The chapters in this book reflect some of the papers presented at the conference on “Photo Objects,” which posed new questions, identified new concerns, made important connections, and opened new avenues to explore.1 In the range of subjects, images, and institutional practices being explored, we witnessed the diversity and reach of our field. There was both comfort and synergy in a community of scholars from different archives, different countries, and different disciplines, drawn together through a common focus on the photo-object. Papers that would have been on the margins of most conferences organized along professional or disciplinary lines were central to participants’ research agendas and scholarly interests.

In the workshop, panelists asked “uncomfortable questions”2 and presented an array of thought-provoking photo-objects (Bärnighausen et al., Chapter 2) and related scholarly concerns, as well as new ways of addressing them. Audience interventions, questions, and observations contributed enormously to rich and productive discussions, and, certainly, it was a stroke of genius to bookend Elizabeth Edwards (Chapter 3) and Lorraine Daston (Chapter 4) as the two keynotes. In the past, their work forced us to think about photographs in terms of materiality, on the one hand, and objectivity, on the other; here, the former used the notion of “non-collections” and the latter pinpointed “archival moments in the sciences” as ways to challenge and expand our investigations of photo-objects.

We were also introduced to the Photothek of the Kunsthistorische Institut in Florenz—Max-Planck-Institut by Costanza Caraffa and Julia Bärnighausen, who explained its aims, structure, and procedures, and shared some of its treasures and tales. Surrounded by boxes of card-mounted photographic copies of works of art, organized and labeled in a particular way, we were alerted, in demonstrable ways, to some of the idiosyncrasies of photographic archives and the challenges they pose for researchers.

We have seen striking images—from a late nineteenth-century card-mounted print of a row of jars of tumours (Zeynep Çelik, Chapter 8), reminiscent of William Henry Fox Talbot’s Articles of Glass, to a large backlit transparency from Catherine Yass’s Corridors series (Haidy Geismar and Pip Laurenson, Chapter 10). We were introduced to a wide array of archives, collections, and albums (Lena Holbein, Chapter 13), presented with curious images, and confronted by disturbing issues. Speakers presented important observations and nuanced critiques on multiple originals, “duplicates,” and copies (Petra Trnková, Chapter 14). Audience attention was drawn to photographic effect and affect, to collections and non-collections, to archival ecosystems, moments, and afterlives.

Colonialism, displacement, and identity were themes that threaded through a number of papers, revealing links across widely divergent topics and offering insights into lingering problems. Focus on the nature, meaning, and power of photo-objects brought coherence to research in a wide variety of disciplines, including anthropology (Christopher Pinney, Chapter 11), archaeology, astronomy (Omar Nasim, Chapter 9), medicine, politics, and commerce (Anaïs Mauuarin, Chapter 12), and to inquiry into museums and science; archives as institutions and archives as evidence; duplicates and slides (Maria Männig, Chapter 16); cataloging and communication. Kelley Wilder (Chapter 15) touched on the relationship of word to image. Equally powerful, if less obvious, were the themes of invisibility, recuperation, and repurposing. Addressed directly by Lorraine Daston, but in many ways quietly permeating the overall topic of the conference, was durability—durability of substance, durability of meaning.

Underpinning all papers was a fluid, sometimes amorphous understanding of the term “archives”—highlighting the basic question: “What do we mean when we speak about the archive or archives?” The word itself is not used consistently. There are academic and theoretical as well as professional and institutional understandings of the archive(s) as: cultural institution, documentary accumulation, authored inventories, artificial collections, metaphorical construct. What, then, is our understanding of photo archives? Is it Costanza Caraffa’s Photothek of the art historian (Chapter 1), from which Katharina Sykora analyzed a compelling series of photographs entitled the “Triumph of the Photography” (Chapter 7)? Or the glass plate negatives of Lorraine Daston’s astronomers, the family photographic archives of Suryanandini Narain, the “affective archives” of Vered Maimon,3 the dispersed Ataturk archives of İdil Çetin (Chapter 5), the medical research archives of Zeynep Çelik (Chapter 8), or the archaeological archives of Christina Riggs (Chapter 17)? The archives addressed by the conference speakers share certain assumptions, structures, and features that make them “archives” in the scholarly imagination, but each has its own story to tell of accumulation and mandate, people and place, ideological constraints and social power. And therein lies the slippage that complicates our understanding of the nature and role of photo archives.

