Photographs are constantly on the move,1 accumulating traces of use and layers of meaning. They have “social biographies”2 in the sense that they pass from one hand to another, travel through various institutions, and circulate in different political, social, and cultural contexts. In the archives, their journey continues from one section to the next, from one box to another. It is these layers of sedimented knowledge that increasingly attract the attention of scholars.3 In addition to the image itself, researchers have come to see and reflect on the material qualities of photographs such as the mounting, cutting, retouching, and coloring, and on various forms of inscriptions on the recto and verso. Not only do photographs depict objects, they are also “three-dimensional” objects themselves (Edwards and Hart 2004, 1). This is what can be described as the double “objectness” (doppelte Objekthaftigkeit) of photographs.4

In the present paper, we would like to take this idea one step further and think about photographs not only as two-sided objects but as “multiple originals” (Schwartz 1995, 46) leading “multiple lives.” Like Edwards and others, we refer to the “lives” of photographs in a material sense: Notes, stamps, and other traces of use generate material biographies of the photographic objects that are always linked to the social, political, and cultural contexts of their time. In every journey, there are winding roads, crossroads, and dead ends: various paths that are all intertwined. How we choose to view photographs, whatever interests us at a certain point in time, will determine how we tell their stories: which paths do we want to follow and why? We would like to reconstruct some of these multiple photographic itineraries,5 meaning their routes traveled or journeys made, the various formats they were presented in, the hands they passed through, the boxes they were stored in.

In our project entitled “Photo-Objects. Photographs as (Research) Objects in Archaeology, Ethnology, and Art History,”6 we discussed photographs as material objects and their substantial uses in these disciplines. From a transdisciplinary perspective, we examined four holdings by the project partners dating from roughly 1850 to 1945 and representing specific disciplinary practices with “documentary”7 photographs: the photographic collection of applied arts at the Photothek of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, the archiving of monuments in the architectural photographs from the US and Europe around 1900 at the Kunstbibliothek’s (Art Library) Photography Collection, archaeological excavations in Asia Minor and their photographic documentation in the Collection of Classical Antiquities, both housed in Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, and ethnographic photographs of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv at the Institute of European Ethnology which is part of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

The “Photo-Objects” project was based on an intensive comparative exchange. Through tandem research8—reciprocally organized collaborative research in the four archives—we compared the materialities of photographs and their historical uses as well as reflected upon our own concepts, methodologies, and handling of photo-objects. This paper intends to show how a material and comparative perspective may enrich the analysis of photographs. Setting different photo archives and photo-objects in contrast to and in dialogue with each other enables us to identify and reflect upon our own disciplinary standpoints and think in new dimensions. It is precisely this approach that teaches us openness and delight in the unknown. We learn to look with fresh eyes at what we thought we already knew.

Writing a text about four photo archives in the spirit of this inspiring comparative partnership is a challenging endeavor. It means transcending the individual very different archival histories while at the same time explaining these adequately. The paper does not represent the archives as a whole. Instead, they are described under thematic aspects exemplifying various facets of photo archival practices. We would like to ask our readers to indulge us as we move to and fro, jump back and forth, and think in loops. This is certainly not intended to force anyone to play an intellectual mind game but it is fundamental to our comparative approach.

In the following, we would like to discuss some of our comparative insights with respect to the formats, formations, and transformations of photographs in our four photo archives, considering the material changes that accompany the processes of archival meaning-making. While in the first chapter we describe the various formats in which photographs were presented and used in our archives, the second chapter will consider them within the framework of their specific cultural, political, and social histories. Both the materiality of photographs and their socio-political contexts determine how we treat and think of them. Archives are part of disciplinary formations, which in turn also affect how knowledge is structured within a given discipline. Finally, we would like to show how none of the archives presented in this paper constitute a stable entity. Instead, they facilitate and are subject to various transformation processes and therefore need to be appreciated as dynamic ever-changing “ecosystems” (Edwards 2016).9

Reflecting on the different histories of photographs and photo archives and the way these are told by scholars, including ourselves, contributes to a better understanding of their material, socio-political, and often highly problematic nature. This in turn is an essential approach for critical social analysis, for recognizing, understanding, and reacting to various forms of both visual and material power relations. The social value of photographs and photo archives lies in their appreciation as material, changeable, and political objects. It is these material manifestations, their production and transformations, that are at the heart of the present paper.

2.1 Formats: standardization practices and beyond

“Format” is a common term in photographic and archival practice referring to the standardization of sizes, for example, in books as well as in photographs. Moreover, in the history of knowledge, the term “format” describes specific material ways of shaping knowledge: “A knowledge format is used to produce, mediate, and structure representations of scientific knowledge. The term refers to specific forms of transfer, the spaces in which they occur, and the ways in which they combine to generate a specific type of mediality.” (Davidovic-Walther and Welz 2010, 90–91) Formats of knowledge can range from research notes, photographs, drawings, and graphics to index cards and lists or lectures, publications, collections, and exhibitions—each collecting, selecting, interpreting, and presenting knowledge in different ways (Davidovic-Walther and Welz 2010, 94–95).10 Thus, various “knowledge formats” enable a variety of uses and mobilities, while excluding others.

In our four archives, we are confronted with many different material formats: everything from mounted and unmounted photographs produced by various techniques to contact prints and sheets, index cards with and without photographs, slides, glass negatives, film rolls, and so on. In a broader sense, all of them constitute visual media, but they are also so much more than that: as photo-objects, they facilitate or afford different forms of use. Positive prints suggest, for instance, that they can be mounted on cardboard, touched, looked at, picked up, laid out, cut, glued together, and also framed or hung up on walls. We would like to show how the different formats of photo-objects invite us to handle them in very particular ways. In what follows, we will concentrate on the mounted photograph as the most common form in our photo archives and, therefore, a common reference object.

In systematic image collections like that of the Photothek at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, the Art Library’s Photography Collection, and the Collection of Classical Antiquities, photographs were (and still are) mostly mounted on standardized pieces of cardboard. The prints themselves, which are normally retouched and sometimes colored, depict works of art and architecture that were organized according to a certain art historical or archaeological canon embodying the structure of the relevant discipline. The cardboard mounts bear inventory numbers and shelf marks, sometimes connecting them to other finding aids such as card catalogues or lists, and various stamps as well as handwritten and stamped notes on the front and back of the cardboards.

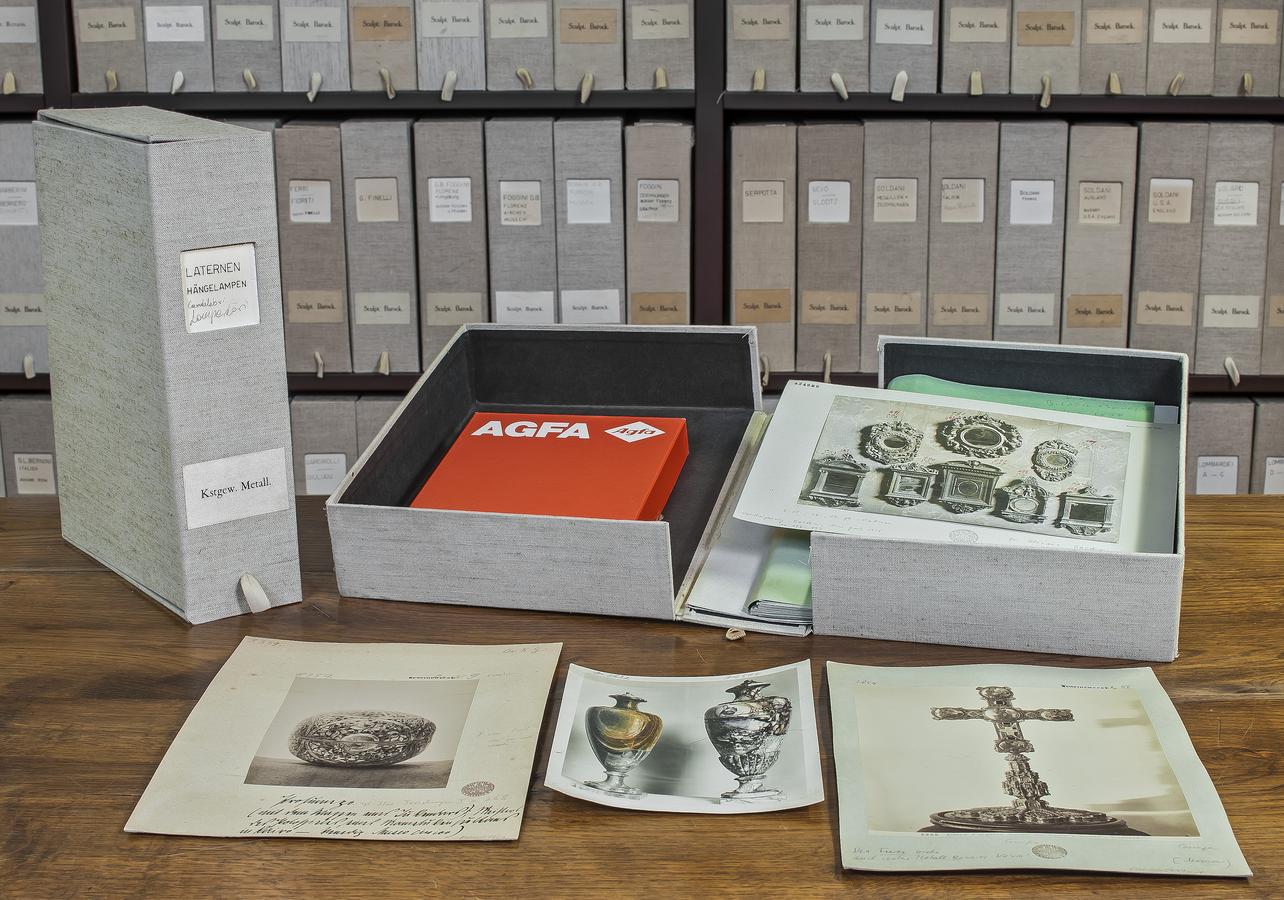

Fig. 1: Cardboards and boxes from the Kunstgewerbe section of the Photothek, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, Photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2015.

Photographs are mounted to be handled. They were (and still are) used as working instruments. Particularly in documentary image collections, users needed to be able to browse through the holdings, lay out images, pass them around, and compare them. The mounting of photographs facilitates “legitimate handling” (Edwards 2014, 4) that protects them physically while ensuring access to their content. Therefore, large tables are very often essential furniture in a photo archive in order to allow the mounted photographs to be distributed and to encourage the practice of comparing photographs. Visitors to the archive can combine, juxtapose, and isolate the images in new ways.11 They still do this to this day, although mainly for other, new research purposes (Klamm 2016).

Fig. 2

The photographs in those archives are mostly stored in boxes standing upright on shelves. This form of presentation, which strongly resembles that of books in a library, functions as an open-stack research tool for employees, scholars, and other users—depending on the archives’ assignments and on the admission policy of their institutions (see Fig. 1, see also Fig. 2 of the Collection of Photography at the Art Library in Hyperimage).

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Sometimes cardboards would be kept in register-like cabinets as is the case in the Collection of Classical Antiquities (see Fig. 3 in Hyperimage) or in folders as previously archived in the Art Library (see Fig. 4 in Hyperimage). All these installments allow faster access to the photo-objects while structuring them in classified grids (shelves) that are named according to art historical or archaeological categories, in this case: topography or applied arts. These are regulations concerning all storage furniture that have to be met by users. Some of these furniture are complex, encouraging certain forms of handling while hindering others (te Heesen and Michels 2007; Klamm and Wodtke 2017).

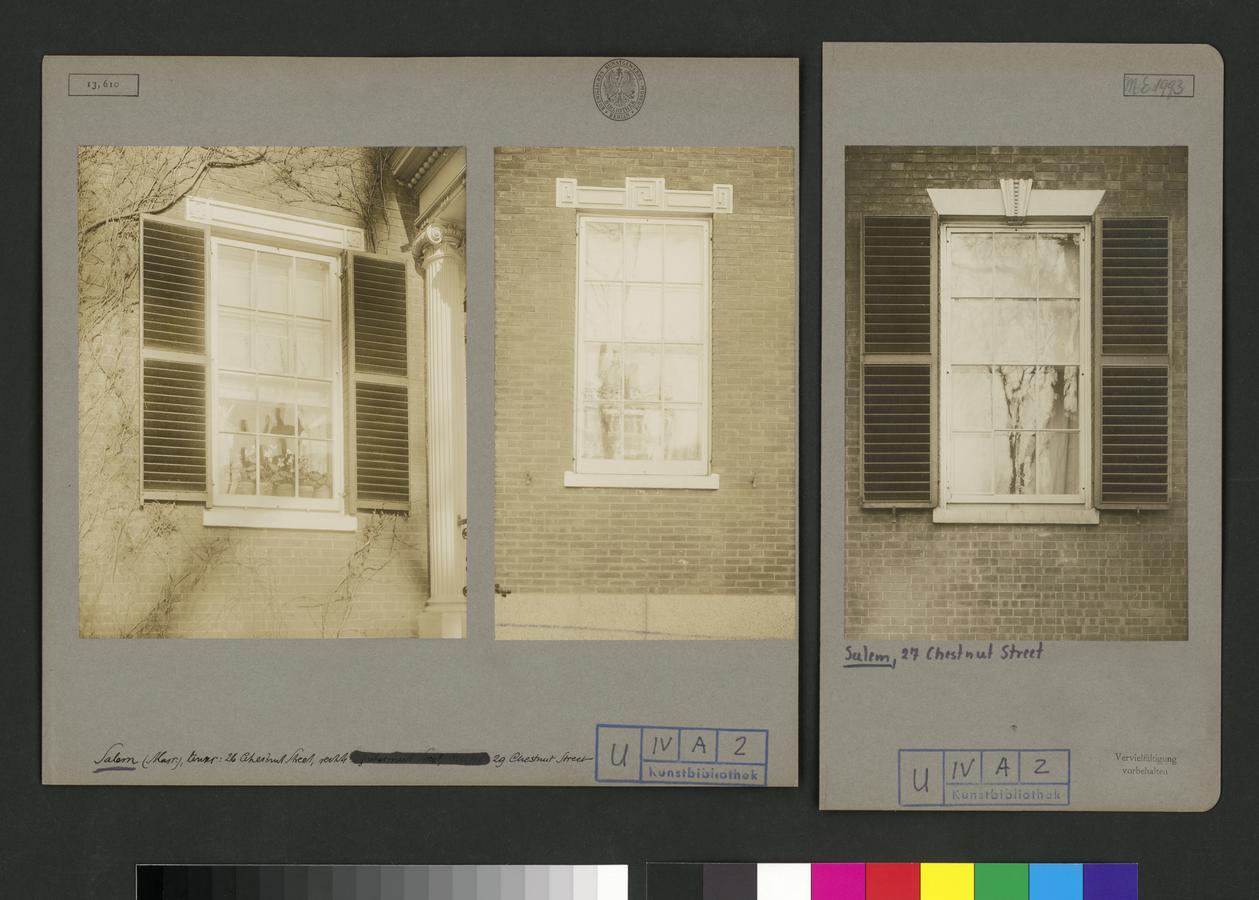

Fig. 6: Salem (MA), windows in Chestnut Street 26, 29, and 27, Frank Cousins, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, c. 1900, left: 20.3 x 16.1cm (photo), center: 20.4 x 12.4cm (photo), right: 20.4 x 14.2cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

The Photothek of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz holds approximately 620,000 photographs of works of art from late antiquity to the modern era with a traditional focus on the Italian Renaissance. In recent years, photographic campaigns as well as activities by individual scholars and research groups have added to the holdings in response to a broadening of the scope of study to the Mediterranean as a cultural hub—always underpinned by postcolonial critique. Mounted photographs form the main holdings of the Photothek and follow a systematic notation scheme starting with an inventory number in the top left-hand corner and a shelf mark in the top right-hand corner (see Fig. 5 in Hyperimage). The official KHI stamp is in the center below the photograph, the title and date of the artwork depicted are on the left, its location and provenance on the right. Sometimes, there will be a book reference on the far left-hand edge of the cardboard referring to the artwork depicted as well as copyright remarks and digitization numbers on the far right relating to the photographic image. The shelf mark refers to the classification of the photographs into four main genres that are well known among art historians: painting, sculpture, architecture, and applied arts. As we shall see later, this system is not (and never has been) stable or objective. It has expanded, branched out, and has many surprises in stock (both problematic and inspiring at the same time).

At the Art Library, photographs were also mounted on standardized cardboards, and depending on the size of the print, they were put together in pairs or even triples, reflecting disciplinary typologies. As a requirement of the archival arrangement (and quite similarly to the KHI) the photographs were all stamped with the signum of the library, uniformly labeled with, for example, an acquisition number, a title, and a classificatory reference number. This is the case with the architectural photographs by American photographer Frank Cousins (1851–1925) (see Fig. 6). In the top left-hand corner of the cardboard, an embossed stamp signifies the entrance and—at the same time—inventory number of the bundle of photographs. On the right-hand side, there is an alphanumeric signature referring to the archive’s classification as well as the embossed signum of the possessing library of the (then) Royal Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin (Königliches Kunstgewerbe-Museum Berlin Bibliothek), today’s Art Library, in the middle.

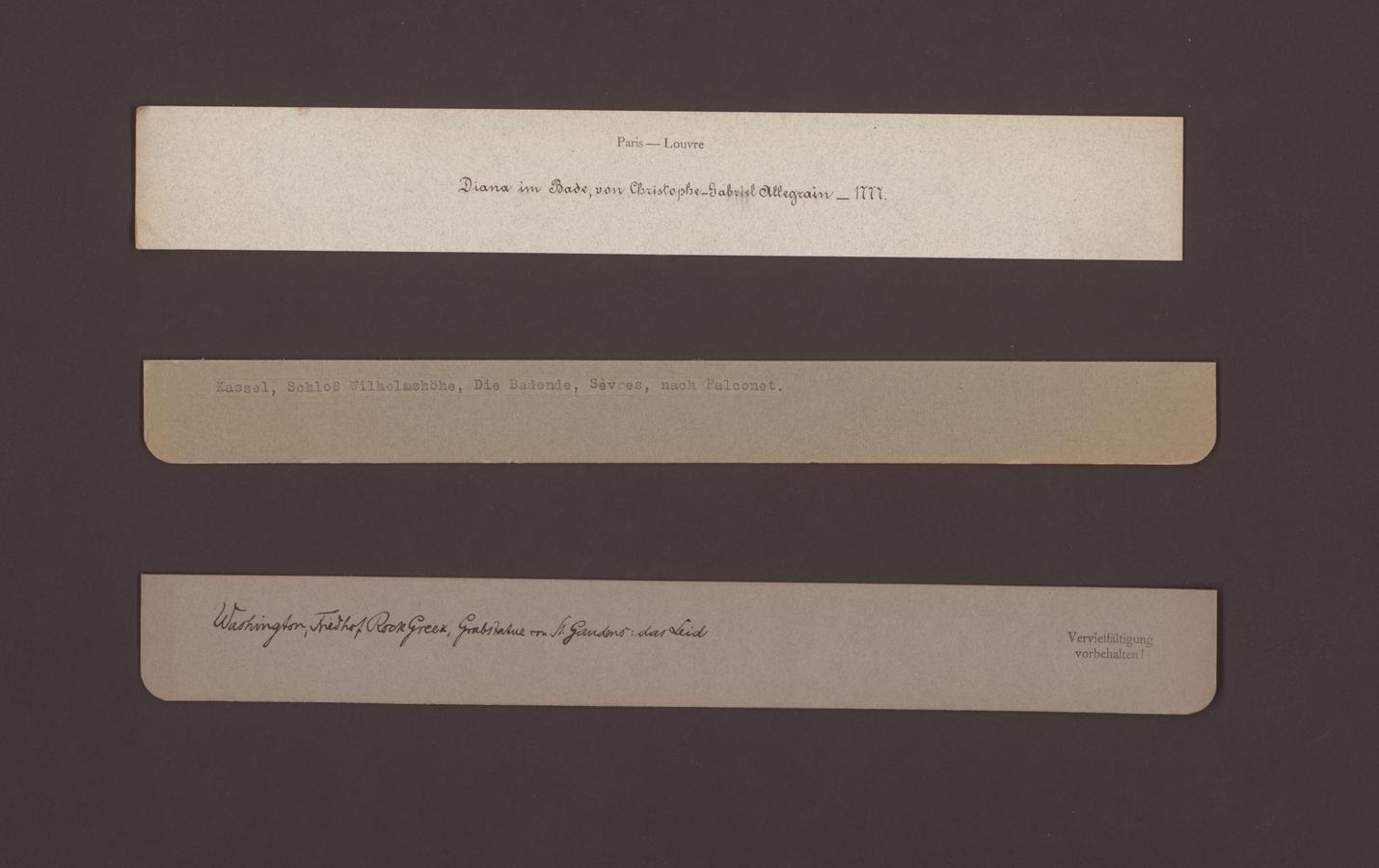

Handwritten notes below the prints describe what can be seen in the photographs: “Salem (Mass.), left: 26 Chestnut Street, right: 27 Chestnut Street, middle: 29 Chestnut Street.”12 In the bottom right-hand corner of the cardboard, a stamp with the words “Reproduction reserved” (Vervielfältigung vorbehalten) registers the copyright of the photographer. Thus unified, these photographs were integrated into the classification system of the archive. Similarly to that at the KHI Photothek, the collection at the Art Library was originally organized according to art historical genres (painting, sculpture, architecture, and the applied arts) and chronologies. In the case of this archive, too, however, classifications change, as will be discussed later.

