommaires. Dakar: IFAN.

Kracauer, Siegfried (1995). On Photography. In: The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. Ed. by Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge (Mass.) and London: Harvard University press.

L’Estoile, Benoît de (June 2005). Une petite armée de travailleurs auxiliaires. Les Cahiers du Centre de Recherches Historiques. Archives 36. url: https://journals.openedition.org/ccrh/3037 (visited on April 12, 2017).

– (2007). Le Go ût des autres: de l’Exposition coloniale aux arts premiers. Paris: Flammarion.

Lacoste, Anne, Olivier Lugon, and Estelle Sohier, eds. (2017). Musées de Photographies Documentaires: Introduction. Transbordeur 1:8–17.

Laurière, Christine (2008). Paul Rivet: le savant et le politique. Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle.

– (2015). 1938-–949: Un musée sous tension. In: Le Mus ée de l’Homme: Histoire d’un mus ée laboratoire. Ed. by Claude Blanckaert. Paris: Muséum national d’histoire naturelle/Editions Artlys, 46–77.

Mauss, Marcel (1947). Le manuel d’ethnographie. Paris: Payot.

Mauuarin, Anaïs (2015). De « beaux documents » pour l’ethnologie. É tudes photographiques 33:21–41. url: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesphotographiques/3559 (visited on April 12, 2017).

– (2017). La Photographie multiple: Collections et circulation des images au Trocadéro. In: Les Ann ées folles de l’ethnographie: Trocad éro 28–37. Ed. by André Delpuech, Christine Laurière, and Carine Peltier-Caroff. Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle.

Mitman, Gregg and Kelley Wilder, eds. (2016). Documenting the World: Film, Photography, and the Scientific Record. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Peltier, Carine (2007). L’iconothèque du musée du quai Branly. Bulletin des bibliothèques de France 4:10–11.

Sekula, Allan (1981). The Traffic in Photographs. Art Journal 41(1):15–25.

Touré, Khady Kane (September 2000). Pour valoriser les fonds de la photothèque de l’IFAN. Documentaliste, Sciences de l’information 37(3–4):174–181.

Footnotes

This new photo library was created when the Musée de l’Homme opened in Paris. The museum was officially inaugurated on June 20, 1938 as a substitute for the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. On the history of the new museum, see L’Estoile 2007; Laurière 2008; Blanckaert 2015. On the Musée du Trocadéro in its early days, see Dias 1991, and for the transition period, with the arrival of Paul Rivet and Georges Henri Rivière as its directors (1928–1935), see Delpuech, Laurière, and Peltier-Caroff 2017.

Since the 1990s, this new approach has found its way into the history of photography, as demonstrated by the introduction to the first volume of the new academic journal Transbordeur, in which Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon, and Anne Lacoste insist that “materiality affects the meaning, the value and the uses attributed to photographs and their performativity” (Lacoste, Lugon, and Estelle Sohier, eds. 2017, 10).

See, for instance, the works of Paul Frosh (2003) and, with a more historical perspective, those of Marie-Eve Bouillon (2012) and, more importantly, Estelle Blaschke (2009; 2011; 2016). On photo agencies and image banks, see a recent volume of Fotogeschichte, “Business mit Bildern. Geschichte und Gegenwart der Fotoagenturen” (2016).

The above-mentioned volume of Transbordeur indeed suggests that such a division existed in 1885–1905. While the first few lines of the introduction rightly point out that “at the end of the nineteenth century […] new means of photomechanical reproduction led to a growing number of cheap illustrations in increasingly numerous printed material,” the volume does not tackle the issue of the commercial circulation of images but instead independently treats the question of the deep changes affecting image collections in “heritage institutions, museums, archives and libraries” (Lacoste, Lugon, and Estelle Sohier, eds. 2017, 9).