If the papers revealed the many ways in which “archives” are constituted and understood, less was said about the role of the archivist—in deciding what is preserved and in determining what is made available and how. There were references to “completeness” and, yet, archives are never complete. They are seldom whole and never inert; they are formed and re-formed, added to incrementally, culled, reorganized, described, reformatted, repurposed. This remains a key topic for future discussion.

“In the archives, a thousand photos that detail our questions” (Hunter 2004, 94). This line from a poem by Aislinn Hunter entitled “The Interval” flags an issue central to the study of photo-objects and photo archives. In citing it, I run the same risk as presenting a quote—or taking a photograph—out of context. But this line, for me, epitomizes a problem endemic to the scholarly use of photographs, particularly those preserved in archives. Researchers enter archives with questions in search of answers. Far too often, they are looking for a photograph of something—a person, a place, an event, a thing—to corroborate or illustrate their research findings. Far less often, they look at photographs, not for the answers they supply but for the questions they pose. This line of Hunter’s resonates with Thomas Schlereth’s observation that questions posed by historians “have usually not been phrased in ways that photographic data can answer” (Schlereth 1980, 15).

It is, therefore, not enough simply to reformulate our questions or expand the range of queries we pose. Rather, in delving into the social biographies of images, it is also necessary to be more attentive to the questions that photographs ask us, if only we are prepared to listen to them. To track changes in the meaning(s) of photographs as they come down to us across time and space—as scholars, as historians, as archivists— we must study photographs for the critical roles they play in the processes by which individuals and societies communicate and remember.

To do so requires that we change the relationship we have with photographs. Users and keepers of archives can no longer merely ask what photographs are of, naively conflating content and meaning. Rather, they must push beyond visual content to explore content in context, to shift attention from indexicality to instrumentality, to ponder what photographs are about, consider what they were created to do, reflect on how they circulated, contemplate what meanings they generated, muse upon what actions they prompted, uncover the effects they produced—at different times of their social biography. We need to foreground assumptions that underpin the ways in which photographs are digitized, published, or otherwise repurposed and recirculated—how their material nature is obscured or altered, and, consequently, how the relationships embedded in them change, why, and to what end.

Historians, archivists, curators, and librarians ask questions that variously reflect professional perspectives, disciplinary expertise, and institutional mandates. Their questions privilege and marginalize in different ways, shaping the meaning of photographs in ways that are both subtle and profound. What is important to acknowledge here is that archives are fundamentally different from other heritage repositories in their mandates and methods, approaches and patrons, their questions and their answers. That archives keep records in a particular way for a particular reason is critical to understanding the place of photographs in archives, how to find them, and what they mean there.

Our speakers have demonstrated the importance of theoretically informed but empirically grounded photographic research. Theory-driven research is self-fulfilling. Those in the audience who have worked as archivists or collections managers or have immersed themselves fully in archival collections know all too well that enthusiastic scholars inclined to impose theory on photographic archives can always find images to support their arguments. But are these images typical or unique, original or copy? For those with just a little more patience, a lot more digging, and a smattering of photo history, do they, in fact, undermine the very premise that they were chosen to reinforce visually? It is clear that the speakers here have gone into the archive prepared to let photographs pose questions. Those questions are not necessarily questions that can be answered directly from photographs themselves. Those questions may send us off on a wild goose chase, into the documentary universe in which photographs circulated—racing down dead ends, lured by red herrings, and tumbling headlong into the ecosystem and non-collections that Elizabeth Edwards described.