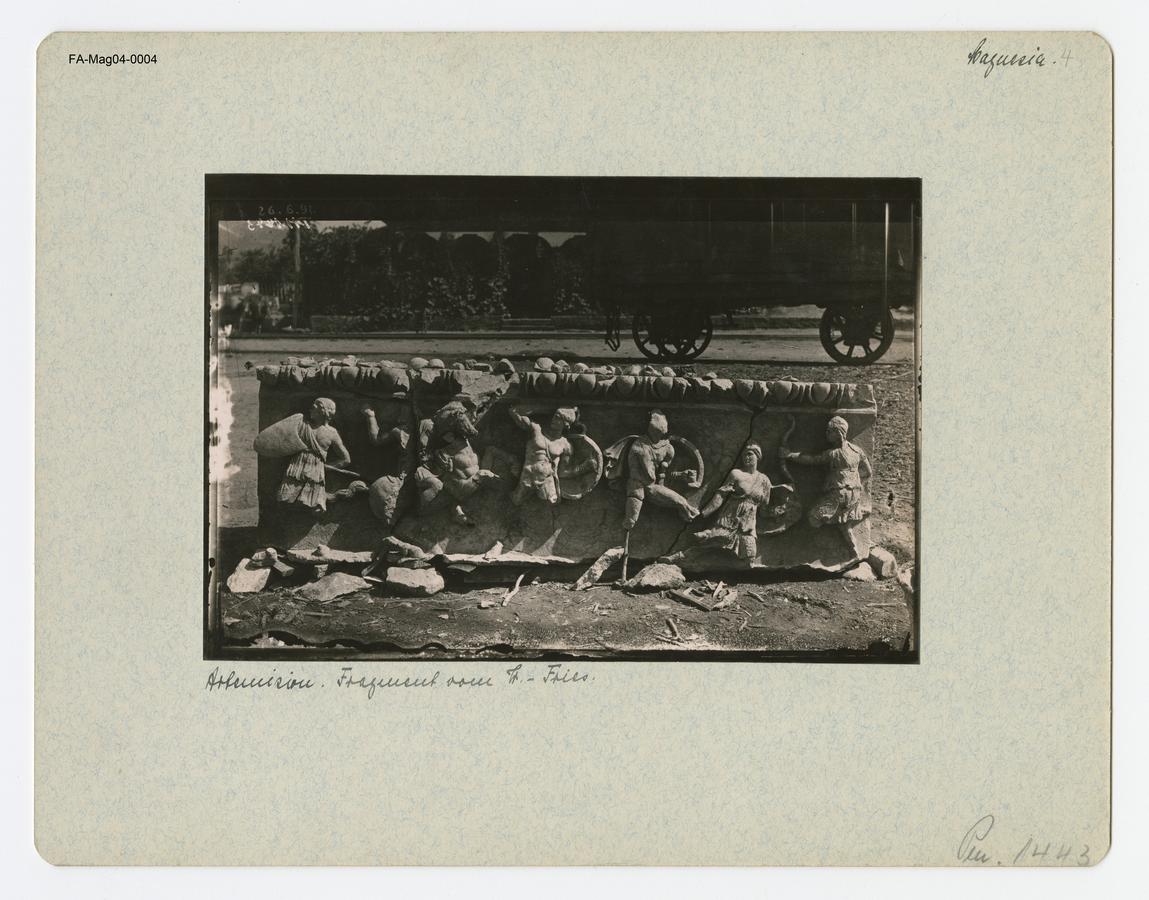

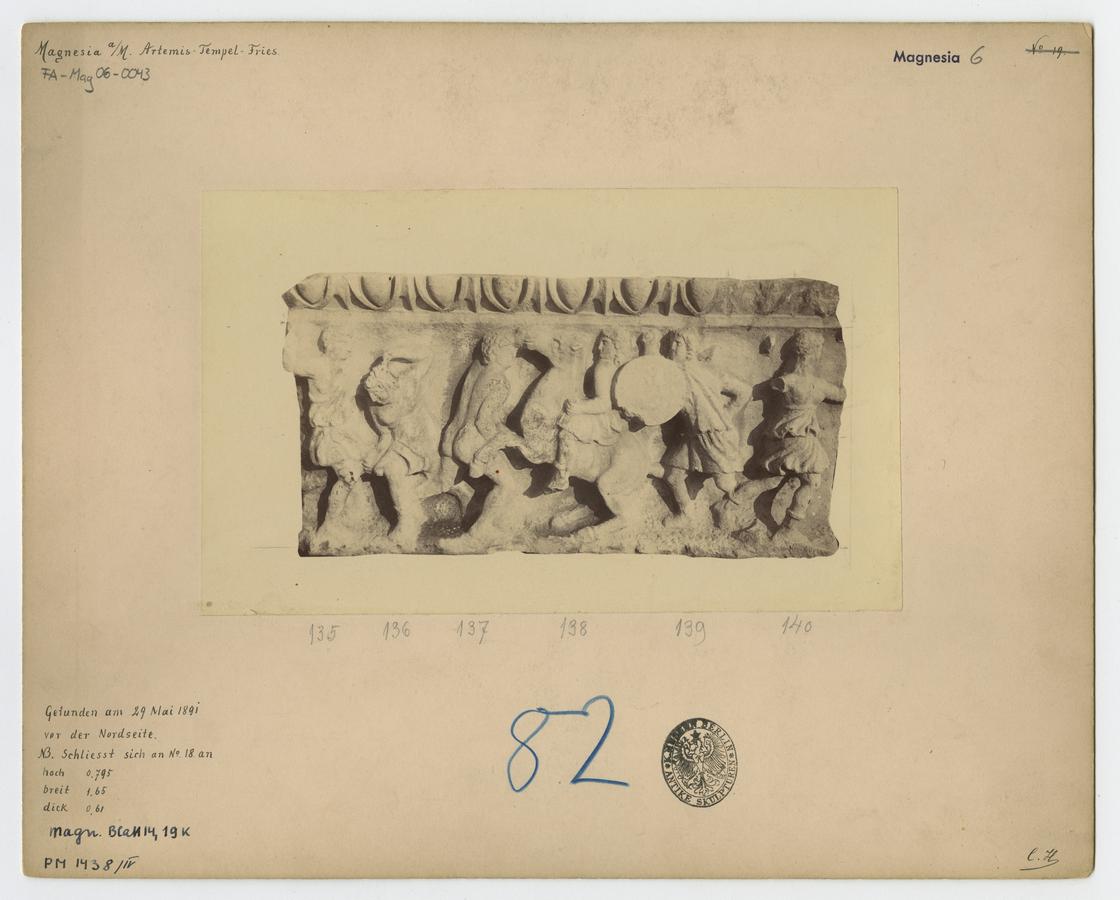

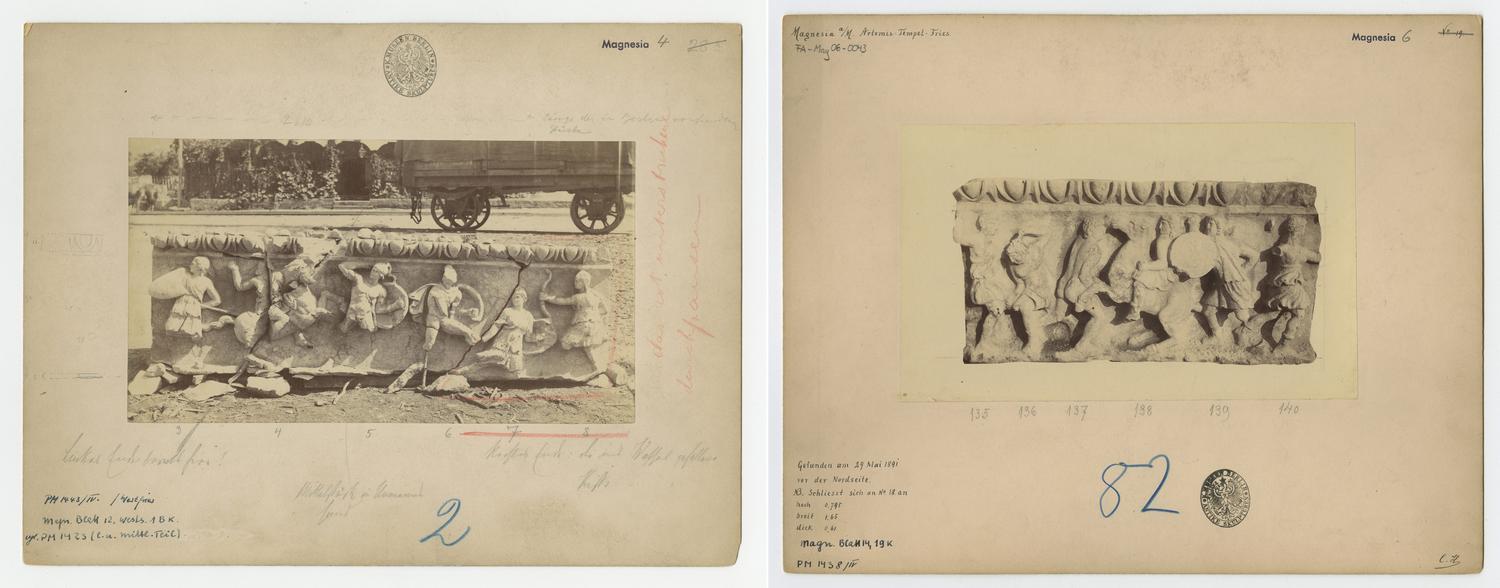

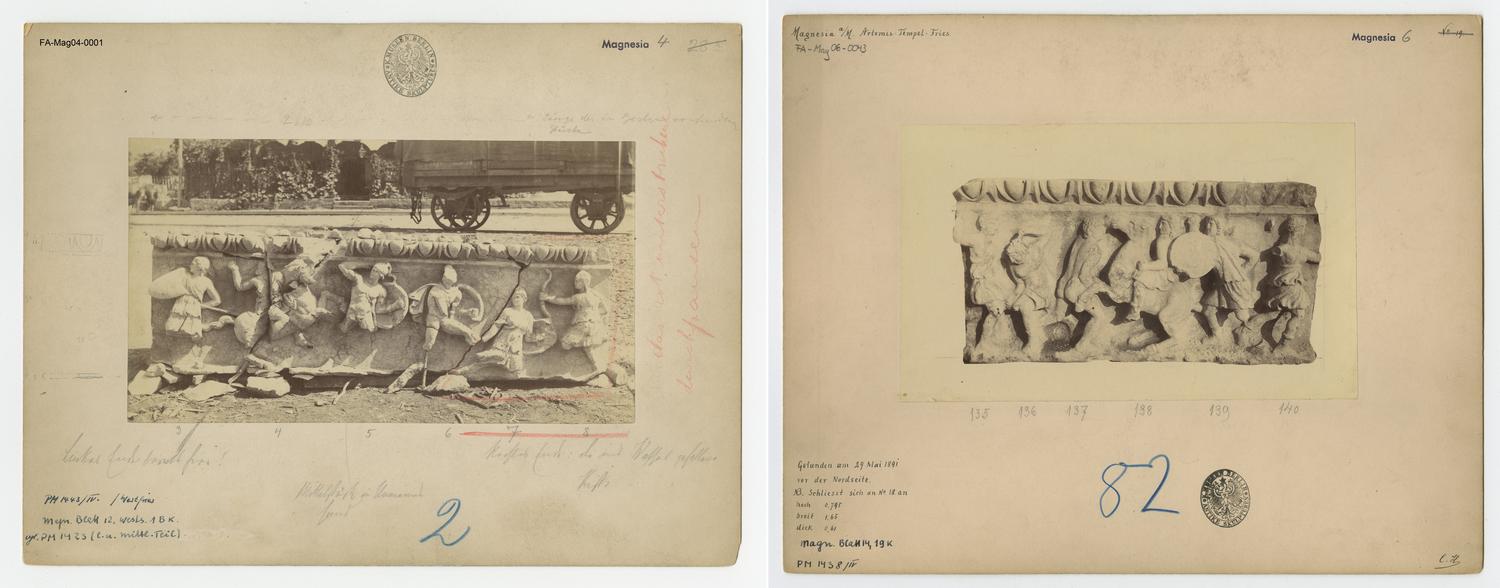

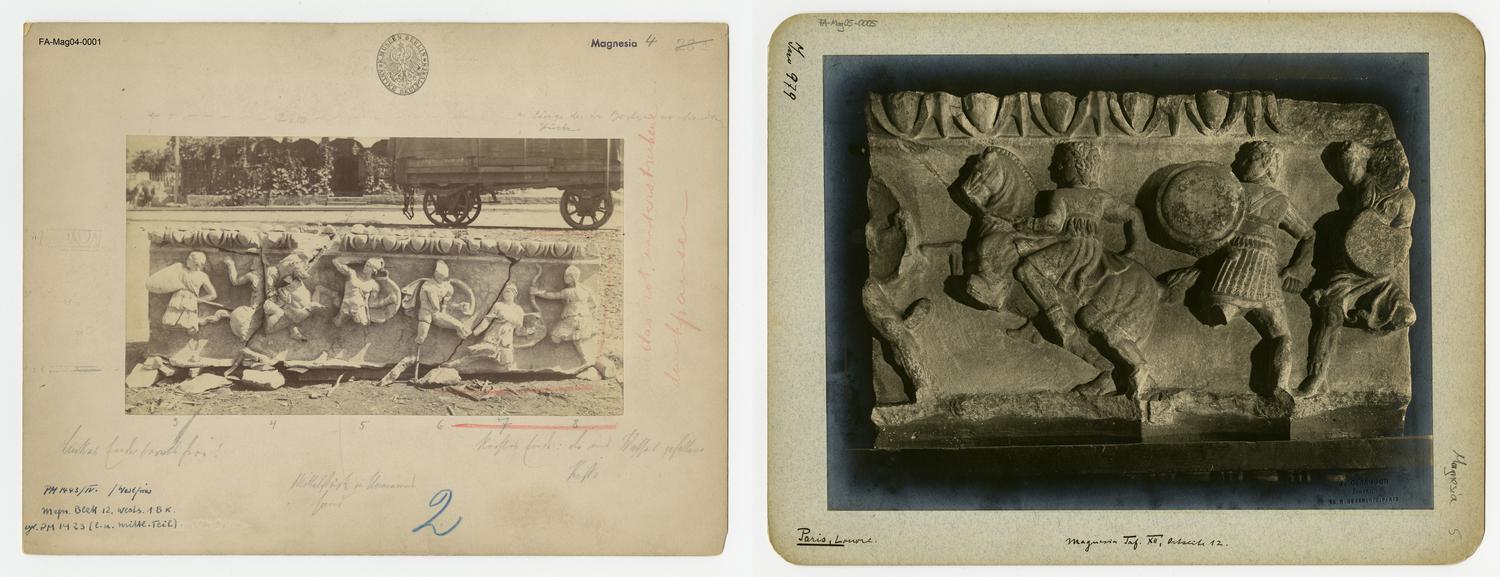

The archive of the Antikensammlung seems to be a hybrid between those at the KHI and the Art Library on the one hand, where archival processes are fully standardized and precisely organized, and the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv with its very different formats on the other hand (see below). The photographs of the Antikensammlung are less homogenous than at the KHI and the Art Library. More than 80,000 are held by the archive, with most of them in the same format: they are mounted on cardboards (Alexandridis and Heilmeyer 2004, 213). However, many of them are also glued in albums, kept in folios, or stored in boxes with other documentation material. Some photographs in the topographical section were taken, mounted, and inscribed during excavations (Figs. 7 and 8).