This phenomenon was by no means specific to photography but was in fact a common imperative for all object collections in the museum, completely in line with the importance attached at the time to the ethnological study of material culture. On this aspect, see L’Estoile 2007. On the notion of “collaborator,” which I shall later turn to, see L’Estoile 2005.

These archives consist of three boxes containing various types of material with no clear order. Among them are plans for the organization of the photo library, on which this paper relies in particular, as well as Activity Reports covering at least the period 1938–1960. Here, we refer to the original number of the boxes. However, because this fund is currently being reorganized, call numbers are likely to change soon.

Son of the marquis de Montault, Odet de Montault was 29 years old in 1938 when he joined the museum staff. Jacques Soustelle immediately put him in charge of the constitution of the commercial department. But he did not stay at the museum long: he was mobilized during the war and then resigned in October 1945. He nevertheless left a deep impression on the department and his collaborators, as evidenced by some very warm letters, for instance those from André Leroy-Gourhan (Bibliothèque Centrale du Muséum/Archives of the Musée de l’Homme (further cited as: BCM/Archives MH)/2 AM 1K 67c).

This transfer has produced a large body of literature. On photographs, see Carine Peltier’s note (Peltier 2007).

Collaborating with the Asian Department at the Musée du Trocadéro, Lucienne Delmas made this field trip in 1937–1938 with Jeanne Cuisinier; they brought back numerous photographs (BCM/Archives MH/2 AM 1M1d). Lucienne Delmas became officially in charge of the Photothèque of the Musée de l’Homme in 1938 (BCM/Archives MH/2 AM 1D2) and progressively became its most prominent figure until the 1950s.

The final arrangement of the Photothèque originally included four main categories: ethnology, (physical) anthropology, palaeontology, and archaeology. In reality, photographs belonging to the “ethnology” category were by far the most numerous, thus echoing the museum’s priority which, even though it was a “museum of man” and not only a museum of ethnology, gave preeminence to the discipline (Laurière 2015).

In the final version adopted by the museum, there was a black tab for Africa, yellow for Asia, red for South America, pink for North America, etc. This color code finds its origin in the racial classification presented by Carl von Linnaeus around 1758 in the second edition of his Systema Naturae. In 1938, however, the plan designed by Odet de Montault was somewhat different: white Africa was green, America grey, Asia orange, Oceania red, while black was already referring to black Africa.

These tabs are of the Flambo brand; tabs at the top are “N°5/No. 5” and tabs at the bottom are “N°10/No. 10.”

Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (MQB)/Archives Photothèque/Box 5.

Photographs of objects were sometimes used to illustrate labels or catalogs. Field trip photographs were inserted in display cases during exhibitions in order to explain how objects were used. They were all made following a very precise model (in terms of size, caption, typography, position, etc.) (BCM/Archives MH/2 AM 1 l2). On this question, which was already at stake at the time of the Musée du Trocadéro (1928–1935), see Mauuarin 2017. More generally, on the various uses of photographs in museums, see Edwards and Lien 2014.

Cards of this size were used in the early 1930s at the photo library that was initiated within the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, replaced in 1938 by the Musée de l’Homme. On the photo library of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, see Mauuarin 2017.

Odet de Montault wrote at least four drafts of plans for the new organization of the future Photothèque. In this part of my paper, I mainly focus on two of them: a manuscript draft, which seems to be the first, and a typescript one, which appears to have been written later and is the only one to be dated, October 15, 1938 (MQB/Archives Photothèque/Box 5).

The history of the Photothèque reveals that at other times—around 1964 particularly—a number of collections originally under contrat régie were included in the museum’s funds when it appeared impossible to contact authors and update their wishes.

The 1920s and 1930s, however, witnessed a growing recognition of the work of photographers, particularly on the part of some French magazines such as Vu, which began crediting star authors (Frizot and Veigy 2009).

The Berne Convention was signed during the first conference on September 9, 1886, and then was regularly revised up until the 1970s. Photography was first mentioned in 1896 at the Paris Conference in the form of an additional act.