Several key topics were touched upon obliquely or in passing: copyright, for example, a topic almost impossible to discuss at an international gathering, except in theoretical or the most general of terms, since copyright laws vary dramatically from country to country. More universal and pressing, however, is the impact of electronic communication on copyright laws governing the reproduction and circulation of photographs and born-digital images.

In her keynote, Lorraine Daston drew attention to durability as an assumption of the archive, pointing to assumption for the longevity of ancient inscriptions on paper squeezes and a map of the heavens on glass. The durability of the unexpected—of paper and glass over stone—points to contemporary archival concerns about longevity of born-digital images in an age of electronic communication and preservation. However, the elephant in the room was not the born-digital image but digitization, by which I mean the processes and consequences of scanning analog photo-objects, attaching metadata, and making surrogates available online. Mentioned more than once in passing, it is a topic that warrants close consideration by users of archives because of the capacity of creators and keepers of archives to efface and/or emphasize elements of photographic meaning-making in the dematerialization and decontextualization that so easily occurs, often inadvertently. This concern brings us full circle back to the power of archivists and others who are responsible for determining the value of images, ensuring their preservation, and providing access to them. In questioning where, how, and by whom the value of the photo-object is assigned, we tackle thorny assumptions about the nature of value as inherent or contingent, and about hierarchies of value.