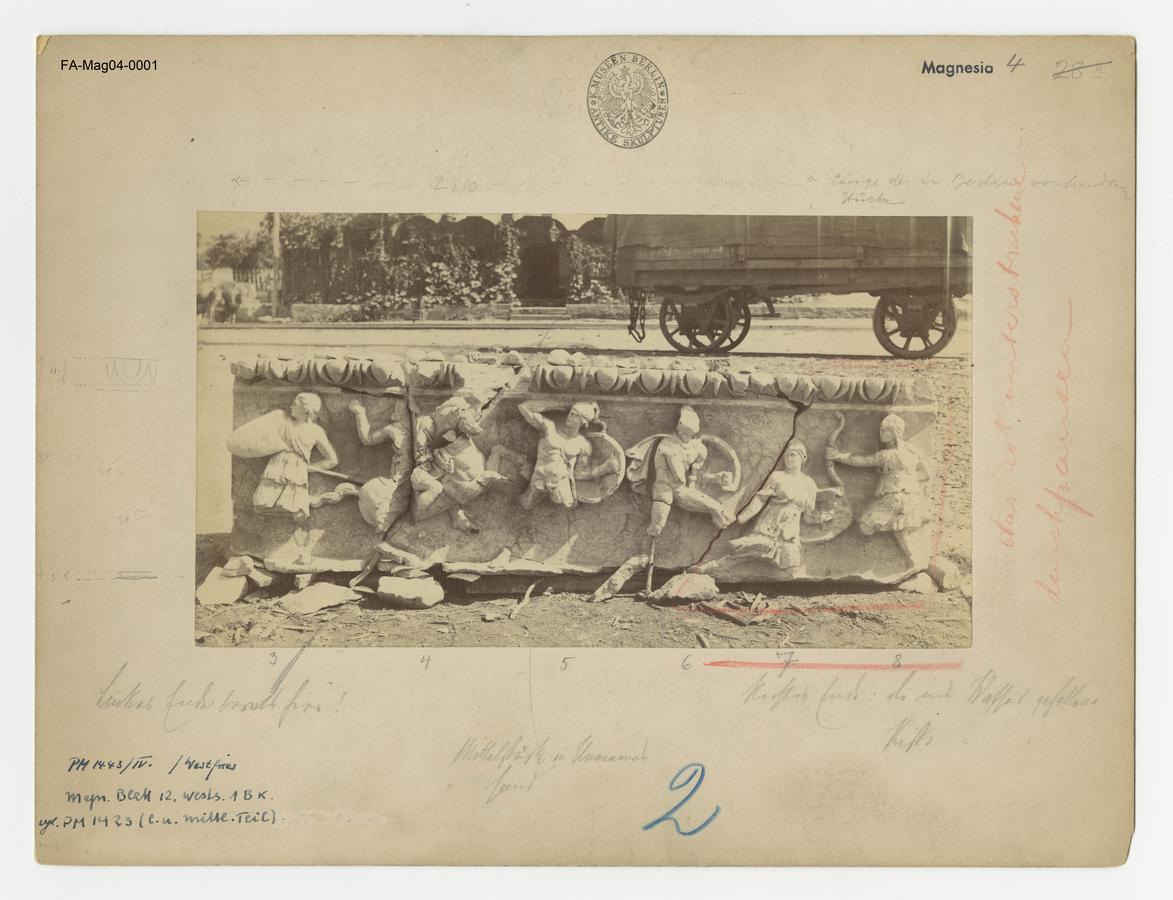

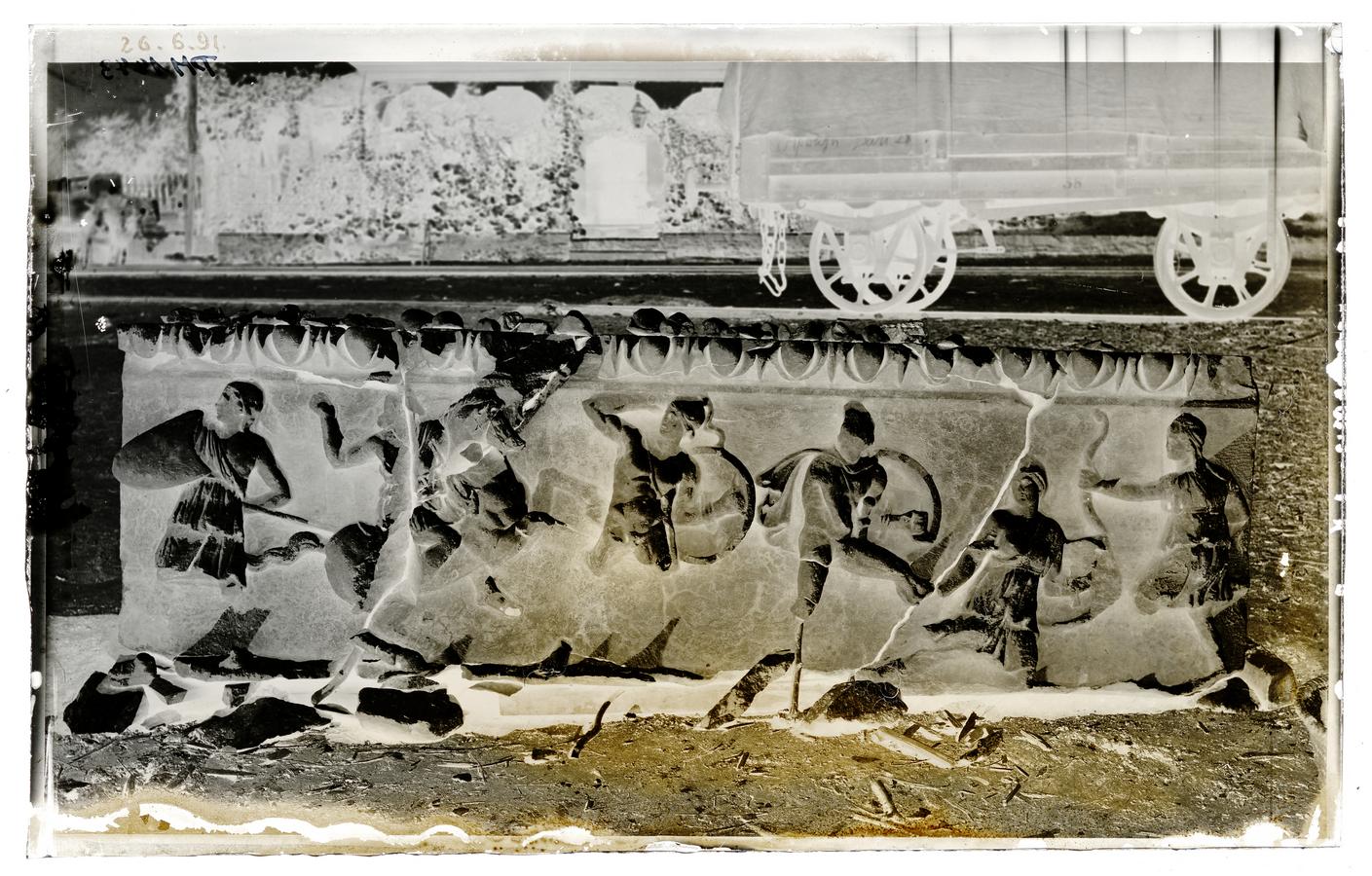

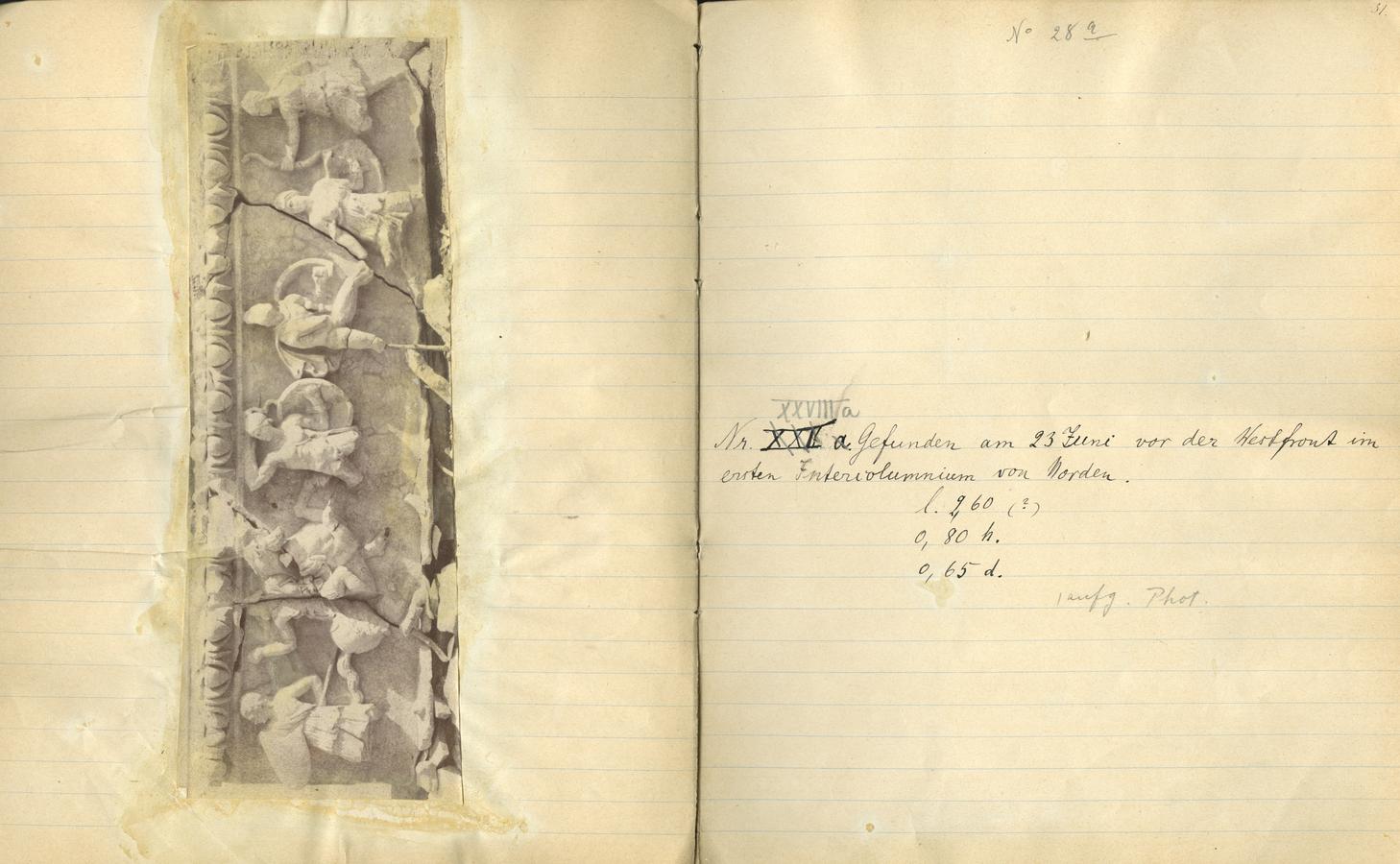

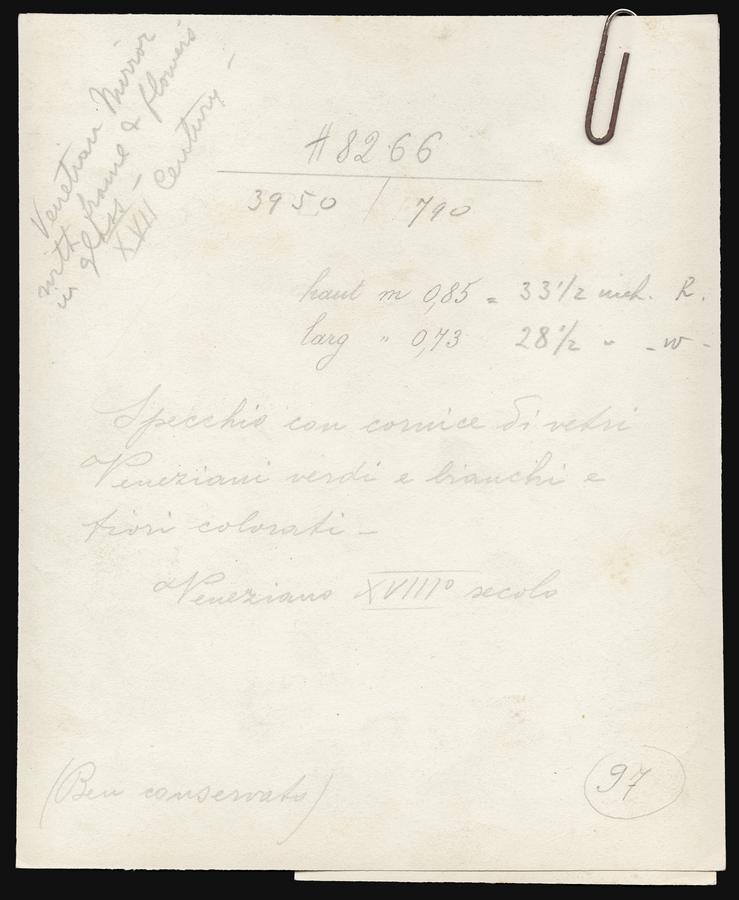

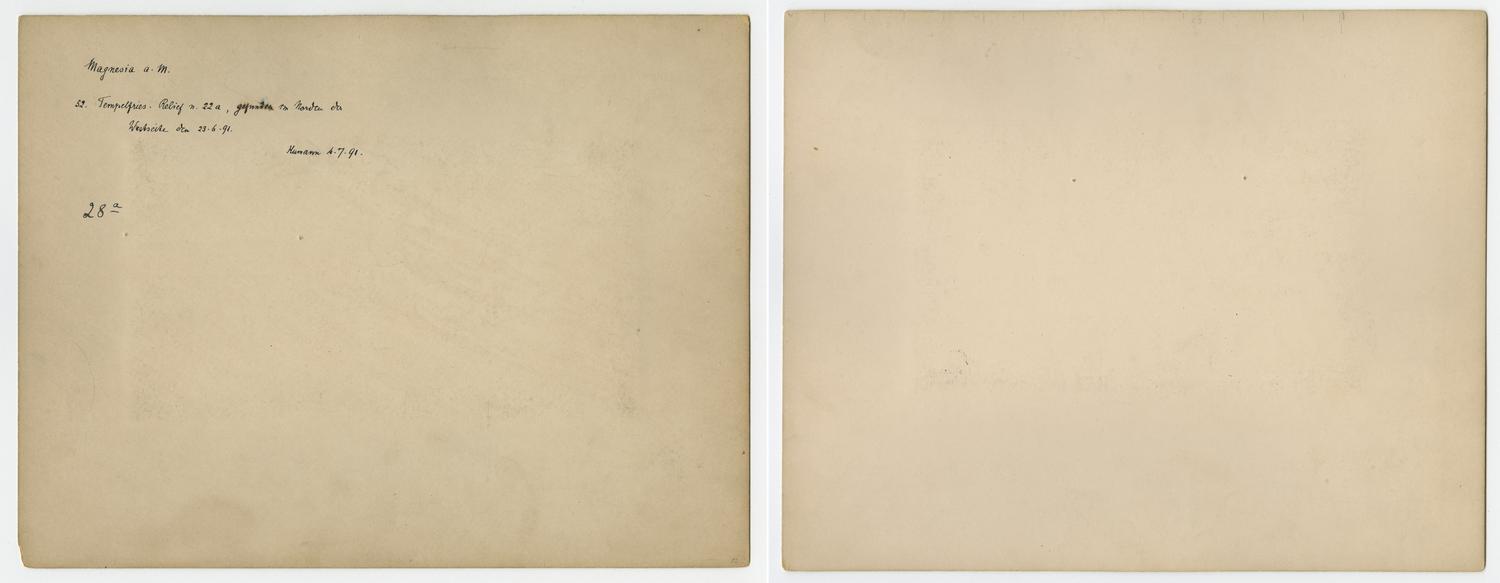

Fig. 7: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 20.2 x 11.3 cm (photo), 21.6 x 28.5 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. FA-Mag04-0001, neg. no. PM 1443.

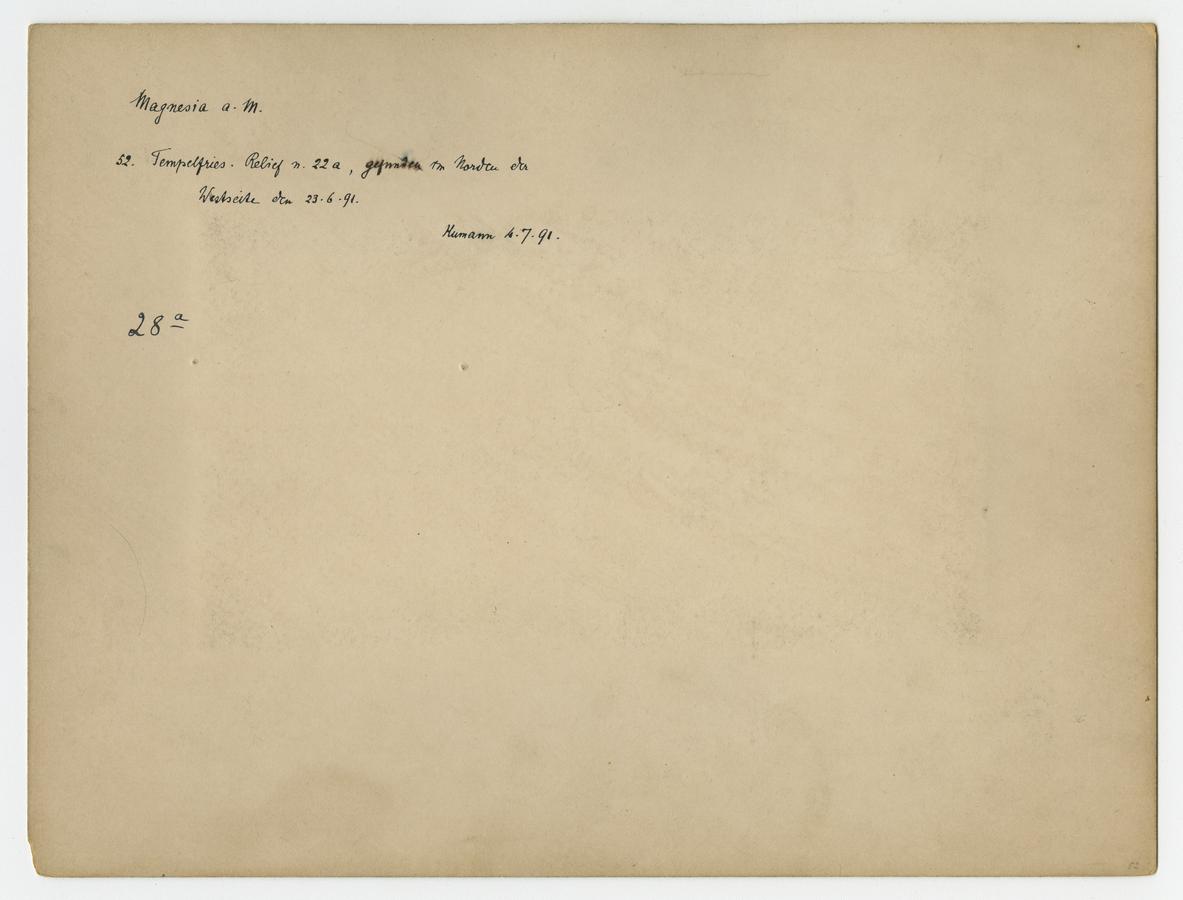

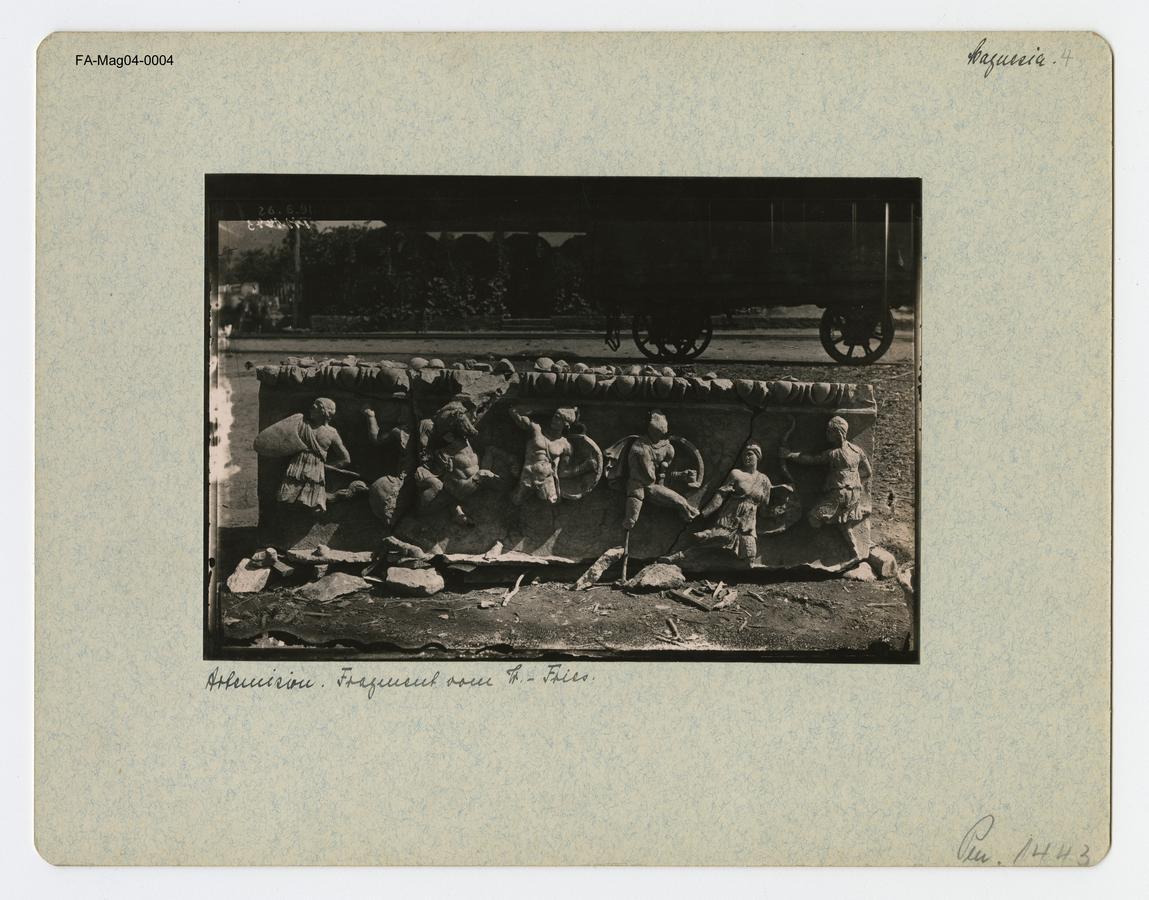

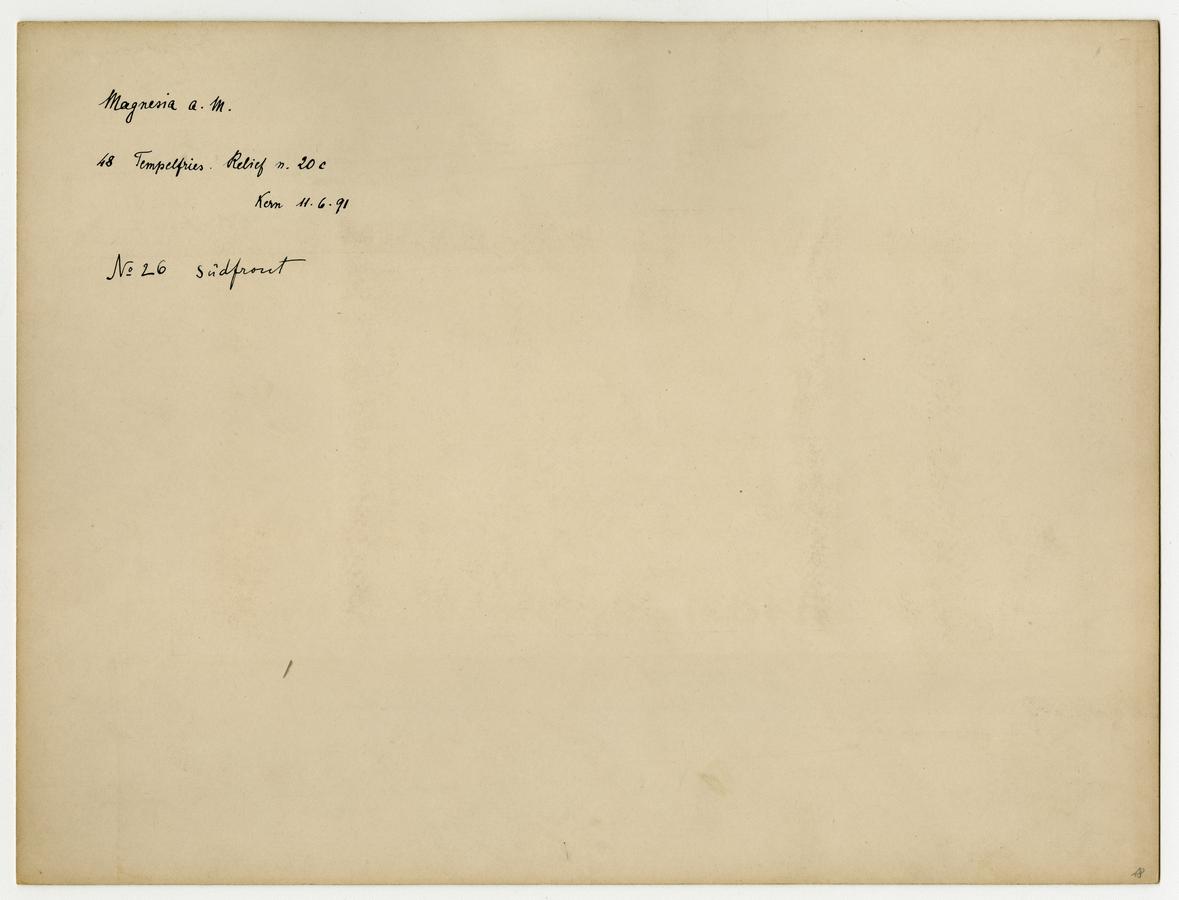

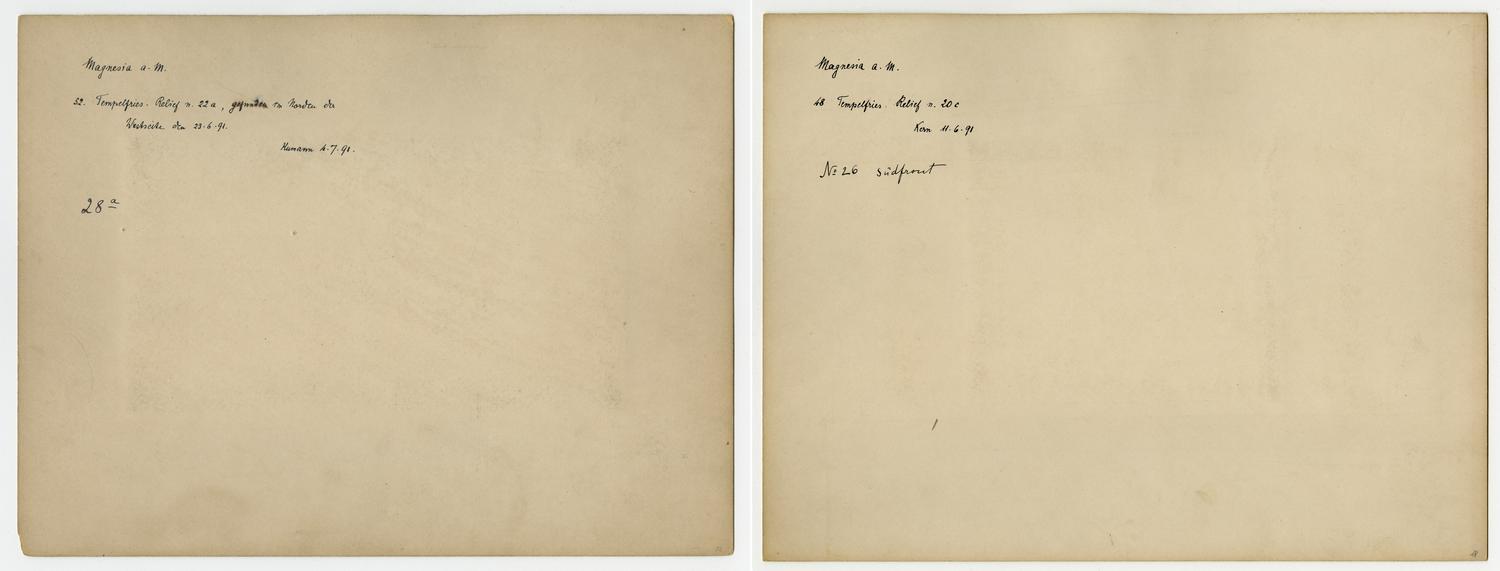

Fig. 8: Verso of Fig. 7: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 21.6 x 28.5 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv.no.FA-Mag04-0001, neg. no. PM 1443.

Fig. 9

Fig. 9a

Fig. 10

Fig. 10a

Every archaeological project of the Antikensammlung developed its own system of archiving photographs: the numbers, formats, and references are different. Even the cardboards vary in size, color, and material. The example of the photographs of Magnesia on the Maeander river is particularly interesting because of the sophisticated and complex notation system and its underlying network structures. At the same time, this kind of complexity and variety is fairly typical of all the excavation pictures. The system in the Magnesia series is based on the individual experience of the director of excavation, Carl Humann, who had formerly worked in Pergamon (Schulte 1963). Every photograph taken, developed, and mounted in Magnesia was marked on the back according to the same standardized inscription system (see again Fig. 8): Apart from the name of the archeological site, there are various numbers suggesting that different counting systems were in use. One or sometimes two figures (e.g., “52.”) are followed by a short description of the object depicted, which is in turn linked to another counting system (e.g., “22a”), and by the date this particular fragment was found. The inscriptions conclude with the name of the editor (“Humann”) and the date of editing. Interestingly, Humann did not write these notes on the cardboard himself. Instead, he left them on the reverse of the photograph. It was his assistant, Otto Kern, who transferred them onto the cardboard after the picture was mounted, thus contributing to the formation of archaeological knowledge (see below).