Until the 1957 law which, for the first time, included photographs among “works of the mind,” conditions to ensure the protection of photographs were decided by courts when necessary.

Odet de Montault, “Photothèque,” October 15, 1938 (MQB/Archives Photothèque/Box 5). Documents of the same period prepared by Lucienne Delmas contain lists of these first collections (MQB/Archives Photothèque/B4).

Numbers below 300 do not necessarily follow the chronological order in which collections were acquired by the Photothèque. After 300, they more or less reflect this order, but it remains approximate because several collections could have been deposited simultaneously, while others were put on hold for months or even years due to the lack of staff, or simply because some of them were so numerically important that they required specific means to be inventoried.

This collection number is added a posteriori to the identification number of the collections that were deposited and inventoried at the time of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, then comprising only the year followed by the collection number in the year (e.g., 33-2345). From 1938 onwards, a third digit identifying the “collection” was added: in order to avoid a complete reinventory of all the collections, this was placed after the first two and not in-between.

Jacques Soustelle, Note sur l’activité du service commercial de la Photothèque, n.d. (1939) (BCM/Archives MH/AM 1l2c).

For how the material organization of photographs may add to their value, see Estelle Blaschke’s conclusions based on Oliver Wendel Holmes’s writings (c.1857) (Blaschke 2011, 11).

There is no trace of a free-access database that would have allowed visitors and clients to find the author corresponding to each number. Such a database would have made it easier to obtain the information, while still keeping the photographer in the background.

Georges Henri Rivière, Principes de muséographie ethnographique, February 24, 1932 (BCM/Archives MH/ 2 AM 1 G2e).

Anonymous, Rapport annexe aux plans des nouvelles installations du Trocadéro, January 27, 1936 (BCM/Archives MH/2 AM 1G3d).

During the year 1946, the department dealt with many representatives from magazines such as Tourisme et travail, Sciences et voyages, Réalité, or La Marseillaise and responded to various requests, sometimes quite unusual like that of a Mr. Paul-Marguerite who was looking for a picture of the former Trocadéro to make a cul-de-lampe (G. Bailloud, Rapport du 3e trimestre 1946, MQB/Archives Photothèque/Box Prudhomme 2).

Some clients were looking for pictures, particularly of objects, to use in films. This was, for instance, the case of “young filmmakers” Zimbacca and Bédouin, who became regular visitors and clients of the Photothèque in 1951 and 1952 (MQB/Archives Photothèque/Box 5).

There are examples of this in the collections of Gaëtan Fouquet and Jacques Gruault (in particular, PP0147853 and PP0147547).

The works of Boast, Guha, and Herle, and Edwards provide no explanation for the physical arrangement of the cards, nor do they make clear how scholars used the captions written on separate files. It is highly improbable that an image with no caption could have been a satisfactory document for any ethnological research; suffice it to say that, as early as 1926, Marcel Mauss in his courses on descriptive ethnology insisted upon the importance of systematically recording the context in which the image was taken (Mauss 1947).

Soustelle, Note sur l’activité du service commercial de la Photothèque, n.d. (1939) (BCM/Archives MH/2AM 1l2c).

As Elizabeth Edwards (2002) has demonstrated in the case of the Cambridge museum, the arrangement of photographs on cards encouraged a comparative approach, which had been at work in anthropology since the nineteenth century in close connection with the treatment of images. But studies are still needed to understand the actual use that scholars made of photographs in the 1930s, which was probably of an entirely different nature.

On this photo library and the work of Jean Manikus as a photographer for the school, see the Bulletins and Cahiers de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (1931–1942).

It is worth recalling here that the museum had been under the tutelage of the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris since 1928.

The report for the fourth quarter of 1952 is explicit when Lucienne Delmas notes that the prices of the Photothèque are “slightly cheaper than those of other agencies” (MQB/Archives Photothèque/Box 5).