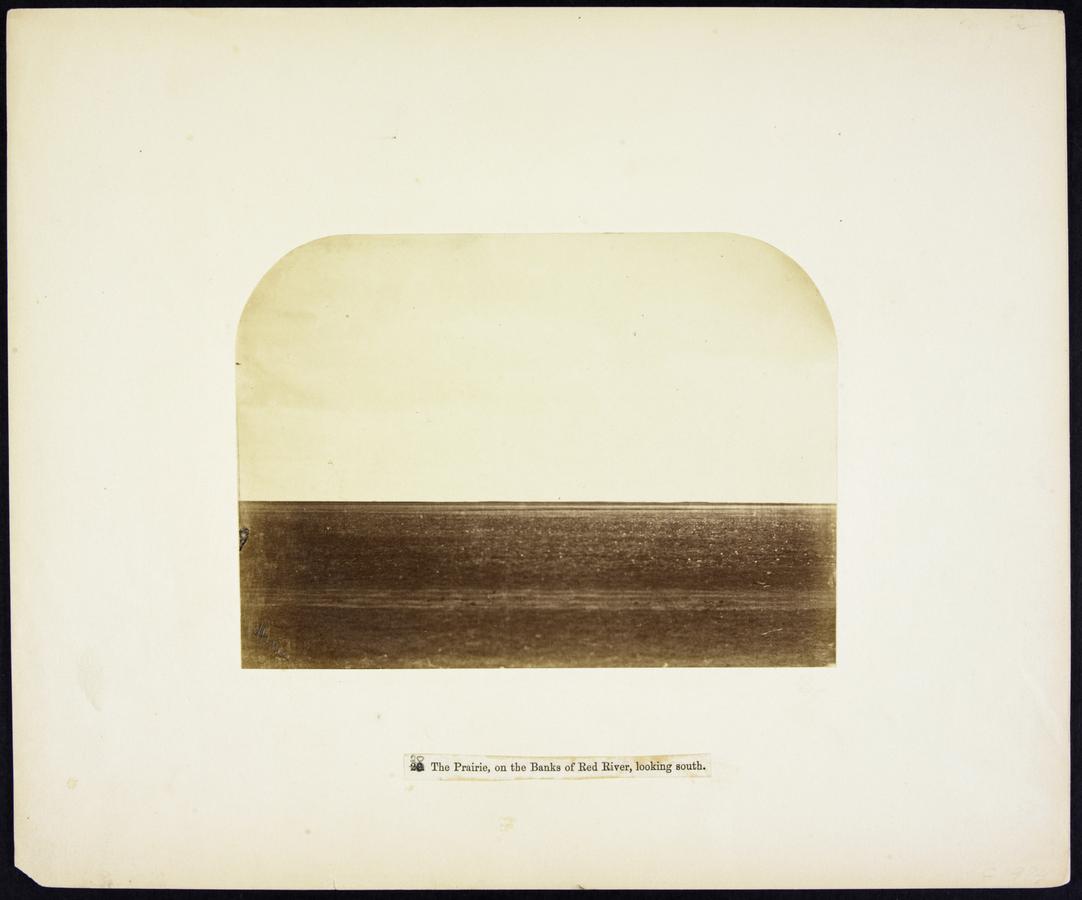

Fig. 1: Humphrey Lloyd Hime, The Prairie, on the Banks of Red River, looking south, September–October 1858, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1936-273, copy negative # C-018694.

Whereas many of our speakers amply illustrated the importance of photographic evidence by elaborating on the historical significance of visual facts and sometimes obscure or minute details, some photographs are significant for what cannot be seen at different registers. Let me call upon three examples to elaborate on this point. It is easy to assume that Humphrey Lloyd Hime’s The Prairie, on the Banks of Red River, looking south (see Fig. 1)4 is an image of barren desolation. The key aspect of its visual content, in fact, has no visible presence: it is a photograph of “treelessness.” For much of the nineteenth century, the assumption was that an absence of trees in a landscape signified aridity and a lack of agricultural potential. This stood as a critically significant barrier to dreams of westward territorial expansion on the North American continent. But this assumption had a timeline that took a dramatic U-turn in 1856 when scientific findings on the climatology of the United States disrupted the notion of the Great American Desert5 (Blodget 1857, viii). By the time this photograph was taken, assumptions about barren desolation had given way to an Edenic vision of a transcontinental nation. What is missing from Hime’s quintessential image of the prairie was a litmus test; the “of-ness” of the photograph was interpreted very differently after new knowledge generated new expectations in what viewers brought to the act of looking.

Fig. 2: [William England] London Stereoscopic Company, The Suspension Bridge, Niagara, 1859, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1988-286, copy negative # PA-165997.

Similarly, in William England’s 1859 photograph of the Niagara Suspension Bridge (see Fig. 2)6 the international border runs invisibly and significantly down the middle of the river, bisecting the bridge and the train which straddles two countries. It is a record of what David Nye has called “the American technological sublime” (Nye 1994). In the distance, embedded in the stratigraphic layers of the Niagara Gorge, nineteenth-century viewers would have seen the controversies, generated by the work of Charles Darwin on evolution, Charles Lyell on geological time, and Bishop Ussher on the date of creation of the universe, collide. Ideas about engineering, progress, biblical truth, and scientific knowledge defined this image’s “about-ness”—ideas brought to the act of looking by Victorian viewers, ideas not obvious to twenty-first-century eyes.

Such photographs by Hime and England are examples of temporally distanced images, the rhetorical power of which cannot be fully appreciated—or understood—without historical contextualization.7 But what of more contemporary photographs, the kind we see on a daily basis in newspapers, on billboards, and in magazines? Do we stop to consider the tacit but powerful messages they carry about our society, its beliefs and values? Before the internet flooded our quotidian spaces with photographs, the National Archives of Canada mounted a small display of fashion photography by noted Toronto photographer Struan Campbell-Smith. The large colour prints were matted and framed, and, as such, were divorced from the advertising copy that otherwise normalized—or distracted from—their visual content. Not surprisingly, several photographs showed women scantily clad or provocatively posed.

A controversy erupted over the show, prompting a heated letter from one irate researcher who complained about the display of “pornography” on the walls of an institution dedicated to "high culture". One photograph, created for the Quinto shoe company for advertising purposes, showed a naked female torso bent in silhouette over a high-heeled shoe (see Fig. 3).8 It was stolen twice, perhaps a measure of its popular appeal. What was both striking and illuminating was the way in which the exhibition’s critics, surprised to find sexualized images of women in the corridor between the reception desk and the cloakroom, failed to look beyond the visual content of Struan’s work.