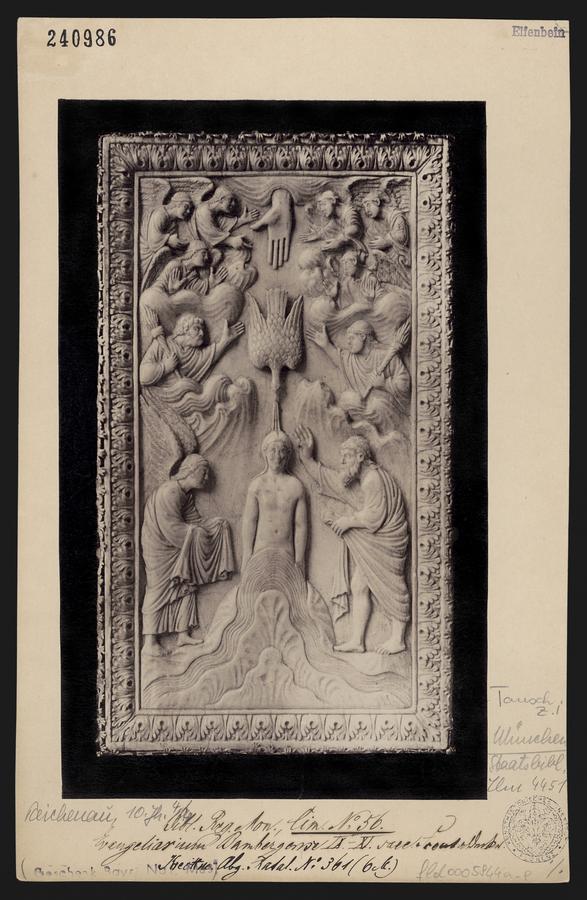

Fig. 11: Ivory relief of Baptism of Christ, unidentified photographer, c.1900, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 27.6 x 17.8cm (cardboard), exchange with the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, inv.no.240986.

Photo archives are, in a way, consistent and structured but never homogeneous or uniform. At the Collection of Classical Antiquities, as we already know, the cardboard mounts very often differ in size, color, and material: probably from the 1910s or at least 1920s onward, there were two sizes of standardized blue mint colored cardboards. In some cases, the pictures mounted on them were printed from an older negative long after the end of the excavation (see Fig. 9 in Hyperimage). Other photographs arrived at the museum with their own cardboards, for instance, when they were bought from photo agencies (see Fig. 10 in Hyperimage), exchanged with other institutions, or given as a present by researchers or colleagues.

Similarly, the photo archives in Florence and at the Art Library hold many prints that have been given to them or acquired from various donors or institutions. Very often their cardboards were simply adopted by the archivists and subject to various types of handling. Archivists at the KHI, for example, sometimes scratched out the old inventory numbers and shelf marks and wrote down their own (see Fig. 11).

Fig. 11a

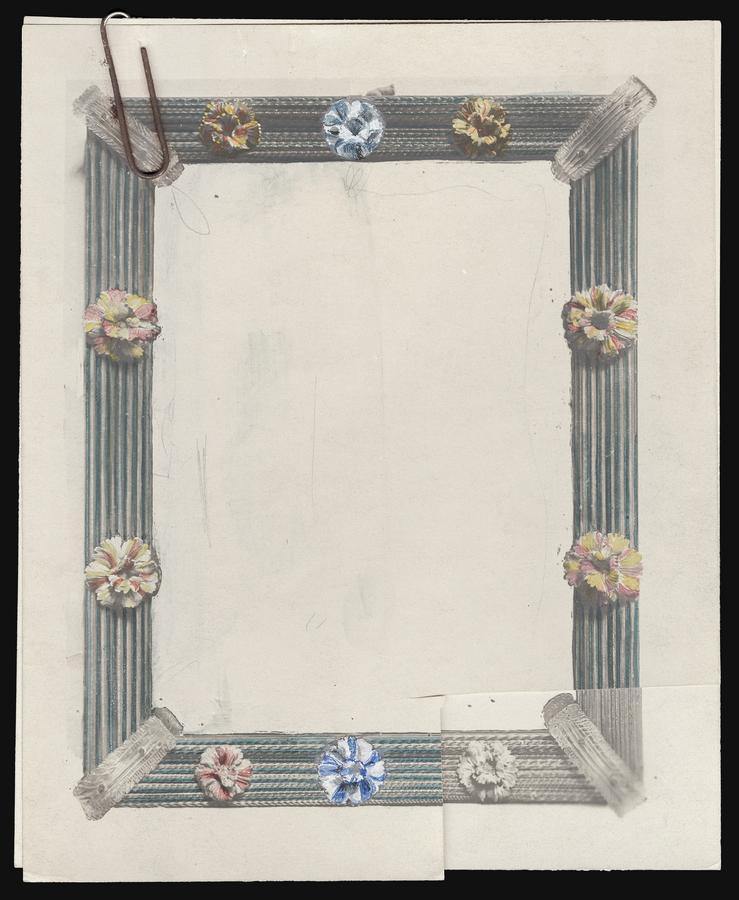

At the KHI, too, we find photographs that have never been mounted at all. These are normally not part of the main holdings, as we shall see in the next chapter. Almost all of the unmounted photographs were inscribed in one way or another before they even entered the Photothek: by hand-coloring the print, by making small drawings, or by making notes about the object depicted on the recto or verso of the print itself. Thus, the material variety of the pre-archival histories of the photographs secretly infiltrates the standardized photo archive. If those photographs were to be mounted, this particular history would disappear. On the other hand, there is never just one history, one narrative, for a photo-object: Photographs do not become stable entities when mounted but keep on transforming: although this was not permitted, visitors to the KHI’s Photothek would sometimes comment on and add to the information provided on the mounts, re-attributing, for example, the objects depicted, thus ignoring archival standards and individualizing the photo-object. However, it is not only the users who transform the photo-objects. As we shall see below, archivists play their part, too, and their role is crucial. Looking at this, how do we cope with the archive’s diversity, with different mounts, modern prints, and added information? The answer is simple. These alleged “shortcomings” of archival standards, of an assumed unity that never existed, in fact constitute a major strength: they lay open processes of decision making, attribution, and (re-)appropriation in the archive, unveiling its history and its politics.

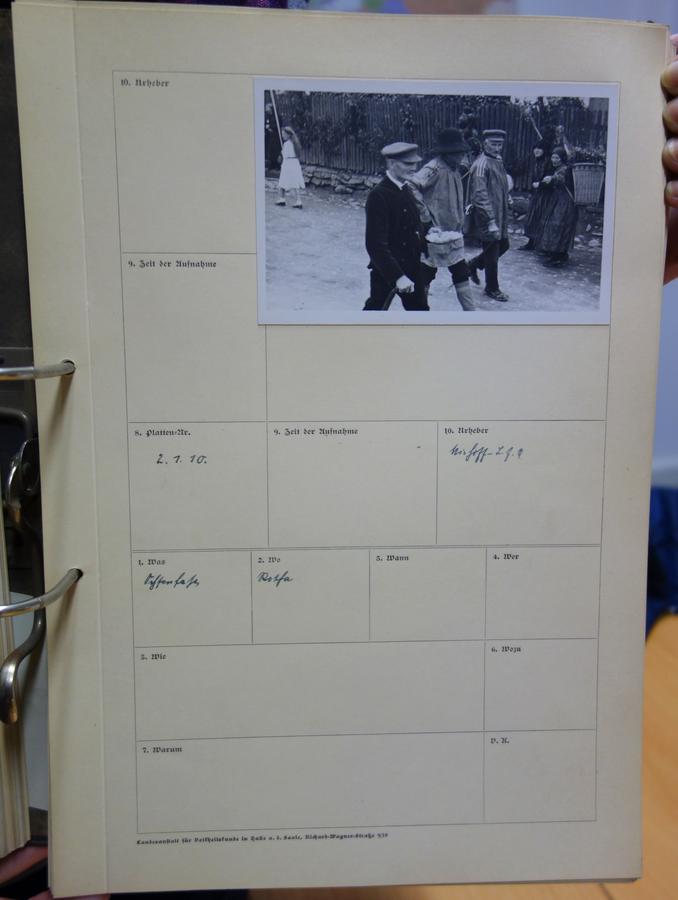

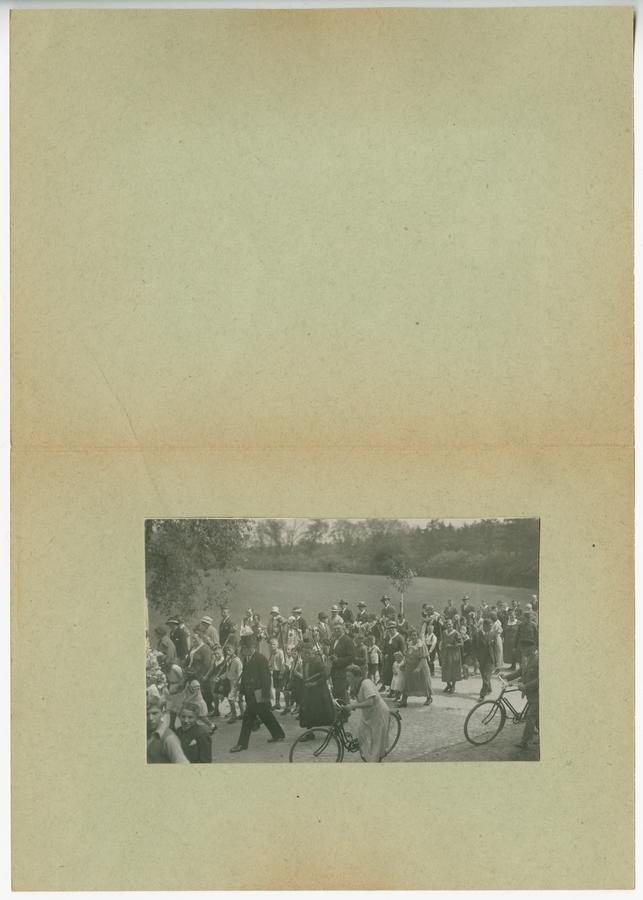

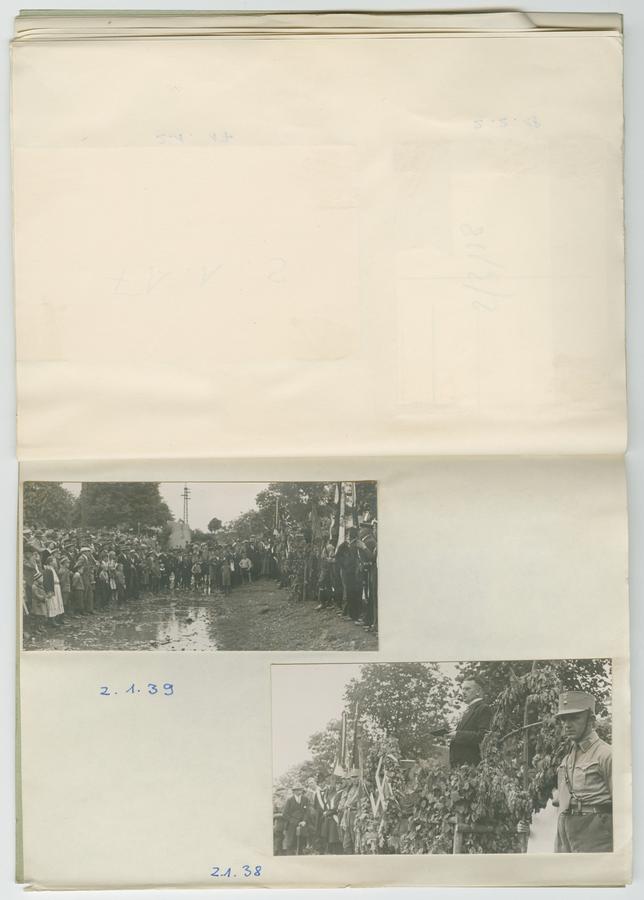

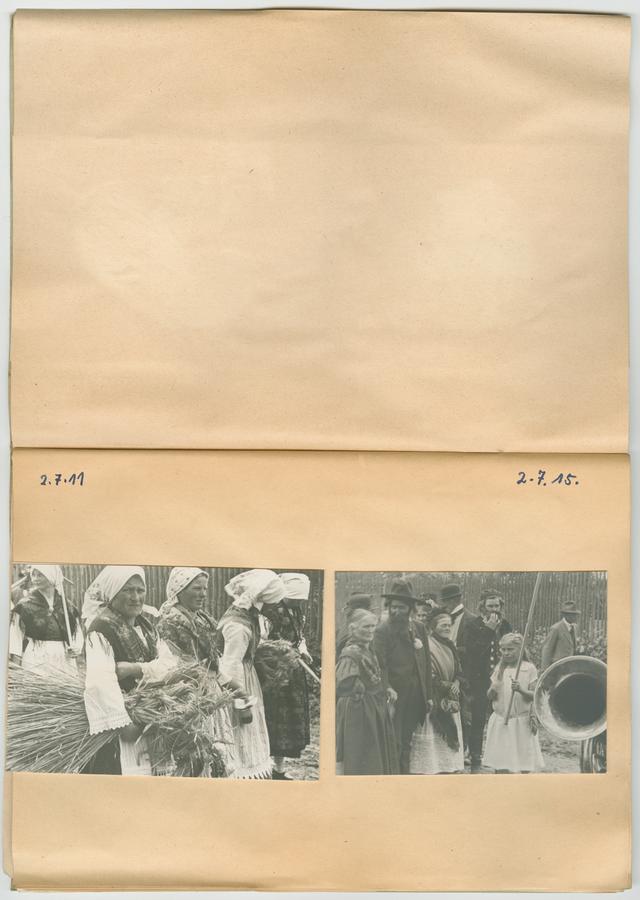

Fig. 12: Record sheet of a photograph from the Ochsenfest in Rotha, in original folder, Heinz Julius Niehoff, photo archive (Hahne collection), Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Fig. 13

Fig. 14

Fig. 15

Fig. 16

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

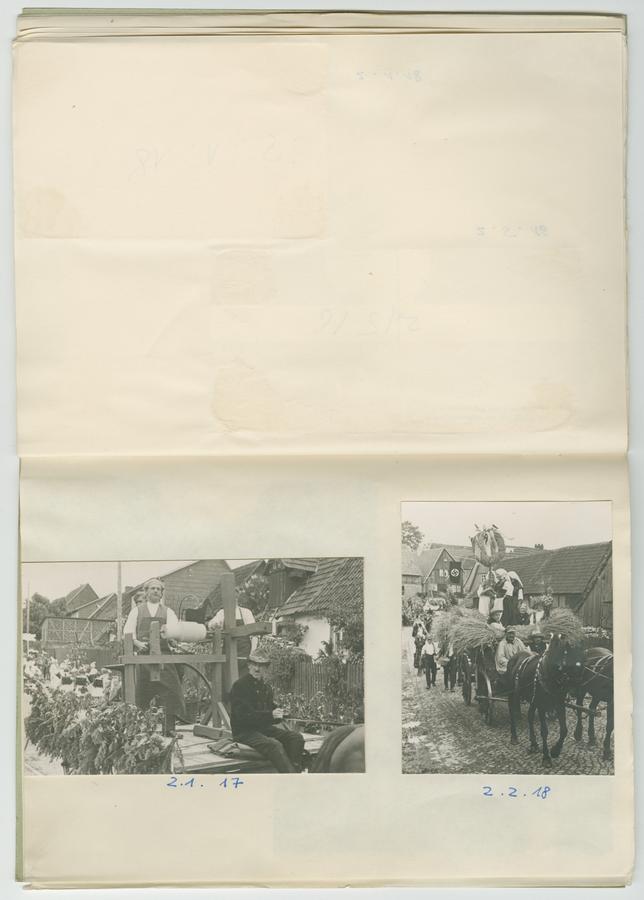

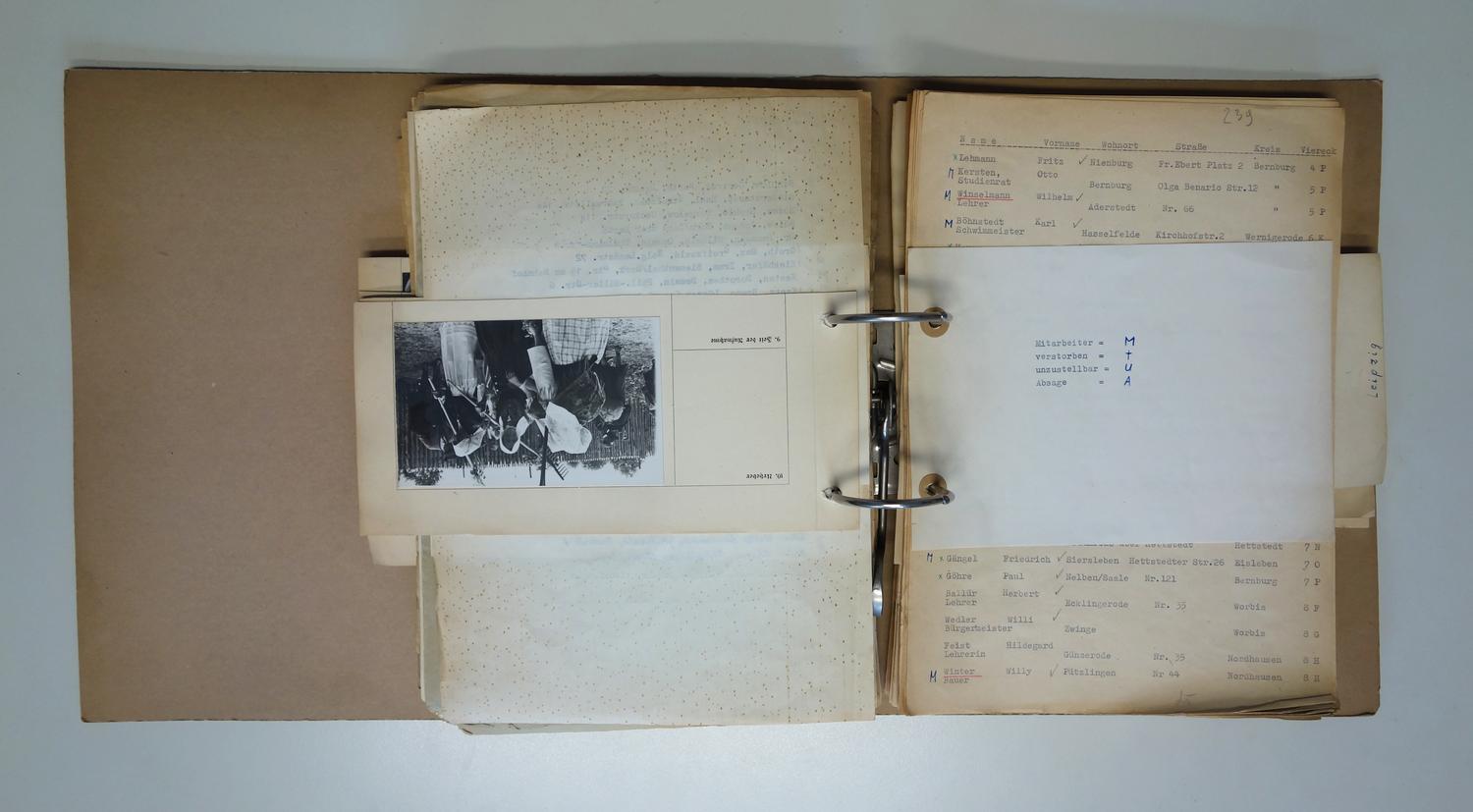

The specific features of the mounted photographs and their storage, use, and handling in the Antikensammlung, the KHI, and the Art Library are particularly evident in comparison to the photo-objects of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv at the Institute of European Ethnology, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, which are fundamentally different in two ways. First, photographs here are glued on record sheets that not only differ from the mounts in the other archives in terms of size and thickness but also because they organize the notations in a tabular form (see Fig. 12). Furthermore, the cardboards are perforated on the sides and filed in thick gray-brownish binders. Similarly to the boxes, the folders were used to put the photographs in a certain order that reflected disciplinary categories. This system operated almost as flexibly as the boxes did. At the same time, it made unintentional changes difficult. The materiality of the folders necessitates scrolling from front to back, as with a book (Krajewski 2002, 163). The weight and size of the folders, however, makes the process of browsing somewhat impractical. The record sheets cannot (and are not supposed to be) laid out on a table as it is the case in the other archives. Bound in folders, they are not expected to function as mobile objects as is the case with the mounted photographs. This exemplifies a second point relating to the above-mentioned practice of “legitimate handling” (Edwards 2014, 4): Mounted photographs on cardboards also enable easy handling of photo-objects during research as well as allowing their mobility in the archive.