Fig. 3: Struan Campbell-Smith (Toronto), Red Shoe, 1977, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1980-193, copy negative # PA-181604, courtesy: Struanfoto, Toronto.

The Struan Campbell-Smith photograph, like the Hime and the England, is an image made meaningful by what we bring to the act of looking. When seen in an advertisement in a magazine, on a billboard, or in a bus shelter, surrounded by the advertising copy that supplies its functional context, the image becomes banal, its power dissipated by its placement in socially accepted—or ignored—visual circumstances. But, stripped of its advertising copy and viewed matted, framed, and decontextualized in a place usually reserved for benign, presumably neutral and objective, historical documents, the Quinto shoe photograph was seen afresh, stark and unencumbered by words.

The portfolio of Struan’s fashion photography held up a mirror to advertising images employed to sell everything from women’s shoes to car mufflers. Displayed large and out of context, his Quinto shoe photograph is a perfect study in layered looking. One can ask: What is it of? What is it about? What was it created to do? On the surface, the photograph is of a naked woman bent over a shoe, but the Archives did not acquire the image to document the corresponding curvature of a 32A breast and a 6B stiletto shoe. Returned to the circumstances in which it was intended to be seen, the photograph is about sex and the exploitation of women in advertising. This points to its functional context of creation: the photograph was created to do something—to sell shoes.

Carrying reaction to its logical conclusion, why shoot the messenger? The wrath of critics was not leveled at the shoe industry for promoting ergonomically unsound footwear, nor at the advertising industry for using sexualized images of women to sell products (in this instance, at least, it was women’s shoes and not car mufflers), nor at the publishing industry for accepting and circulating advertisements that reinforced societal approbation of sexual innuendo and gender bias. Rather, the institution where the work was exhibited was censured for displaying the Struan photograph in its front corridor. The irony was not lost on photo archivists.

Hime’s print, England’s stereoscopic view, and Struan’s advertising image also flag how the act of looking is governed by the photo-object’s presentational form. Where cataloging information often includes dimensions, the weight of a large, leather-bound album is not usually part of a conservation treatment report or a descriptive record, and yet weight offers clues to the way in which the photographs contained in a heavy album were stored, displayed, and viewed. The “albums” created on our cell phones and computers are the antithesis of the cumbersome, leather-bound volumes with gilt and gauffered edges, marbled endpapers, and silk headbands, all of which framed the act of looking and contributed to the meaning of the photo-object.

After two and a half days of intriguing papers that plumbed the depths of form and format, materiality, and meaning, I am inclined to ask what transformations take place when the digital surrogate not only becomes accepted as a way to preserve the original, reduce on-site access, and provide online access, but is also embraced as an aesthetic substitute, an informational equivalent, an experiential equal of the photo-object. It is most assuredly not. The elephant in the room—digitization—barely raised its problematical head. While there is no question that copying of analog photographs provides safe and easy access to fragile originals by means of digital surrogates, item-level digital access can all too easily remove differences in presentational form and perpetuate the notion that photographs can be transposed from format to format without losing the full meaning of the content. Witness this statement accompanying the corporate video How We Serve Canadians: For the Record on Library and Archives Canada’s website:

The future is digital. Converting as many of our assets as possible into digital form means they have the best chance of standing the ultimate test… the test of time. When you convert documents, films, paintings, photographs, music into digital form, they are no longer the prisoner of their original format.9

However, such “imprisonment” is at the heart of the archival mission to preserve the meaning of the document within the documentary universe in which it circulated and generated meaning. It is, therefore, dangerous for resource allocators, archival policy-makers, and collections managers to accept digitization as the cure-all for storage and access ills; equally, it is foolhardy for scholars to accept digital surrogates at face value.

If institutions are going to devote extensive resources to digital content initiatives, then it is imperative that those carrying out the work understand what and how photographs communicate and what makes them meaningful. If quality metadata is the key to successful mass-digitization projects, what, then, are the elements of visual meaning-making in the analog world that must be preserved in the digital surrogate; in turn, we might ask “What are the elements of visual meaning-making in the born-digital world?” The shift of visual content from material object to electronic file carries lessons both ways across the technological divide. Greater awareness of this shift and its lessons about the mutability of photographic meaning opens a path to a greater understanding of images—analog, digitized, and born-digital.

As the digital revolution overtook the course of human communication in the last decades of the twentieth century, anxiety over the inherently vulnerable and potentially ephemeral nature of digital archives and born-digital images produced heightened scholarly interest in the nature and locus of memory, although, remarkably, little attention has been paid to photographs as devices of memory in the burgeoning literature. The Florence Declaration10—drawn up right here at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz in 2009—codified important ideas about archives which extend far beyond their intersection with photographs in “photographic archives.” Its recommendations for the preservation of analog photo archives are based on two convictions: 1) photographic and digital technologies not only condition the methods of transmission, conservation, and enjoyment of photographs, but also shape their content; and 2) analog photographs are not simply visual images but also physical objects, the meanings of which are contingent upon their material form and their existence in time and space. Now, almost ten years later, we understand from some of the papers delivered here that born-digital photographs themselves merit consideration as material objects as well.

Looking forward, how will the function of photographs and archives in society change, and how will the nature and use of photographs and archives reflect that change? Especially unsettling is the “Cloud” as a metaphor for a site of permanent photographic and archival storage. Clouds are impermanent, ephemeral, transitory, ever-changing. There are no adjectives to describe clouds that instil confidence that the Cloud is capable of keeping archives and photographs authentic, trustworthy, and forever safe from a technological Armageddon.

A final concern hovering over the future of our work is the notion of “post-truth” popularized in the wake of the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States. In 1992, shortly after the advent of the first personal still video cameras ushered in digital imaging, William J. Mitchell invited us to grapple with the issue of “visual truth in the post-photographic era” (Mitchell 1992). What, then, are we to make of visual images (analog or digital) in the post-truth era? Is this a reiteration of the crisis of representation that unseated bedrock reality in the humanities and social sciences in the mid to late 1980s (Clifford and Marcus 1986; Marcus and Fischer 1986)? Or is this even more sinister, far-reaching, and unsettling in its ramifications for studies of photography and the writing of its histories?

The conference on Photo-Objects complemented the symposium series dedicated to “Photo Archives” which gave rise to the Florence Declaration. Launched in 2009, the open-ended series has been based on the premise that photo archives are “open, dynamic, and complex structures” which are the result of “sedimentation processes” that produce and transform knowledge. Together, these gatherings have nurtured the reciprocity and interaction between photographic records and academic disciplines, stretched theorizing about photographs and archives, and explored photographic archives, images, and objects in terms of key concepts— memory, objectivity, place—capable of generating fresh ideas and debates. The focus of this conference on “the materiality of photographs and photo archives in the Humanities and Sciences”—has taken as its remit “photographs as (research) objects in Archaeology, Ethnology and Art History.” In fact, as we have witnessed, its agenda has far broader reach and effect than these disciplinary parameters would suggest.

18.1 List of figures

• Fig. 1: Humphrey Lloyd Hime, The Prairie, on the Banks of Red River, looking south, September–October 1858, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1936-273, copy negative # C-018694.

• Fig. 2: [William England] London Stereoscopic Company, The Suspension Bridge, Niagara, 1859, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1988-286, copy negative # PA-165997.

• Fig. 3: Struan Campbell-Smith (Toronto), Red Shoe, 1977, Library and Archives Canada, Accession 1980-193, copy negative # PA-181604, courtesy: Struanfoto, Toronto.