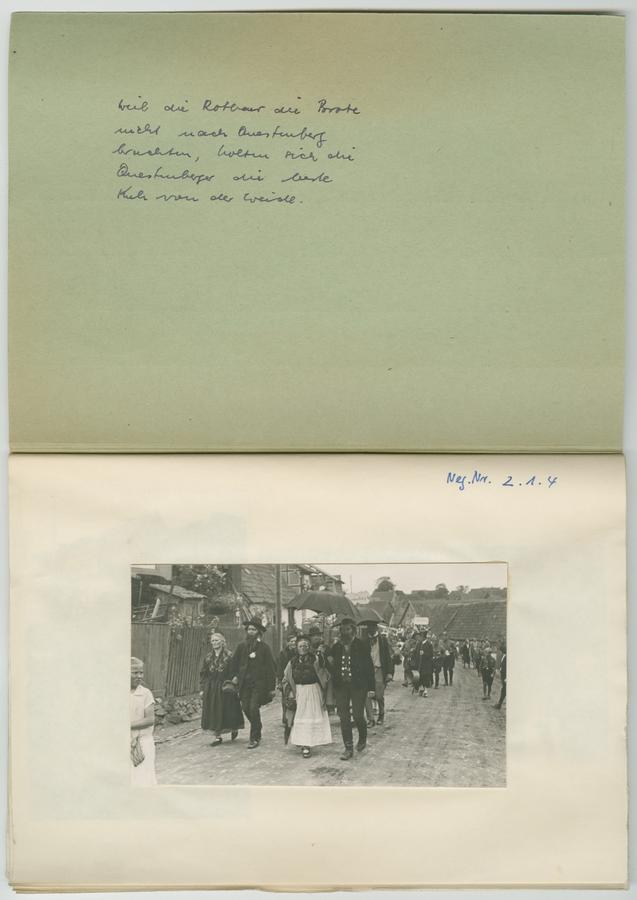

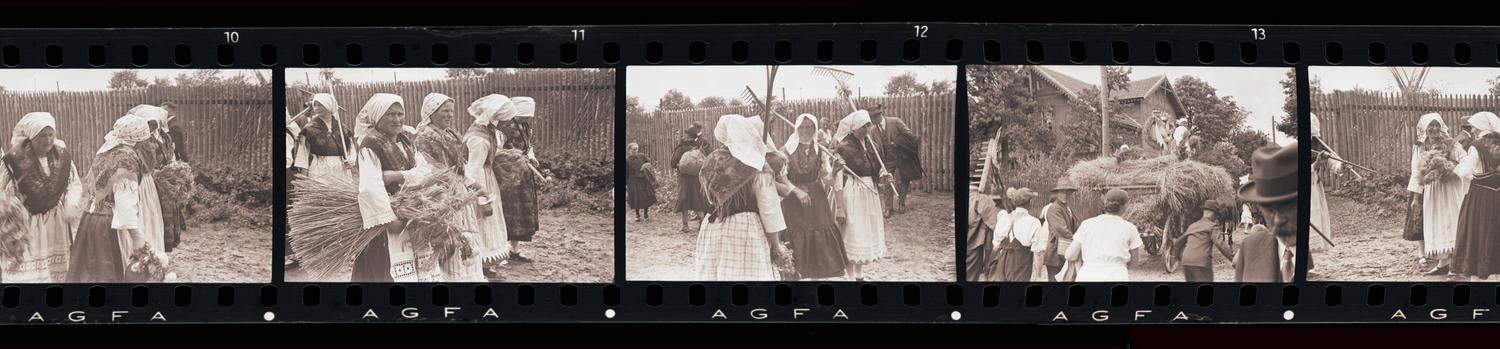

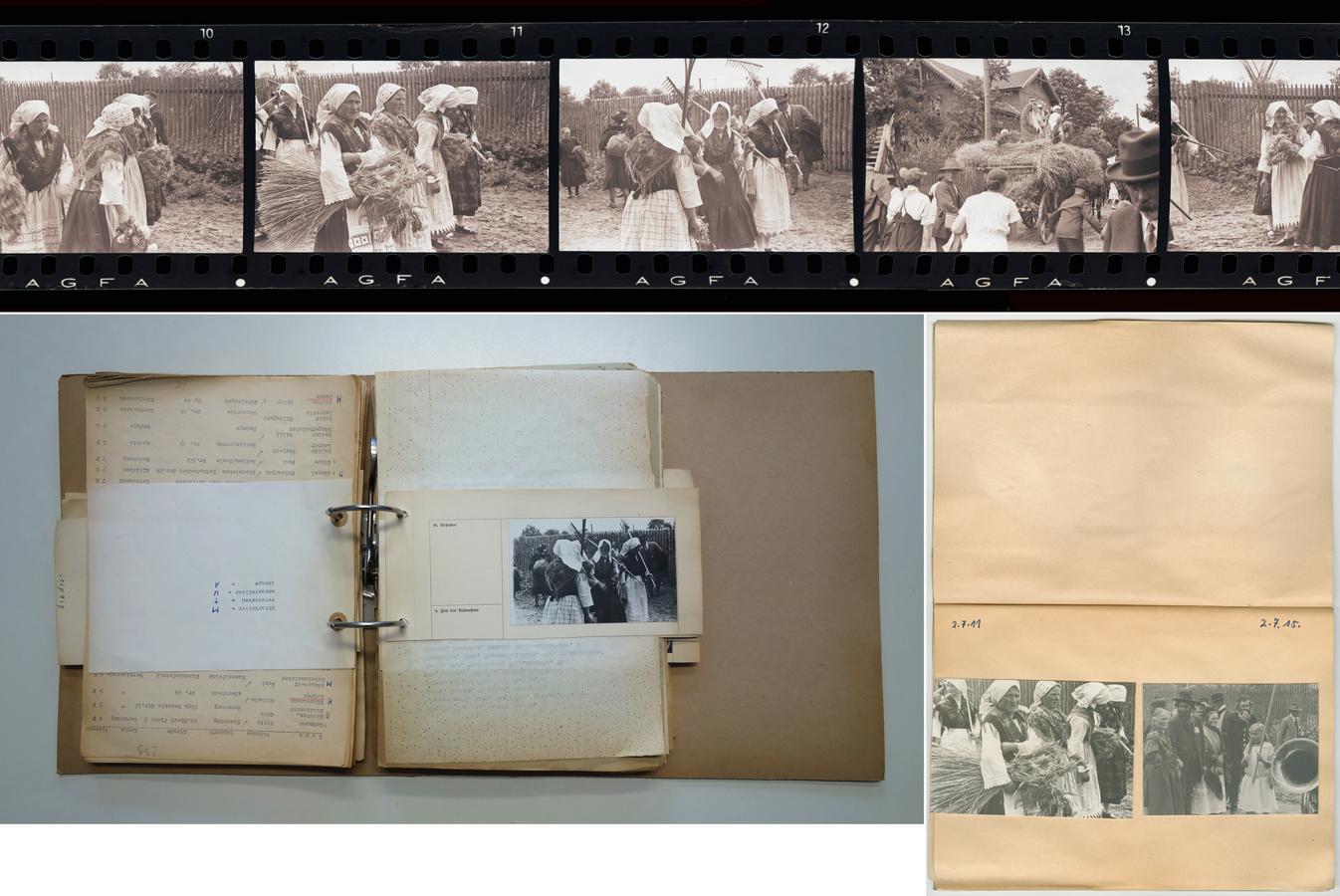

Second, apart from the record sheets, the main holding of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv is approximately 1,100 uncut negative films with approximately 35,000 black-and-white 35-mm pictures stored in 13 cardboard boxes. These negative films contrast with the format of mounted photographs in many ways. They have a materiality that makes it difficult to work with the images themselves. Only the act of rolling them out makes the actual image accessible and visible, but even then motifs are hard to see and need a trained eye. Furthermore, it is not practical to lay out or browse the negative films, or to compare series of single images.13 Even reprinting them in an essay like this one is problematic. Their format of 1.5 meters is oversized in relation to the limited space and limited numbers of figures in a printed paper. Showing them in their original format, that is, in full length and uncut, is only possible in an online repository—realized here by the digital visualization tool Hyperimage (see Fig. 13 in Hyperimage).

A special feature of negative films compared to single mounted photographs is the seriality within the format. Through the succession of one shot after another, series of photographs form linear and temporal sequences giving, for instance, an impression of the order of events, procedures, or arrangements. Film number 02/001 shown in Hyperimage displays sequences from the so-called Ochsenfest (festival of the ox) in the central German village Rotha in 1933. We see a historical parade with individual thematic groups dedicated to festivities, handcraft, rural life, political dates, or social groups like hunter or poacher.14 Since five other negative films (one is missing) are preserved, we know that film number 02/001 is neither the beginning of the documentation of the festival nor the only one showing this part of the parade. But its sequences form a kind of enclosed narration: the parade ends in a political speech with an unknown political leader standing in front of a crowd and flanked by men in SA uniforms as well as by a swastika.15

We are familiar with the iconography of each single image (parade, crowd, speech, and Nazi symbols). They can stand for themselves, but their grouping in one film generates a linear and temporal narration: the formation of the Volksgemeinschaft as a collective subject, a political actor, and a social community.16 Consequently, the narrative sequentiality of the negative films might contradict the intended representation of the Volksgemeinschaft. For example, the ducks seen on the village square between the people watching on film 02/001 perhaps create such a counter-narrative. We could imagine that the whole speech is accompanied by their quacking disturbing the intended staging of the Volksgemeinschaft. This kind of sequentiality is a remarkable difference to mounted photographs. Producing similar linear and temporal sequences with mounted single photographs is only possible by handling them, laying them out, and comparing, arranging, and rearranging them. On the other hand, it should be noted that this use of the film rolls as a series is not obvious and was suggested by the fact that the 1,100 boxes with the film rolls are the most remarkable, material, heavy part of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv, whereas most of the prints on record sheets are not preserved entirely (see below). We can imagine that originally the film rolls were just “archived” and people used and handled the prints as research material.

As the last example shows, different photographic formats generate different practices and routines in archives. At the same time, it is also the researchers and archivists who define the way photographs are handled and examined during their work. Photo-objects in archives could take on relatively standardized appearances, like at the KHI or the Art Library. In other archives, for example, at the Collection of Classical Antiquities or the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv, their physical format is more complex. However, they all share a history of constant and multiple changes in time and space, which is the focus of our next two chapters.

2.2 Formations: contexts, canons, and challenges

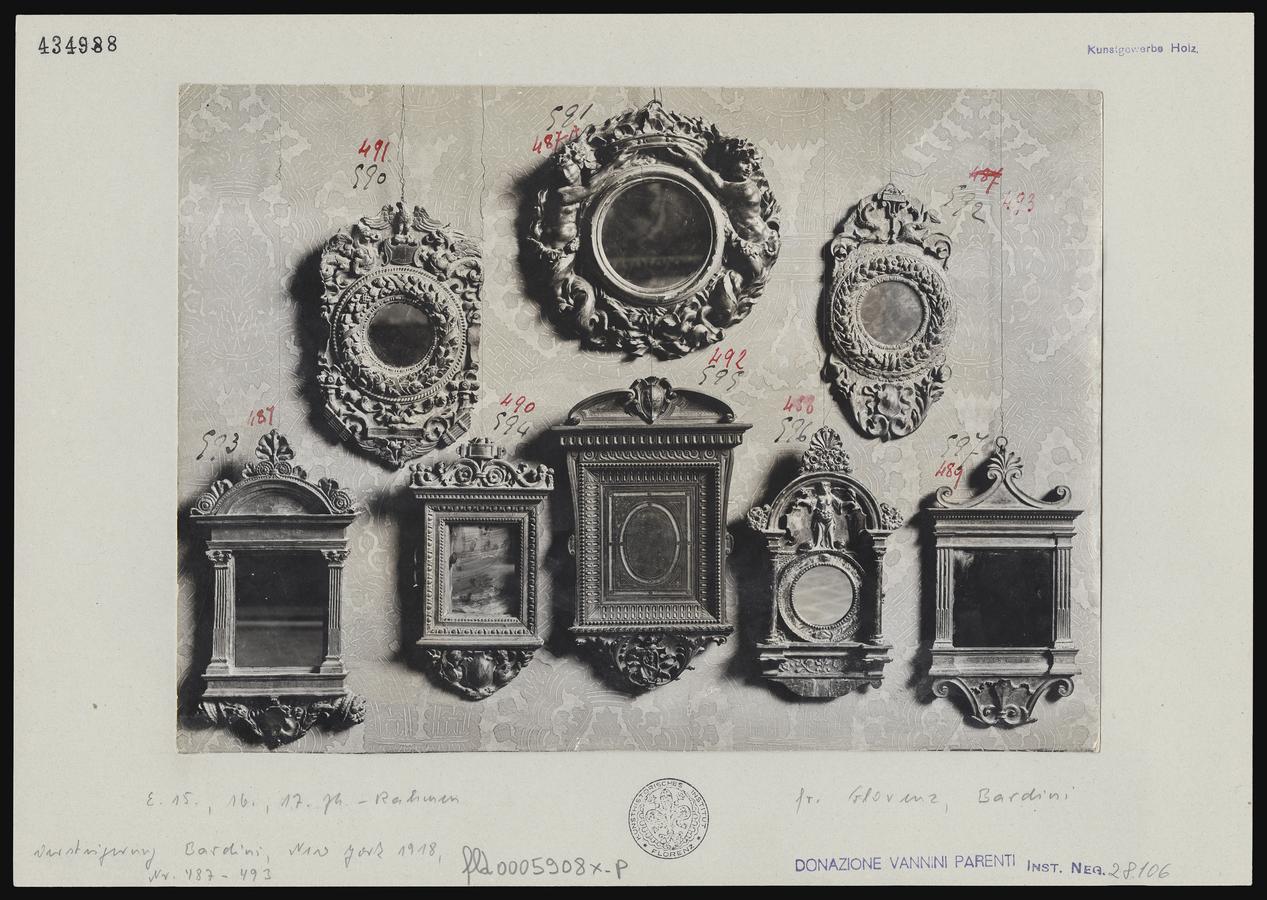

All photo archives are closely involved in processes of formation. In art history and archaeology, they are at the core of what defines the academic discourse (Caraffa 2011; Klamm and Wodtke 2017). Scholars looked at photographs more than they did at actual artefacts and in doing so, they were confronted with a prescribed selection of artworks and monuments.17 The Musée Imaginaire—according to the famous phrase by André Malraux (Malraux 1965)—of disciplinary knowledge is represented in a multitude of photographs and shows both the expansiveness and the boundaries of our disciplines (Geimer 2009; Locher 2011; Locher 2012). Processes of canonization took place while building up two of our photo archives in particular: the photographs in the Kunstgewerbe section at the Photothek in Florence and those in the Collection of Photography at the Art Library in Berlin both relate to an increased interest in the applied arts in the second half of the nineteenth century, which resulted in the worldwide emergence of industrial fairs as well as museums, schools, and collections specializing in the applied arts. Founded at the height of historicism, applied arts museums sought to convey historical and contemporary styles as well as techniques of production. The aim was to contribute to enhancing taste and the improving commercial and industrial production in order to overcome the separation of the arts and crafts. In this context, photographic collections were intended to take on exemplary functions in contemporary production.18

The photo archive which forms the basis of the Collection of Photography at the Art Library today was originally developed from the 1860s onward as a teaching repository to supply models and examples for the educational institute belonging to the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin. In addition to literature, this model and teaching collection also provided drawings, prints, and, of course, photographs of decorative art works and architecture to prospective artisans, architects, artists, and, as of the end of the nineteenth century, also to art historians (Evers 1994; Derenthal and Kühn 2010b). Acquiring representative photographs worldwide for this purpose was crucial. Peter Jessen (1858–1926), the first director of the Art Library, went on a trip around the world in 1913 that took him to the United States, Asia (China, Korea, and Japan), and Russia to learn about non-European art and acquire photographs, drawings, and prints (Jessen 1916–1917). In the U.S., Jessen bought 562 photographs directly from the amateur photographer Frank Cousins, based in Salem, Massachusetts (Jessen 1916, 46).19 These show colonial architecture—at the time at risk of demolition—on the east coast of the United States such as Daniel P. Parker’s Mansion, the house of a prominent Bostonian merchant and now a National Historic Landmark (see Fig. 15 in Hyperimage).20 Cousin’s photographs marked a significant change in the perception of colonial architecture as historic monuments and national heritage at the beginning of the twentieth century in the U.S. In 1913, for example, Cousins was commissioned by the Art Commission of the City of New York to document 50 buildings of historical importance before their demolition (Mason 2009, XIXf., 256). His photographs served the emergent preservation movement in North America as a decisive argument and, thus, they were very directly involved in processes of formation and canonization of a national heritage (Page and Mason 2004).

Unlike the photo archive of the Art Library, the Kunstgewerbe section of the KHI (see Fig. 16 in Hyperimage) did not primarily seek to provide artists and apprentices of the crafts with models for their work. Instead, the Florentine image collection as a whole was created to support academic research. This means that scholars, mostly art historians with specific research interests, would come to visit the collection, study, and compare photographs for their research. In this scenario, the applied arts section stands out from the other photographic holdings of the KHI (sculpture, painting, and architecture) regarding its age, size, and classification.21 Not only is it the newest section, having been introduced in early 1899, more than a year after the foundation of the KHI and the Photothek. With its roughly 37,000 photographs, it is also the smallest section. Furthermore, it is organized according to very particular categories. Whereas the sections of sculpture, painting, and architecture are classified by epochs, artists, and places, the applied arts follow a system that is based on materials and techniques, that is, noble metals, metals, enamel, wood, ivory, ceramics, textiles, stone cutting, etc. This difference in the classification system holds true not only for the KHI but is also characteristic of the structure of other photographic collections focused on the applied arts. The photographic holdings at the Art Library referring to artefacts of that category, for example, were organized according to materials and techniques first and foremost, and only secondarily according to epochs and places (General-Verwaltung der Königlichen Museen 1896, 41–75).

All of these aspects are closely related to the development of the applied arts in the nineteenth century. Notably, very similar to photography, works of the applied arts had a rather “uncertain” (Edwards and Lien 2014) status around 1900. On the one hand, there was an increased interest in the applied arts that resulted not only, as we have seen, in fairs, exhibitions, and museum foundations but also led to many publications on the socio-cultural role of this previously very much underestimated genre that, in public discourse, had always been stuck between the arts and the crafts; on the other hand, it was now, more than ever before, demarcated from the fine arts.22 Consequently, it is no surprise that the Kunstgewerbe section of the KHI is comparatively small and was treated differently from the other sections. Its organization goes back to image collections of applied arts museums such as that at the Art Library, where classification according to materials and techniques had been long discussed and was common practice by the turn of the century.23

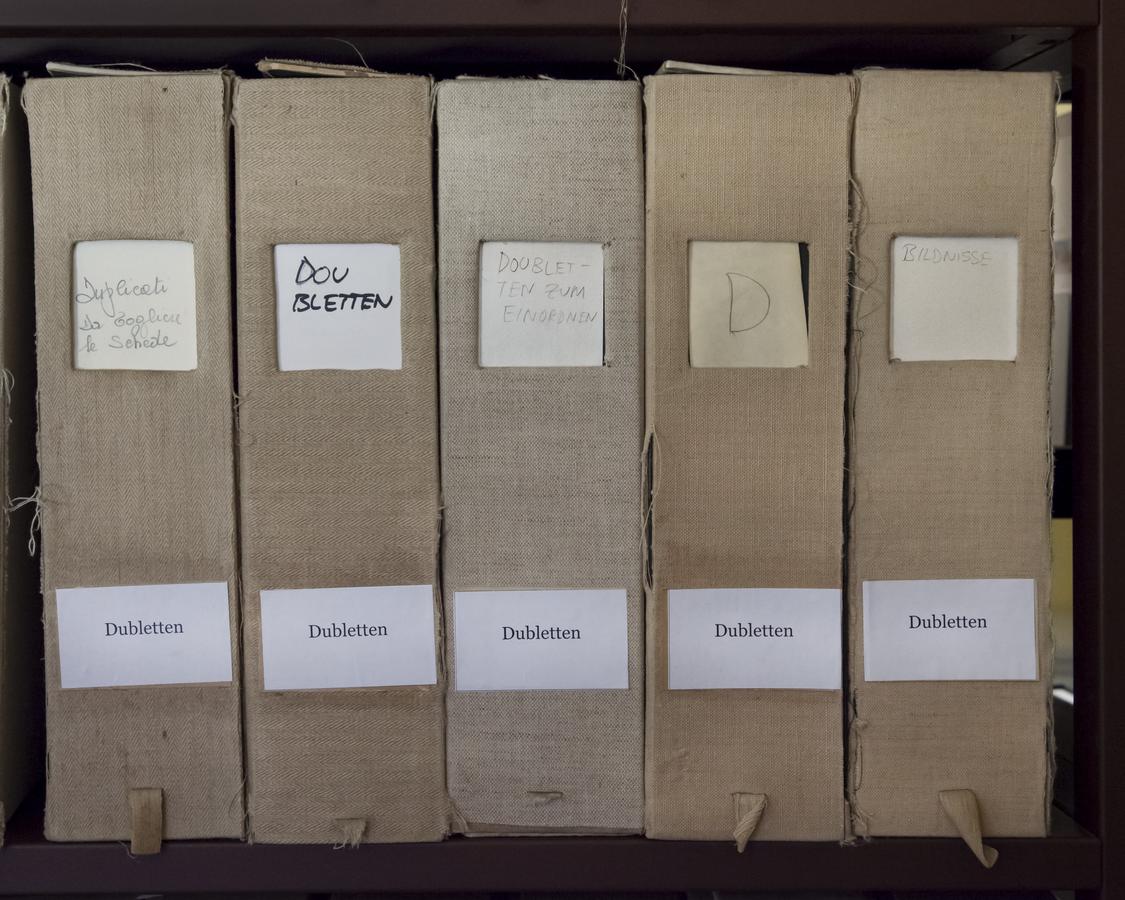

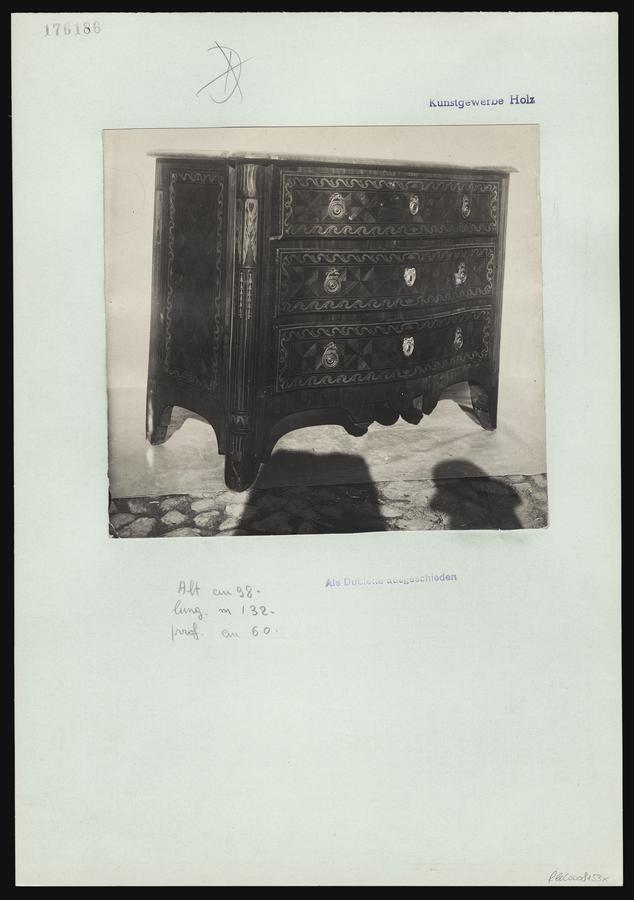

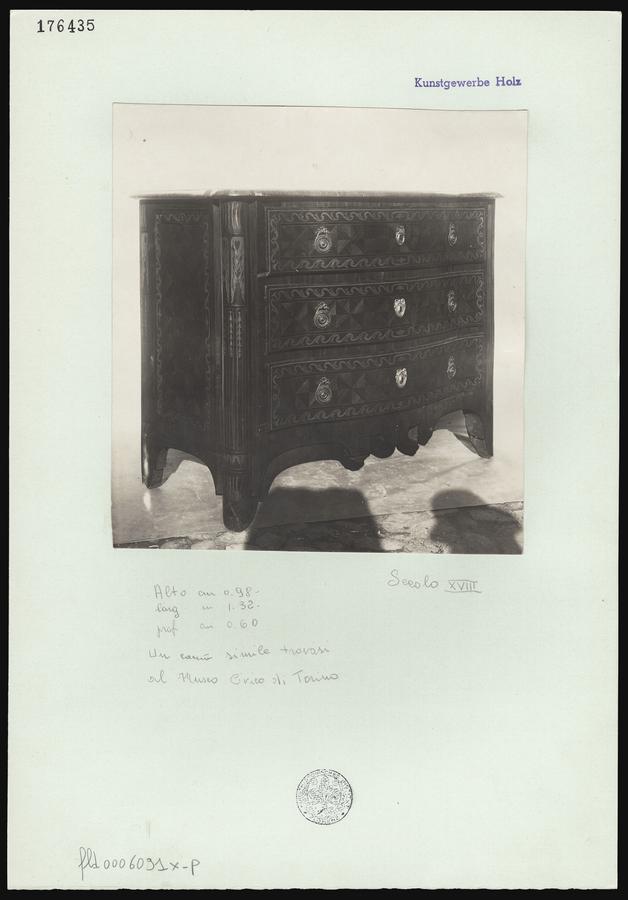

In every archive, there are what Elizabeth Edwards (2017) describes as “non-collections.”24 Most of our photo archives include seemingly “marginal” parts which stand outside the disciplinary canon and have been removed from the main holdings at some point in the past or have never been part of them, such as the “unsorted” (unsortiert) photographs at the Art Library or the “duplicates and various” (Dubletten und Varia) section at the Photothek of the KHI (see Fig. 17 in Hyperimage). From the 1920s onward, KHI archivists began to identify among the holdings of the Photothek photographs that were considered duplicates and thus to remove them from the collection. Stamped with the words “removed as a duplicate” (als Dublette ausgeschieden), these photographs were transferred into a separate section (see Figs. 18 and 19 in Hyperimage). They were kept here in order to be exchanged with the doubles of other archives. This ensured the material supply and dynamic flow of the archives as well as intellectual collaboration. The exchange of duplicates was not only common practice in most collections around 1900 but also systematically organized in academic circles such as the Exchange Society which were active in Europe around 1900 (Gianferro forthcoming). Over time, the duplicates section expanded to encompass all kinds of photographs that had not yet found their place in the collection and, hence, not been inventoried. This is the case with some photographs attributed to the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome, which had been lying dormant in this section for many years. With their retrospective incorporation into the archive in 2015, they underwent a drastic re-evaluation, as we shall see in the following chapter of this paper.

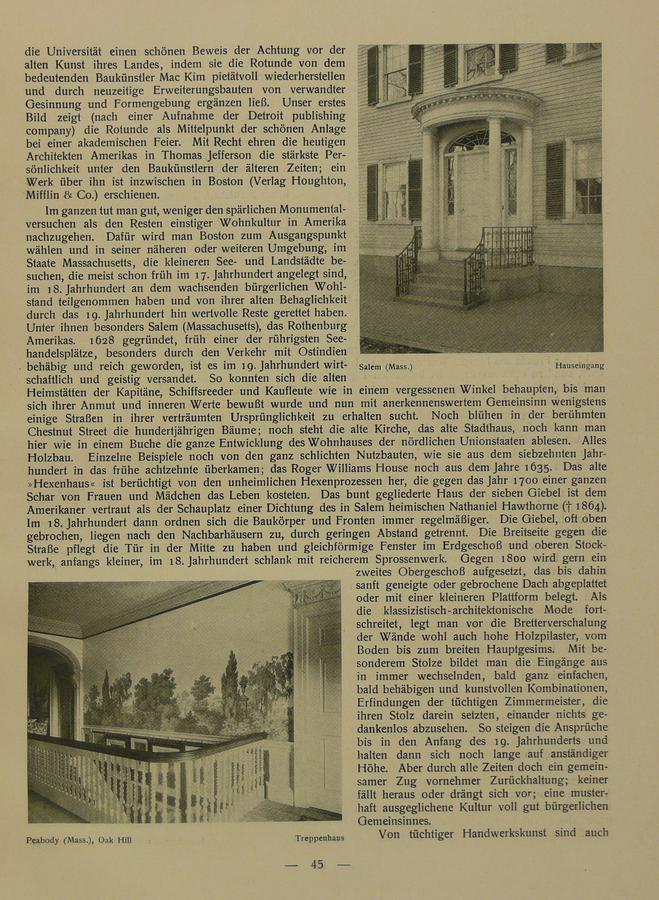

Processes of knowledge formation in photo archives play a crucial role in national identity politics (Caraffa and Serena 2015). For Jessen and in the collection of the Art Library, which was becoming more and more independent of the Museum of Decorative Arts, Cousins’ photographs were of interest because they depicted models and provided exemplary details for the development of the applied arts and architecture in German-speaking countries. Jessen included details about them in the report to his colleagues in the arts and crafts associations in Germany about interesting and exemplary American architecture and its decorative elements and interior design for German domestic residential buildings (Jessen 1916) (Fig. 20). The photographs thus became part of a debate about exemplary design and circulated as patterns for reproduction.

Fig. 20: Peter Jessen’s essay on the colonial style in the journal Kunstgewerbeblatt of 1916 with photographs by Frank Cousins.

Fig. 21

Fig. 22

Fig. hicollage2_1

Identity politics are also crucial for the formation of ethnographic photo archives. This is the case in particular with the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv. It was established by Hans Hahne (1875–1935), Director of the Museum of Prehistory and Director of the Regional Office for Prehistory in Halle/Saale, along with Heinz Julius Niehoff (1888–1947), a photographer and documentary filmmaker. For the question of disciplinary formation through archives, it is a key factor that Hahne, Niehoff, and their collaborators took most of the photographs themselves. The above-mentioned film number 02/001 illustrated that there were several photographers in the field that supposedly belonged to the team of Hahne and Niehoff (see again the film (Fig. 13) in Hyperimage, here, pictures 3 and 9). And we also see Heinz Julius Niehoff shooting a film (see again the film, Fig. 13, in Hyperimage, here, picture no. 34). This kind of self-representation (or self-archiving) in ethnographic photographs was widespread and could be interpreted as a way of stabilizing disciplinary authority: ethnographers recorded themselves as researchers in the field (see Fig. 21 in Hyperimage) to document that they had been “there” and witnessed something with their own eyes. It justified them writing about the “there” as well as marking their photographs as a result of field research.25 This is just one example of the many academic practices conducted with photographs. There is an inherent promise of objectivity that photographs are made not by human hands but by a neutral machinery depicting what is considered the “truth” (Daston and Galison 2010).

Forming a disciplinary representation was always an explicit task involving highly problematic cultural concepts of tradition, identity, or heritage. Since its founding in the early 1920s, Hahne/Niehoff used the photo archive (and other means) to pursue a very clear racist and nationalist agenda:26 As they understood it, Volkheitskunde was a science of the German people connecting Germanic prehistory, Volkskunde, and Rassenkunde. Their photographs, depicting regional customs in the former Province of Saxony, were intended to document the reputed uninterrupted racial and cultural continuity of a Nordic-Germanic people in central Germany. The festivity of Questenberg, called Questenfest (the parade in Rotha documented in film number 02/001 was a part of this), was consequently interpreted by Hahne as a Germanic “sun cult” (Ziehe 1996, 48–49).27 Under the canon of Volkskunde, which mostly comprised research on dwellings, traditions, religion, etc., Hahne and Niehoff portrayed people as what they considered “types”28 as well as representing so-called traditional festivities, costumes, artefacts, and architecture. These customs were understood, visually documented, and spatially cataloged as models of culture. Hence, the archive could be characterized as a typical version of ethnographic photo collections producing visual constructions of the “Other” as well as of the “Self.”29

In the case of the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv, this “Self” was understood as a social-political community: the Volksgemeinschaft.30 Today, the negatives are an interesting source for the analysis of everyday politics and the staging of the Volksgemeinschaft during the Nazi regime. But in terms of archival formation, it is important to note that it was Hahne and Niehoff’s intention to use the photographs as a tool for constructing the “German self.” Their archive was meant to produce and represent a politically propagated community that excluded the “Other.” What is then lacking are people and practices outside of the system as well as the violence, expulsions, and murders perpetrated under the Nazi regime. This absence was not accidental but the result of a racist and nationalist ideology intentionally deployed in the formation of the archive.

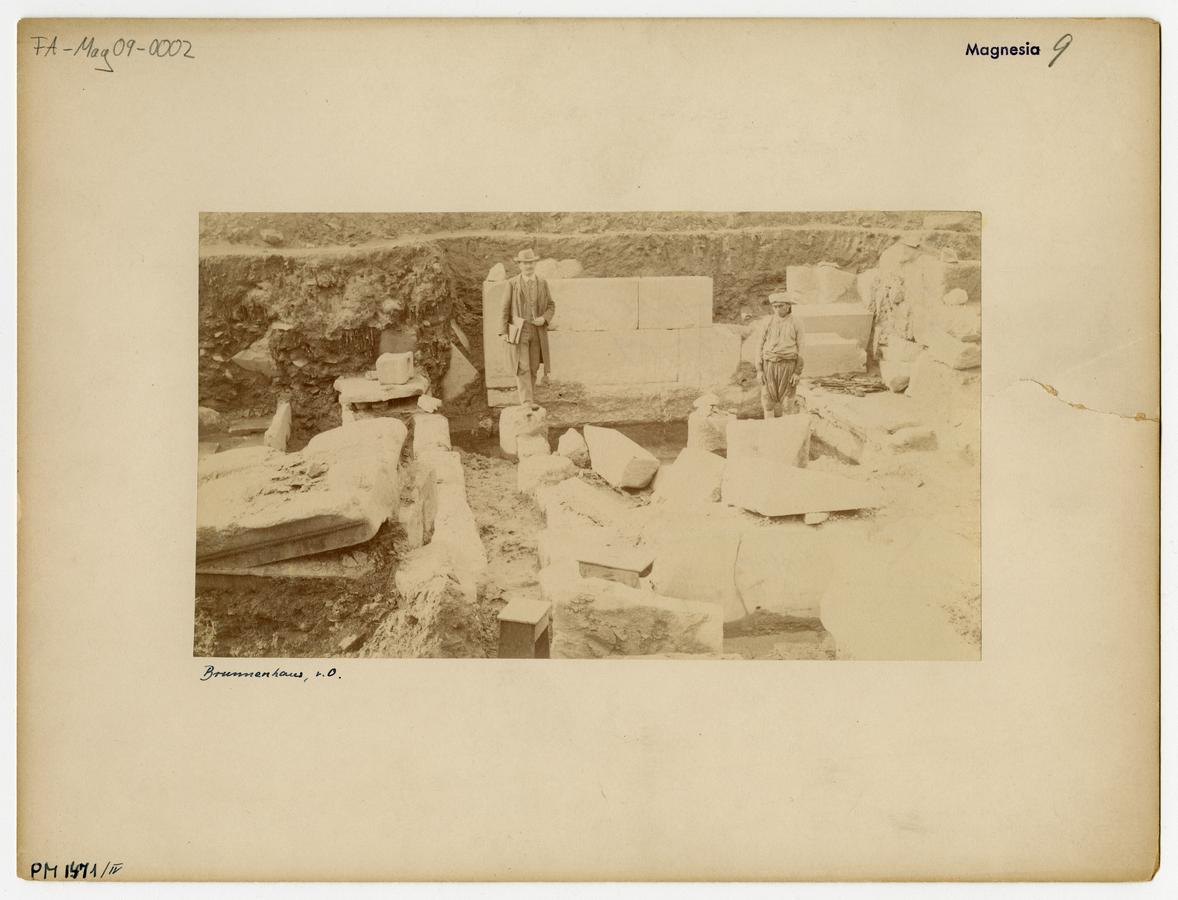

The archive of the Antikensammlung in Berlin is subject to an order that is fairly typical of the discipline of classical archaeology (Klassische Archäologie). Its photographs are divided into three sections representing research questions, methods, and practices of archaeological approaches (Alexandridis and Heilmeyer 2004): Most of the pictures show archeological objects such as vases, sculptures, and other categories to compare them with each other and with the actual objects in Berlin. The second section is composed of views of the museums’ showrooms and exhibitions. The third section follows a topographical order and is sorted by the names of cities or archeological sites. In particular, collecting and comparing pictures of the same objects was and is still today a very popular method of iconographic research—both in archeology and in art history. This method is also controversial, however, because it may defeat the idea of the double “objectness” of photographs and, hence, disguise their material qualities. Very often the photograph becomes the surrogate of the object depicted, drawing attention only to the image and not the whole three-dimensional photo-object with all its traces of use. And yet, to understand the formation of (archaeological) knowledge, it is also fundamental to identify and contextualize these material traces. They open up a multi-faceted and complex network that consists not only of human actors but also of archaeological fragments, numbers, and various media (see Hevia 2009, 79–119; Latour 2005).

In the topographical section, the photo-objects of Magnesia on the Maeander river in modern Turkey serve as an essential point of formation in the photo archive. The excavation at Magnesia took place from 1891 to 1893 and was headed by the above-mentioned Carl Humann (Humann, Kohte, and Watzinger 1904). On the basis of a few entries in the diary of the excavation and of Humann’s letters, it is very likely that he is also the author of the photographs.31 Fig. 7 shows a fragment of the frieze of the temple of Artemis in Magnesia. The picture was taken outdoors in front of the depot of the archaeological site. The negative held at the Antikensammlung (see Fig. 22 in Hyperimage) reveals that even better than the print. On the verso of the print (see again Fig. 7), someone wrote a note, which was transferred to the reverse of the cardboard after the photograph was mounted (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 23

Fig. 24

Fig. hicollage2_2

The notes pursue a certain order: the name of the ancient city “Magnesia a. M.” (am Mäander) is followed by a number that has not yet been attributed to a certain system (52) and the mention of the object depicted which is often used as the title of the image (Tempelfries). A second number (22a) refers to a counting system for the frieze that subsequently changed. For this reason, the number (28a) was added (compare Fig. 8 to Fig. 23 in Hyperimage). A short description of the circumstances is then followed by the date when the object was found (June 23, 1891) and concluded by Humann 4.7.91 (July 4, 1891). This particular part of the annotation does not refer to the taking of the picture but to the editing of the information at a later date.

Moreover, as mentioned above, the inscriptions on the back of the cardboard were copied by Otto Kern from Carl Humann’s original notes on the reverse of the photograph which would have disappeared with its mounting. Kern, an archaeologist and epigraphist who worked together with Humann in Magnesia and published the ancient inscriptions (Kern 1900), also kept the official diary of the excavation. Here, we find the very same styles in the handwriting of two different names, which confirms that the Magnesia cardboards were annotated on the back by his hand (compare Fig. 8 to Fig. 24 in Hyperimage).

The work at Magnesia followed a very structured and well organized order which is reflected in the photographs. This photo network was and is essential not only for interpreting the excavation in Magnesia but also for further research on the archeological site, including the preparation of publications on the subject. Apart from demonstrating how archaeological excavations were conducted around 1900, this photo network also gives important insights into the history of photographs as working instruments in the humanities.

Fig. 25

Fig. 25a

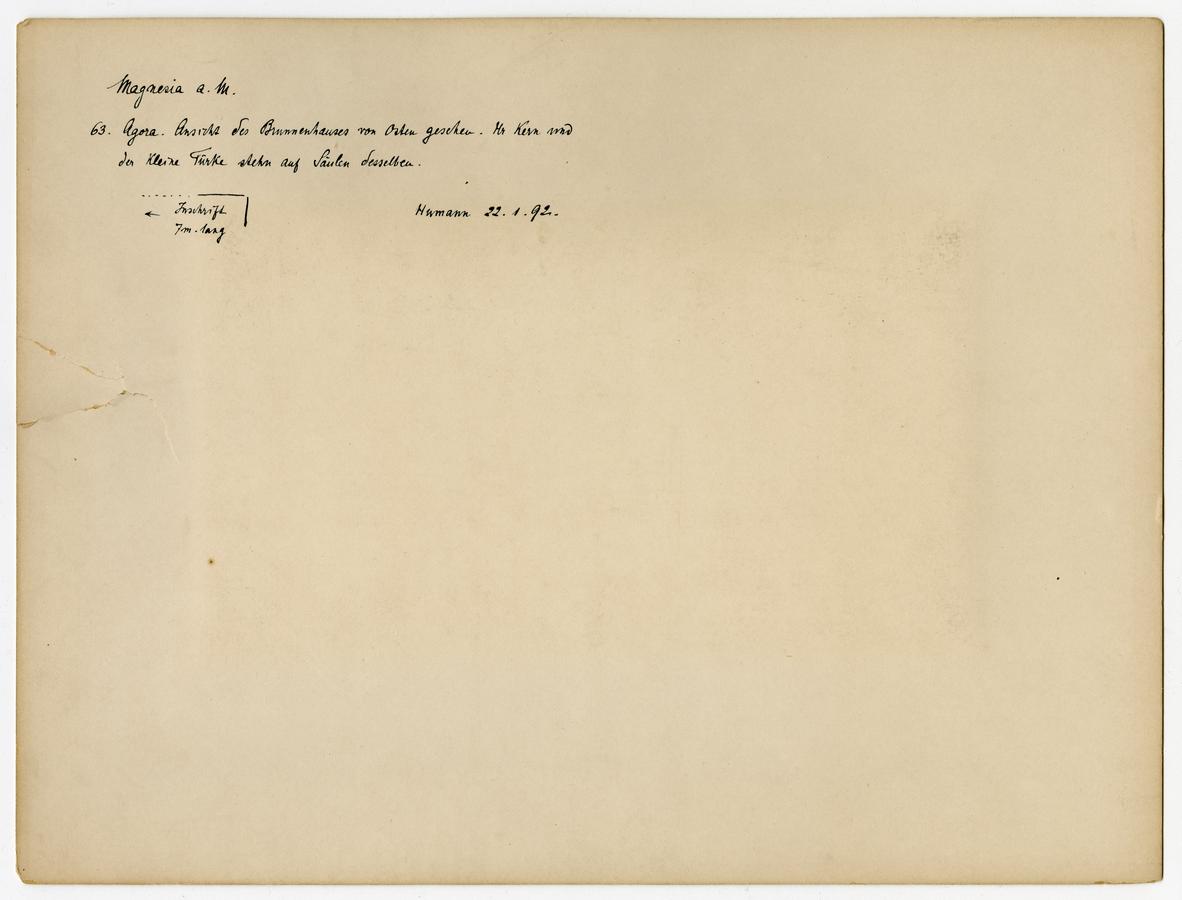

The excavation in Magnesia took place in the late nineteenth century. The photographs provide a starting point for reflection on archaeological work, methods, and practices in the contemporaneous political situations. These kind of issues are part of the postcolonial debate in archaeology, which has experienced a dramatic upturn since the 1990s.32 We do not have the space to enter into the debate here, but one short example will suffice to illustrate how photographs are entangled with politics. If we take a closer look at the Magnesia photographs, it becomes apparent that a variety of anonymous individuals can be seen in the images. One of them is identified as the “little Turk” (kleiner Türke, see Fig. 25 in Hyperimage).

The text says: Ansicht des Brunnenhauses von Osten gesehen. Hr Kern und der kleine Türke stehn auf Säulen desselben. (“View of fountain house from the east. Mr. Kern and the little Turk are standing on its columns.”) This young boy—as well as Hr. Kern—was used by the photographer as a marker to scale certain positions in some photographs of the agora at Magnesia. In this case, the excavator is mentioned by name and the other person just by his ethnical status. Both individuals are literally “placed” within the picture as markers. In fact, we know nothing about the boy. Was he a son of one of the workers, fascinated and interested in this engineering project and the idea of being pictured? Or was he a paid errand boy, placed there by the German photographer as part of his job? We do not have any evidence for one or the other assumption. The boy (or young man) stands slightly stiffly with his arms hanging close to his body. His head is bent forward and down a little. However, his gaze goes up and he is looking right into the camera, claiming a certain “presence” in the picture (Edwards and Morton 2015). Using people as markers for important positions at an excavation site is, to this day, a very common archaeological practice. The intention is to pinpoint archaeological finds that can otherwise hardly be distinguished in the excavated ground. In short, the photograph and it inscriptions leave us thinking about processes of appropriation and re-appropriation in the nineteenth century and today.

All of our archives show that no archive is neutral. Even seemingly “innocent” archives such as the Photothek of the KHI, the Art Library, or the photo archive of the Antikensammlung hold political implications. These are often underpinned by national identity politics that can be quite blatant but sometimes also relatively difficult to recognize. All photo archives are embedded in processes of decision making that are always dependent on what is considered to be of value in disciplinary discourses at a given time. Other parts of the archive may remain outside the canon of a discipline. But what is on the periphery and what is at the center can change. Processes of reassessment take place all the time in the histories of our archives, as will be discussed in the next section of this paper.

2.3 Transformations: continuing itineraries

The “itineraries” of photographs neither start nor end in our photo archives. Photographs lead multiple material “lives” before entering an institution. They also potentially continue to circulate afterwards. On the one hand, photographs are mobile within the institutional archives, and, on the other hand, they can also (but not frequently) leave the archive again. Thus, their “lives” do not end after entering an archive. Instead, their biographies continue. In this process, photographs are subject to various changes both to their physical appearance and to their forms of presentation. They literally undergo transformations; first, while entering the institutional setting and, second, while circulating within this and other settings. From their incorporation into the different archives onward, photographs accumulate traces of use and reuse. They are put into new reference systems, arrangements, and classifications which locate their meanings in new contexts. Below, each of our four archives is examined as an example of a different aspect of transformation that is, of course, also evident in the others. These could—very roughly—be characterized as material, descriptive, spatial, and social-political transformations.