18.2 References

Blodget, Lorin (1857). Climatology of the United States. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Clifford, James and George E. Marcus, eds. (1986). Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hunter, Aislinn (2004). The Interval. In: The Possible Past. Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 96–98.

Marcus, George E. and Michael M.J. Fischer (1986). Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Mitchell, William J. T. (1992). The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

National Archives of Canada (1992). Treasures of the National Archives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Nye, David E. (1994). The American Technological Sublime. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schlereth, Thomas J. (1980). Mirrors of the Past: Historical Photography and American History. In: Artifacts and the American Past. Nashville: AASLH.

Schwartz, Joan M. (2003). More Than ‘Competent Description of an Intractably Empty Landscape’: A Strategy for Critical Engagement with Historical Photographs. Historical Geography 31:105–130.

– (2011). The Archival Garden: Photographic Plantings, Interpretive Choices, and Alternative Narratives. In: Controlling the Past: Documenting Society and Institutions. Ed. by Terry Cook. Chicago, IL: Society of American Archivists, 69–110.

Footnotes

I extend sincere thanks to Costanza Caraffa, Ute Dercks, Almut Goldhahn, and Julia Bärnighausen, as well as the entire “Photo-Objects” research group and the very helpful staff of the KHI who made this research endeavor possible and ensured that everything unfolded seamlessly and on time.

“Asking Uncomfortable Questions” was the title of the workshop, held February 16, 2017 in conjunction with the conference “Photo-Objects. On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences.”

Not included in this volume.

The Prairie, on the Banks of Red River, looking south and its companion The Prairie, looking west, were part of a series of at least three dozen photographs taken by Humphrey Lloyd Hime on the Canadian government’s Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition sent to the western interior of British North America to assess the area’s potential for settlement and agriculture. They were disseminated in conjunction with the government’s Reports of Progress, published in Toronto in 1859, and the popular Narrative of the Canadian Red River Exploring Expedition of 1857, and of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan Exploring Expedition of 1858, which appeared the following year in London, both written by the expedition leader, Henry Youle Hind.

Blodget’s initial report was printed “by authority of the [United States] War Department” and distributed early in 1856 (viii).

In 1859, William England, chief photographer of the London Stereoscopic Company, was dispatched to North America to produce the company’s first series of New World views. He toured the United States and Canada at a time when the monumental Victoria Bridge was under construction in Montreal for the Grand Trunk Railway and the clouds of war were gathering over the slavery question south of the border. This is one of the few photographs England produced in both stereo and large format.

For a fuller contextualization of H. L. Hime’s The Prairie, on the Banks of Red River, looking south, see Schwartz 2003, 105–130. For a detailed examination of William England’s photograph of Niagara Suspension Bridge, see Schwartz 2011, 69–110.

This photograph was created by Toronto fashion and advertising photographer Struan Campbell-Smith for an advertising campaign by the Quinto Shoe Company. Never used as intended, it was one of twenty-five prints acquired from the photographer the Aperçu series by the then Public Archives of Canada (accession 1980-193) and exhibited from June to October 1980. It appeared in two trade publications and was reproduced in Treasures of the National Archives of Canada (1992, 354) with the following text (unattributed, but written by Lilly Koltun): “The juxtaposition of a female torso dramatically hovering over a high-fashion shoe epitomizes the increasing propensity to sexualize material consumption in contemporary Canadian advertising. More than a document of a particular fashion trend in footwear, the ostensible subject of the image, this photograph transmits cultural values and mores codified into the language of ‘sell.’ Beyond any representation of the product, the image seeks to seduce the viewer by its symbolism: sophistication, youth, sexuality, power.”

Library and Archives Canada. Video and transcript: How We Serve Canadians: For the Record. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/news/videos/Pages/for-record.aspx?=undefined&wbdisable=true#wb-sec, accessed December 18, 2017.

https://www.khi.fi.it/FlorenceDeclaration, accessed December 20, 2017.