Fig. 26

Fig. 26a

For the photographs in the Art Library, material and descriptive transformations were at the core of the process. What happened to the photo-objects there shows very impressively the importance of everyday practices of cutting in archives. When first acquired, Frank Cousins’ photographs, which had been bought by Peter Jessen as single prints, were mounted as pairs or even triples onto the cardboard carrier of the archive, reflecting the above-mentioned disciplinary typologies (see Fig. 26 in Hyperimage). They had been organized in folders (like the one in Fig. 4 shown in Hyperimage) according to the genres or typologies which were deemed to be most useful for practitioners in the arts and architecture: building elements such as front doors as well as ornaments and handcrafts were the main classification subdivisions of the photo archive.33

However, systems of classification in the archive then changed. After World War II, the Art Library’s photographic holdings changed its status to a repository for images with a focus on architecture.34 This new status was accompanied by the deaccessioning of many photographs of—for instance—paintings or antique vases and sculptures. We found photographs of the latter wrapped in their original folders from the Art Library in the photo archive of the Collection of Classical Antiquities. In other words, the photographs were redistributed according to the category of museum objects they represented among the different institutions (in possession of these kinds of objects) forming the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Fig. 27

Fig. 28: Salem (MA), Miss Susan E. Osgood’s Garden, supporting arches for climbing plants, Frank Cousins, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, left: 23.7 x 18.7cm (photo), right: 23.6 x 18.7cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

Fig. 29

First and foremost, however, this transformation meant radical physical changes to the photographs again, and literally intervention into their material basis through cutting (see Fig. 27 in Hyperimage). Some of the mounted photographic pairs were separated again (see Fig. 28). But even more dramatic cuts were envisaged, as is still visible from lines drawn on the cardboard and also on the photograph itself. These cuts were not only planned but also executed as other examples show where parts of the cardboard carrier and even parts of the photographic images themselves were cut off in order to make the mounted photographs fit into the new and differently formatted shelves to which the photographs were moved (see Fig. 29 in Hyperimage).

Fig. 30

Fig. 31

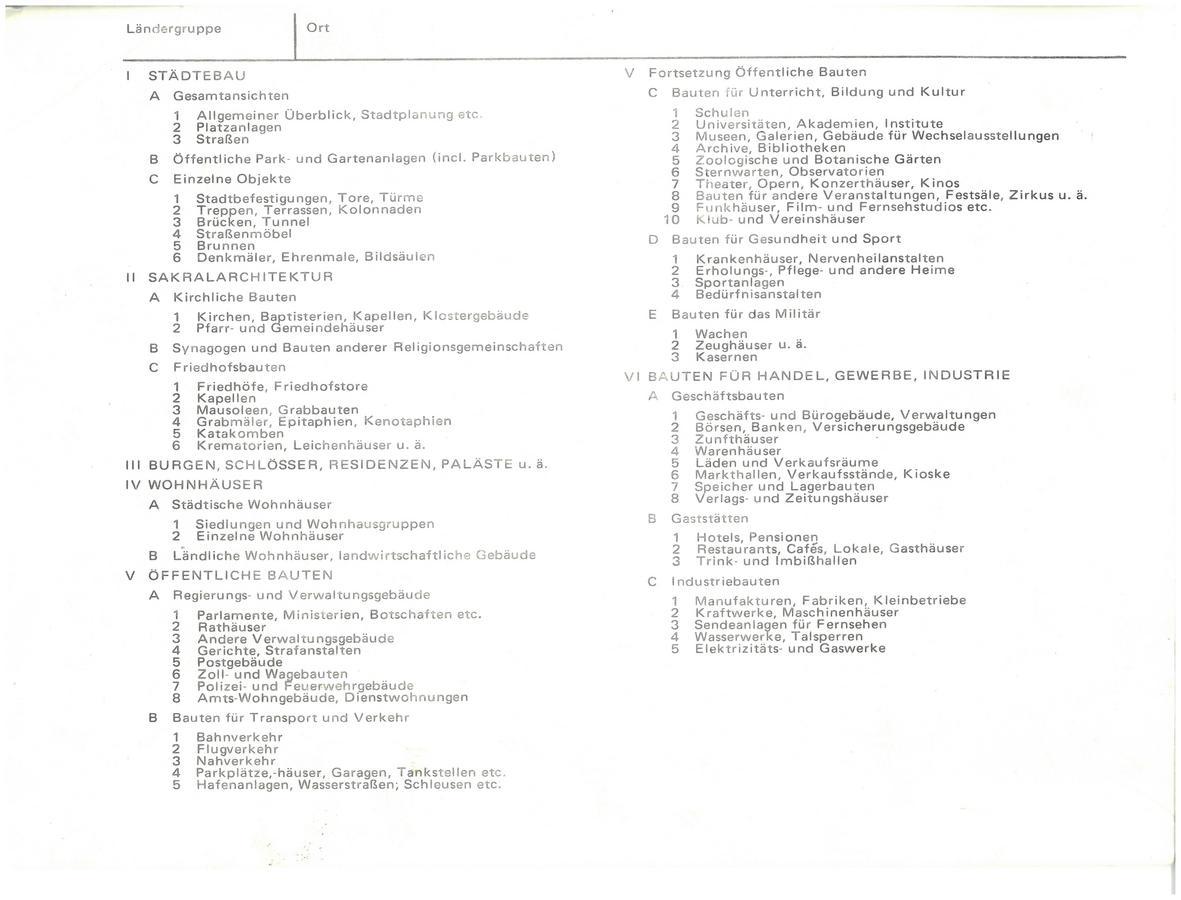

This physical transformation was accompanied by changes in the formats of knowledge and a move to different storage facilities and rearrangement in various groupings, too. In line with the new purpose of the archive as a repository for images focusing on architecture, the photographs were relabeled according to a new classification. This arrangement was organized following a typology of architecture with a focus on the function of buildings (see Fig. 30 in Hyperimage). Following this new system, the mounted prints were now classified with regard to topography and the function as well as the genre of the edifice depicted. They were each also stamped according to the new classification. Some of these stamps are even partly on the images themselves, indicating the scant regard for the photographs in their original form at the time (see again Fig. 29 in Hyperimage).

Yet the transformation of photo-objects in our collections does not stop. The most recent changes have occurred as a result of our own work and handling of the photographs, which is based on a re-examination of photographs as objects that also includes a re-evaluation. In the course of the twentieth century, and particularly with the institutional re-evaluation of the Art Library’s photo collection since the 1990s, the photographs’ status changed into a more musealized collection on the history of photography (Derenthal 2008). In this process, photographs by Frank Cousins were integrated into the exhibition A New View: Architecture Photography from the National Museums in Berlin, which opened in 2010 in the newly renovated exhibition hall at the Museum of Photography in Berlin (see Fig. 31 in Hyperimage).35 Cousins’ photographs were displayed framed with a passe-partout—as is standard practice in showing art photography—valorizing them as prestigious art objects and single images. Permanently set into a passe-partout, the photographs had to move boxes and shelves again. The former order of the archive was disrupted once more. This transformation of the photo-objects is part and parcel of a changing status of such photo archives as a result of increased historization and musealization.36

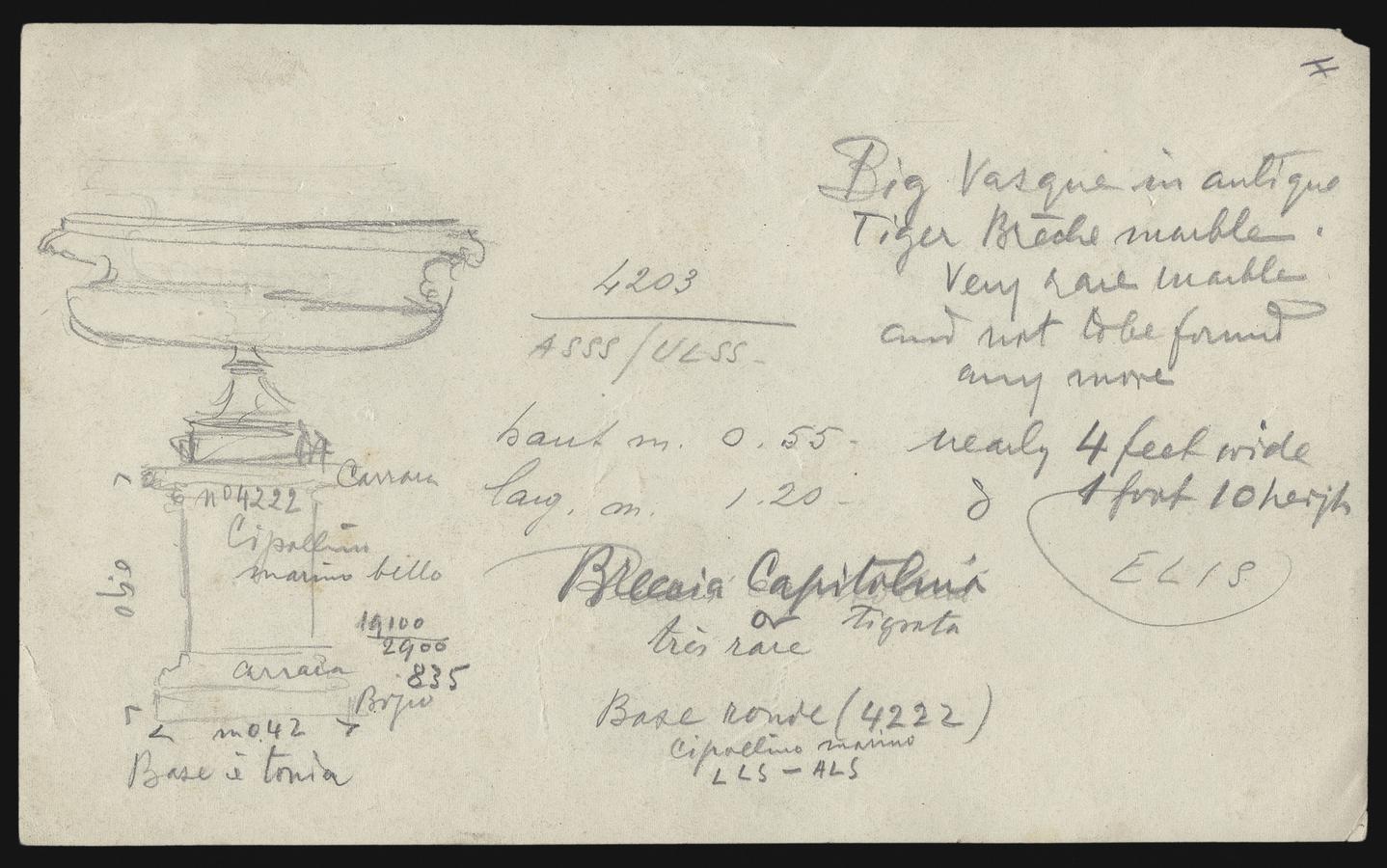

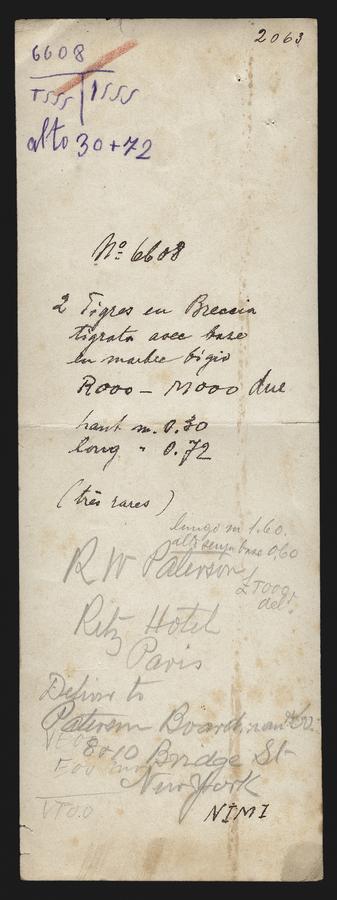

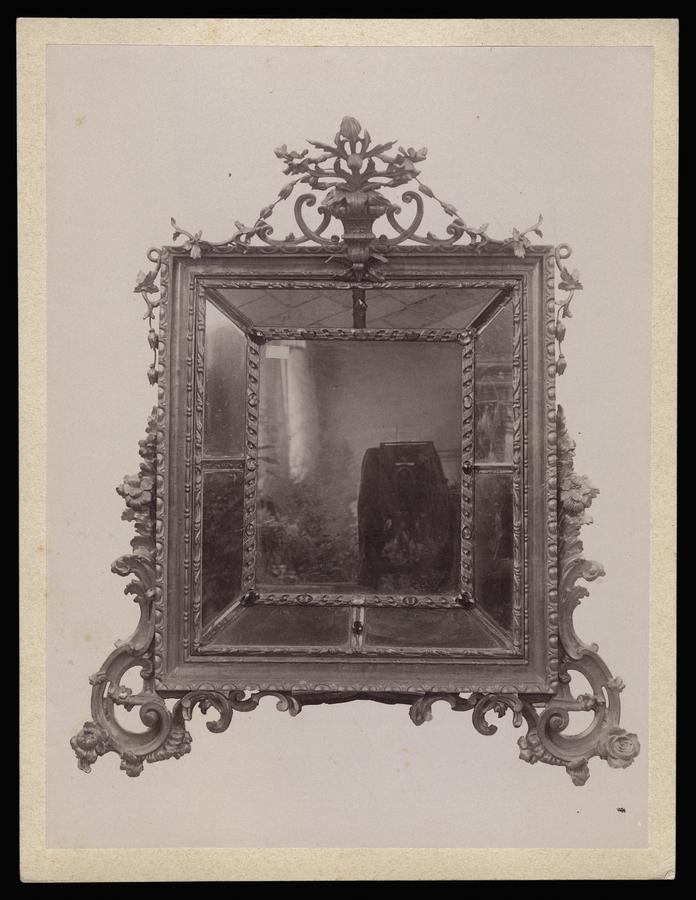

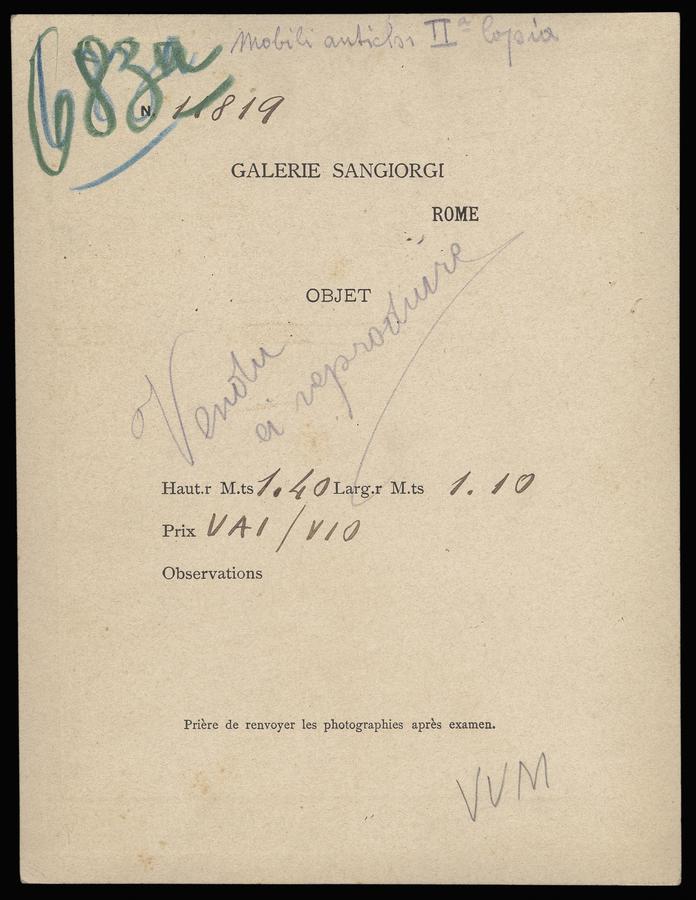

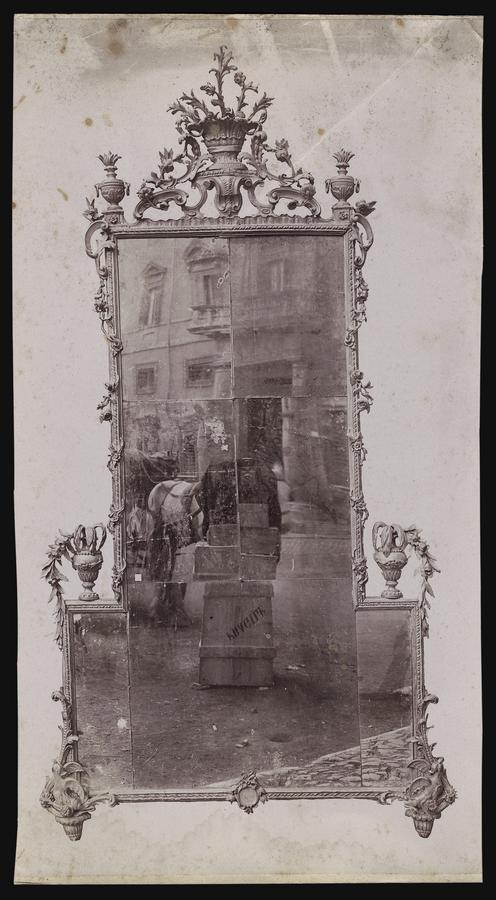

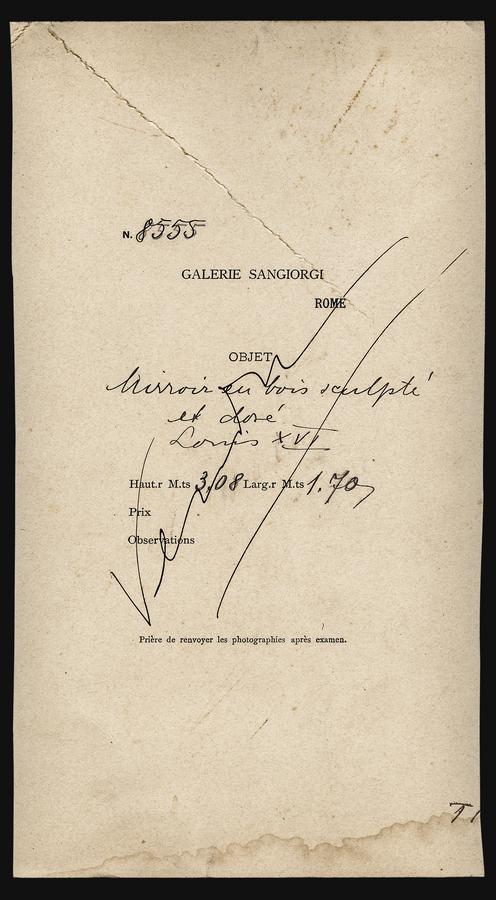

Similarly, the photographs of the Galleria Sangiorgi at the KHI (see Fig. 32, to unbox the photographs see Hyperimage) were re-evaluated several times in the course of their journey. Before they were rediscovered amongst the duplicates at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, these photographs played an essential role in the workflow of the auction house. The Galleria Sangiorgi was founded by the Italian entrepreneur Giuseppe Sangiorgi (1850–1928) at the Palazzo Borghese in Rome around 1892 and soon became one of the largest and most successful auction houses with many prestigious clients.37 Its photographs were part of a structured business with different departments and offices in various international locations circulating amongst staff, agents, artists, photographers, experts, and collectors. Before they even entered the KHI, they were already bureaucratic hybrids and mobile objects between art, archives, and commerce. The auction house closed in 1970. However, the journey of the photographs does not end here. We do not know exactly how they entered the Photothek of the KHI.38 Once there, they underwent another spatial transformation: with their rediscovery in 2015, the Sangiorgi photographs were inventoried—but not as part of the main holdings. Instead, they traveled to the Cimelia Photographica section (Caraffa 2012) where the eldest, rarest, and materially most interesting photographs are kept. As a result of this, they were subject to an enormous shift in perceived value from the “non-collections” of the archive to the photographic “treasures.” This practice is meant to contribute to the appreciation of analog photographs and photo archives through the accentuation of their material richness. However, at the same time there is also a risk of putting certain photo-objects on a pedestal and thus separating them from their archival contexts.39 This is where the concept of archival “ecosystems” comes in, flattening traditional hierarchies and highlighting the importance of each single photograph in its own right (Edwards 2017; Caraffa 2017).40

Fig. 32: Box and photographs attributed to the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome in the “duplicates” section of the Photothek, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2017.

Fig. 32a

Fig. 32b

Fig. 32c

Fig. 32d

Fig. 32e

Fig. 32f

Fig. 32g

Fig. 32h

Fig. 32i

Fig. 32j

Fig. 33

Fig. hicollage2_3

This practice also reflects how research interests have changed over time. Whereas, originally, users would consult photographs mainly for their visual content (to compare works of art), they are now increasingly focusing on the photographs themselves as material objects as well as on the history of photo archives. Within our projects, these photographs are now, as Edwards (2011a) has argued for a long time, resourceful objects which can and should be studied for their historical and social contexts. This also means that photographs become historical objects in their own right, among others in the history of our disciplines. Moreover, the “rediscovery” of the Sangiorgi photographs stemmed from a curiosity for the uncanonical, an affective search for photo-objects that cross archival boundaries, classifications, and typologies. Thus, affect is just as much an archival reality as classification systems and card catalogues (Edwards 2012; Edwards and Morton 2015).

The photo-objects in the Collection of Classical Antiquities in particular are vivid examples of the never-ending transformation of photographs in archives. To this day, photographs of Magnesia on the Maeander river are used for further research with annotations and numbers constantly added. They are permanently handled and used, arranged, and rearranged.

For example, in 1902, shortly after Carl Humann had died in 1896, but before the leading book about Magnesia was published (Humann, Kohte, and Watzinger 1904) and the first Pergamon Museum opened (1910), Emil Herkenrath wrote his PhD about the friezes of the temple of Artemis (Herkenrath 1902). When preparing this work, he used photographs excessively: he added numbers in pencil that count the figures of the frieze, while the blue “2” refers to a system which reconstructs the fragments of the frieze discovered within its ancient order (compare Fig. 7 and Fig. 33 in Hyperimage).

Furthermore, the frieze was not published through photographs but through drawings, which—in turn—were based on the photographs.41 This is evident from a little note on the side of the cardboard reading: “trace the part in red” (das rot unterstrichene durchpausen). Other indicators are the small drawings beside the photograph and the small holes made by pins used to fix the tracing paper. The fragment of the frieze marked with a red line was brought to Constantinople (Mendel 1966, 380). The other ended up in Berlin and is now exhibited in the Pergamon Museum.42

Fig. hicollage2_4

Fig. hicollage2_5

Fig. hicollage2_6

The network continues to expand. On August 23, 1938, the negative of this photograph was registered in the index for negatives as PM 1443 (see again Fig. 22 in Hyperimage). On this date at the earliest, the PM number and also the reference to the publication was added on the cardboard, according to the handwriting.

In his 1976 publication on the frieze of the temple of Artemis in Magnesia, Abdullah Yaylali assumes that the photographs and the documentation material might be missing (Yaylali 1976, 13).43 Since they were kept at the Old Museum in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), he had no access to them and apparently no knowledge as to their existence. Hence, he left no traces on the photographs. Only a mention in the book reveals his absence from the archive. It is a negative result leading to a kind of non-transformation of the photo-objects: although there is no visible material change to the photographs as a result of Yaylali’s assumption, it does change their meaning and their status from existing objects to absent ones and therefore absent knowledge.

The “Photo-Objects” project began in 2015. It soon became clear that it was not very easy to handle the selected photographs from Magnesia: they did not have their own identification number within their system. Only the “shelf number” gave a rough idea of their position within this system; the single cardboards only had the number of the negatives or their inventory convolute. If there were more photographs in one convolute or more prints from one negative, it was not possible to select the one being searched for. Therefore we, the project team, decided to allocate ID numbers to every single photo-object and note them on the top left-hand corner of the cardboard (see again Fig. 7, top left-hand corner) (Wodtke 2016; Klamm and Wodtke 2017). Thus, adding our inscriptions and also our personal handwriting to a selected number of photo-objects as part of this project constitutes a further generation of researchers. And so the transformation continues.

The examples of the Art Library, the KHI, and the Collection of Classical Antiquities all show that photographs were physically transformed over and over again, also in terms of their arrangement, use, and evaluation. They took different routes and were often dispersed. The various assessments of the photographs as part of their subsequent incorporation into different collection contexts is of major importance in the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv, too. One of the main transformations of the archive and its photo-objects resulted from the end of the Nazi regime and the reordering of the institutional landscape in the GDR in the 1950s, leading to a centralization of responsibilities of the scientific and cultural institutions. In the light of this, it was decided that the Halle Museum of Prehistory should collect and display only prehistoric objects. Therefore, its entire ethnographic collection was handed over to East Berlin’s Volkskunde Museum (now the Museum of European Cultures) in 1953, including the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv. From there, some of its contents—the negatives and most of the 11,200 record sheets—were moved to the GDR Academy of Sciences in 1956. Here, the holdings were dealt with in very different ways. While the negatives were largely forgotten, the record sheets were cut and reused by members of the Academy: some of the prints were cut out and repasted into a card catalogue for ethnographic research on regional customs, traditions, and community in East Germany. The photographs of the above-mentioned film no. 02/001, for instance, were integrated into three cards in a section called festivities around Pentecost. Moreover the rearrangement and recombination took place on several levels: individual photographs of different Rotha films were mixed and grouped together according to their motifs (see Fig. 34). In this new compilation, the original sequences of the films as well as those of the festival were ignored. Instead, the index cards introduce a new order of comparison, while focusing on the single image. Scrolling through the different pages of one index card gives an impression of the seriality of motifs and figures of the festival.

Fig. 34: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, index card with photographs from former record sheets, Heinz Julius Niehoff, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie – Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Fig. 35

Fig. 36

As can be seen in Fig. 34, the reuse of pictures with Nazi symbols or the Hitler salute (in other images) seems not to have posed a serious problem in the early days of the GDR. Even the end of the Rotha film showing the speech with men in SA uniforms and the swastika is mounted on one card (see Fig. 35 in Hyperimage). Hahne/Niehoff’s descriptions on the record sheets were also transferred (see Fig. 36 in Hyperimage). Furthermore, those cards were merged with those resulting from research and collecting activities in East Germany in the late 1950s. It is obvious that the Hahne/Niehoff photographs were easily integrated into research projects in the early GDR, demonstrating a continuity of research between National Socialist and 1950s Volkskunde.

Fig. 37: Divider / Piece of a former record sheet, Heinz Julius Niehoff, in folder no.1 of Drescher und Dreschen, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie – Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Fig. 38

Fig. 39

Fig. hicollage2_7

In the 1960s, the vast majority of the record sheets were simply reused as paper objects—as dividers in administrative files, in personal documents, and in research materials. Cut-up record sheets were also utilized as placeholders for books lent out from the library of the Institute of Volkskunde at the Academy of Sciences. There seems to be no logic determining which of the photographs from the sheets were integrated into the index cards and which of them were used as dividers. The Rotha film no. 02/007, for instance, was incorporated in both: one index card is made of photographs of this negative film only. We also discovered one record sheet cut as a divider in the files on Drescher und Dreschen, a 1965 survey on threshers and threshing, as part of research on agricultural equipment and work by Rudolf Quietzsch and Wolfgang Jacobeit (see Fig. 37, compare this with Figs. 38 and 39 in Hyperimage).

Here, photo-objects became mere objects which should refer to nothing (but, of course, they did). As paper objects, they were integrated into different contexts of collecting and managing: from research material to administration files to personal records and library loans. This reuse might be a result of a lack of paper in the GDR. But it could also be interpreted, on the one hand, as a break with the National Socialist history of the discipline (Hägele 2005), and on the other hand, as part of a disciplinary shift of Volkskunde toward everyday practices devaluing old canon photographs. In both cases, with the reuse of photographs in index cards and as mere paper objects, the original photo archive was not protected. Instead, the archive was used as a form of “quarry” (Tschirner 2010, 105) where people could take out whatever they wanted. As a result, the Hahne-Niehoff-Archiv becomes a “distributed entit[y]” (Morton and Newbury 2015, 9) with the photo-objects moving between locations and socio-political contexts.

When we look at these examples, it becomes clear that transformation in archives can go hand in hand with both valorization and degradation. Photographs can turn into “mere” paper objects or the photo-objects can become treasures. Procedures and practices of working in archives may vary in time, but what seems to be certain is that the transformation of the photo-objects continues to this day and will also continue in the future—not least between the analog and the digital environment, which has not been the subject of our paper but which, of course, plays a fundamental role within the archives we are dealing with. Photographs in archives move—through different boxes, shelves, folders, etc.—as part of these transformations. They do not remain in one place. We hope to have shown that these transformations through different practices in the photo archive itself determine the experiences both with and of photographs.

2.4 Conclusion

All four archives incorporate a multitude of functions and purposes. The photographs continue to be mobile and haptic objects but they are viewed differently today. In their previous “lives,” these photo-objects would be presented in various formats, picked up, handled, turned around, annotated, numbered, circulated, cut into pieces, punched, and glued together—to name but a few common photographic practices. Nowadays, their handling is much more cautious since it takes place in a clearly defined institutional or museum context. Photographs become part of the historiography of those institutions and the disciplines they represent.

This is also reflected in the changing perspective on photographic collections such as ours: whereas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, art historians, archaeologists, and ethnologists mainly looked at photographs in order to learn more about the artworks, artefacts, or events and people depicted in them, today we are also interested in the photographs themselves as research objects. This does not mean that they are put on a pedestal, never to be touched again. They are still being passed from hand to hand, box to box, room to room. But during this process, they leave a trace of their material history, their biography, in our minds, senses, and pens. In a way, these photographs are epistemological hybrids: entering, leaving, and reentering the archive again and again, each time according to their attributed status in the academic narrative and archival practice. They are reservoirs of knowledge representing disciplinary history as well as its relationship with photography, also shedding light on the history of photography in general, which is no longer just a history of images, but also a history of three-dimensional dynamic photo-objects.

Despite their compulsory standardization, archives are never static entities. Every once in a while, the apparent synchronicity of the archival order is interrupted by discords. These are usually the most revealing: unexpected irregularities, problems, and insecurities make us doubt, think about, and question our fixed beliefs. For a long time now, these beliefs have been underpinned by the rhetoric of objectivity: the assumption that archives are neutral spaces of documentary truth and that photographs are visual representations of some form of reality. Although we know better by now, this rhetoric is still frequently used to undermine the value of analog archival material as well as research related to it—when space is required and funding is hard to come by, it is often the archives that suffer, even more so the photo archives (not to mention slide collections). However, if we watch out for archival interruptions and technical problems, if we look at the margins of the archives, instead of ignoring them, it becomes clear that objectivity is a mere construct and that archives are in fact extremely versatile spaces.

2.5 List of Figures

• Fig. 1: Cardboards and boxes from the Kunstgewerbe section of the Photothek, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2015.

• Fig. 6: Salem (MA), windows in Chestnut Street 26, 29, and 27, Frank Cousins, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, c.1900, left: 20.3 x 16.1 cm (photo), center: 20.4 x 12.4 cm (photo), right: 20.4 x 14.2 cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

• Fig. 7: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 20.2 x 11.3 cm (photo), 21.6 x 28.5 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. FA-Mag04-0001, neg. no. PM 1443.

• Fig. 8: Verso of Fig. 7: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 21.6 x 28.5 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv.no.FA-Mag04-0001, neg. no. PM 1443.

• Fig. 11: Ivory relief of Baptism of Christ, unidentified photographer, c.1900, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 27.6 x 17.8 cm (cardboard), exchange with the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, inv.no.240986.

• Fig. 12: Record sheet of a photograph from the Ochsenfest in Rotha, in original folder, Heinz Julius Niehoff, 8.9 x 13.6 cm (photo), 34 x 24 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum Europäischer Kulturen, photo archive (Hahne collection), folder “Friesdorf,” photo: Wiebke Zeil, 2015.

• Fig. 20: Peter Jessen, “Reisestudien. III. Der amerikanische Kolonialstil,” in: Kunstgewerbeblatt NF 28/3 (December 1916), p. 45 with photographs by Frank Cousins, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek.

• Fig. 28: Salem (MA), Miss Susan E. Osgood’s Garden, supporting arches for climbing plants, Frank Cousins, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, left: 23.7 x 18.7cm (photo), right: 23.6 x 18.7cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

• Fig. 32: Box and photographs attributed to the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome in the “duplicates” section of the Photothek, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2017.

• Fig. 34: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, index card with photographs from former record sheets, Heinz Julius Niehoff, silver gelatin paper, left: 7.4 x 11.8 cm (photo), right 9.4 x 7.3 cm (photo), 29.8 x 21.1 cm (cardboard, open), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Archiv der Landesstelle für Berlin-Brandenburgische Volkskunde, B.I.2.4.14.-3, “Feste um Pfingsten,” scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.

• Fig. 37: Divider/piece of a former record sheet in folder no. 1 of Drescher und Dreschen, Heinz Julius Niehoff, 7.9 x 12.8 cm (photo), 11.2 x 24 cm (cardboard), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Archiv der Landesstelle für Berlin-Brandenburgische Volkskunde, B.I.2.2.6.3.-01, divider no. 18, photo: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.

2.6 In Hyperimage only:

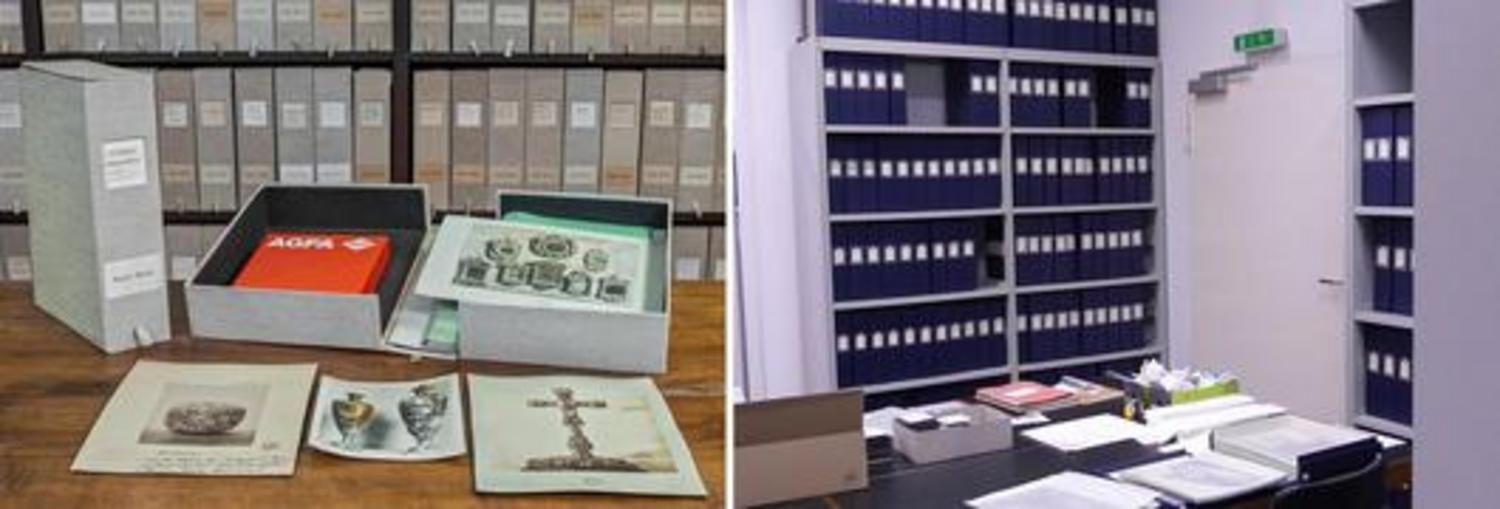

• Fig. 2: The “Image Archive” from the Collection of Photography at the Art Library with its boxes, digital photograph, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, photo: Andras Veg, 2015.

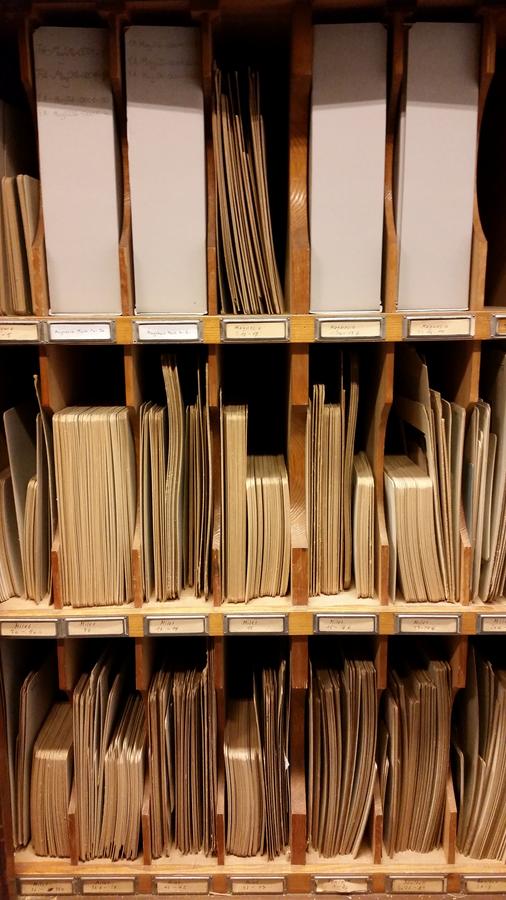

• Fig. 3: Cabinet 5b: Topography, “Magnesia” in the photo archive at the Collection of Classical Antiquities (Antikensammlung), digital photograph, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Altes Museum, photo: Petra Wodtke, 2015.

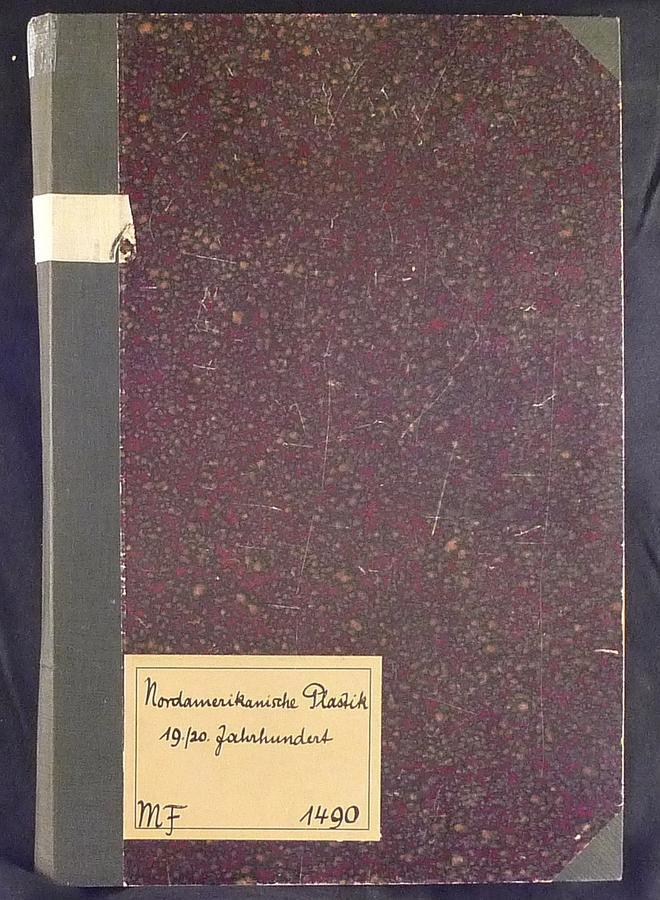

• Fig. 4: Folder “North American Sculpture, 19th–20th century,” which was used for ordering and keeping the photographs in the Art Library’s archive up until the 1960s, digital photograph, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, photo: Andras Veg, 2015.

• Fig. 5: Mirror frames, unidentified photographer, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, 18.3 x 25.4 cm (photo), donation by the Vannini Parenti family from the collection of Elia Volpi, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, inv.no.434988.

• Fig. 9: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, taken 1891, printed in the 1930s, collodion paper on cardboard mount, 20.5 x 13.9 cm (photo), 24 x 30.8 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv.no.FA-Mag04-0004, neg. no. PM 1443.

• Fig. 10: Fragment of the Artemision’s eastern frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Atelier Giraudon, Paris, before 1901, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, 26.3 x 19.8 cm (photo), 24.1 x 31.1 (cardboard), Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, convolute no. 979, inv.no.FA-Mag05-0005.

• Fig. 13: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, film no. 02/001, Heinz Julius Niehoff, Agfa b/w film/edited reversed digital scan, 3.5 x 150 cm, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.

• Fig. 14: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, sequence of film no. 02/004, Heinz Julius Niehoff, Agfa b/w film/reversed digital scan, 3.5 x 16.6 cm, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.

• Fig. 15: Boston (MA), Daniel P. Parker’s Mansion, staircase (left), stairhead (right), Frank Cousins, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, left: 24 x 18.6 cm (photo), right: 23.9 x 18.8 cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

• Fig. 16: The Kunstgewerbe section of the Photothek in Palazzo Grifoni, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2015.

• Fig. 17: Boxes containing “doubles” in the Photothek, digital photograph, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, photo: Stefano Fancelli, 2015.

• Fig. 18: Chest of drawers (with shadow of camera and head), unidentified photographer, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount stamped “removed as a duplicate,” 16 x 17.3 cm (photo), Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, inv.no.176186.

• Fig. 19: Chest of drawers (with shadow of camera and head), unidentified photographer, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, 17.4 x 16.2 cm (photo), Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz – Max-Planck-Institut, inv. no. 176435.

• Fig. 21: Niehoff in a procession, unidentified photographer, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, 8.2 x 13.2 cm (photo), 29.8 x 21.1 cm (cardboard, open), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Archiv der Landesstelle für Berlin-Brandenburgische Volkskunde, B.I.2.4.14.-2, “Lätare,” scan: Wiebke Zeil 2016.

• Fig. 22: Fragment of the Artemision’s western frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, glass negative, 21 x 13 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, neg. no. PM 1443.

• Fig. 23: “Friesreliefs vom Artemision in Magnesia. Geordnet nach der Zeit ihrer Auffindung,” Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, archive signature Mag 8, p. 31, no. 28a.

• Fig. 24: Fragment of the Artemision’s southern frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann?, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, verso, 28.6 x 21.7 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. FA-Mag07-0005.

• Fig. 25: Brunnenhaus at the Agora, Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, verso, 28.5 x 21.7 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. FA-Mag09-0002.

• Fig. 26: Germantown (PA), entrances in Main Street, Frank Cousins, c.1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, left: 23.6 x 13.3 cm (photo), center: 23.7 x 13.9 cm (photo), right: 23.7 x 15.5 cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

• Fig. 27: Inscribed parts from cardboard mounts: sculpture, 19th century, Paris, Kassel, Washington, undated, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek.

• Fig. 29: Salem (MA), Frank Cousins’ Garden, Frank Cousins (?), c. 1900, silver gelatin paper on cardboard mount, above: 17.5 x 24 cm (photo), below: 14.7 x 23.6 cm (photo), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, inv.no.1913, 610.

• Fig. 30: New classification of the “Image Archive,” 1960s, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek.

• Fig. 31: Installation shot of the exhibition A New View with framed photographs of Frank Cousins, digital photograph, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, photo: Ludger Derenthal, 2010.

• Fig. 33: Fragment of the Artemision’s northern frieze from Magnesia on the Maeander river, Carl Humann, 1891, albumen paper on cardboard mount, 19.7 x 11.9 cm (photo), 28.6 x 21.7 cm (cardboard), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, inv. no. FA-Mag06-0043, neg. no. PM 1438.

• Fig. 35: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, index card with photographs from former record sheets, Heinz Julius Niehoff, silver gelatin paper, left: 5.8 x 12.3 cm (photo), right: 6.6 x 11.8 cm(photo), 29.8 x 21.1 cm (cardboard, open), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Archiv der Landesstelle für Berlin-Brandenburgische Volkskunde, B.I.2.4.14.-3, “Feste um Pfingsten,” scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.

• Fig. 36: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, index card with photographs and description from former record sheets, Heinz Julius Niehoff, silver gelatin paper, 7.7 x 12.8 cm (photo), 29.8 x 21.1 cm (cardboard, open), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, Archiv der Landesstelle für Berlin-Brandenburgische Volkskunde, B.I.2.4.14.-3, “Feste um Pfingsten,” scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2016.

• Fig. 38: Ochsenfest 1933, Rotha, sequence of film no. 02/007, Heinz Julius Niehoff, Agfa b/w film/reversed digital scan, 3.5 x 16.5 cm, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Institut für Europäische Ethnologie, scan: Wiebke Zeil, 2017.