12.1 Cataloguing the Universe – (Re-)creating the Universe: Arrangement of Conceptual Lists and Their Items in Indo-Iranian Ritual/Magic Poetry

0. Since the beginning of the last century, researchers of oral literature

0.1. The interest in this subject started in Near Eastern studies, due to the abundance of lists and catalogues

0.2. Comparative and contrastive studies of the literary genre of catalogues

0.3. My specific research interest concerns the comparative Indo-Iranian

A. Semantic features of list items, e.g.:

1. ‘Cosmo-logical’ lists.

2. ‘Anthropo-logical,’ esp. ‘physio-logical’/‘somato-graphical’ lists.

3. ‘Glotto-logical’ lists.

4. ‘Numero/arithmo-logical’ lists.

5. ‘Socio-logical’ lists.

6. ‘Chrono-logical’ lists.

7. ‘Topo-logical’ lists.

8. ‘Axio-logical’ lists.

9. ‘Genea-logical’ lists.

10. Akolouthiai: Lists of routines and (ritual[ized]

11. ‘Theo-logical’ lists.

12. Complex structures.

B. Structural features of lists, e.g.:

Intradependency (within list):

(α.) Dimensionality: linear vs. non-linear structures.

(β.) Coordination and subordination of items: head-initial, head-final, multi-

headed list(s) etc.

(γ.) Order of items and directionality within list(s).

(δ.) Correlativity of items within list(s).

(ε.) Variability of items within list(s).

(ς.) Cyclicity vs. openness of list(s).

Interdependency (between lists):

(ζ.) Repetitiveness and recursivity.

(η.) Hierarchy between lists, within ‘super-list(s)’

(θ.) ‘Meta-lists of/about lists.’

The first table (A.) summarizes aspects of the semantic variety of list contents: Here we find ‘cosmo-logical’ lists including items of the macro-cosm, and lists of anthropo-logically relevant elements, of the (human) micro-cosm: e.g. the ones concerning the physio-logical sphere or mapping of the human body

12.2 Structure of Poetic/Magic Lists and Their Contents: Internal and External References

1. If we go directly to the material, in both branches of Indo-Iranian

1.1. A common Old Indo-Iranian

(1a) sahasrākṣaṃ śatadhāraṃ

(1b) r̥ṣibhiḥ pavanaṃ kr̥tam |

(1c) tenā sahasradhāreṇa

(1d) pavamānaḥ punātu mā ||

(2a) yena pūtamantarikṣaṃ

(2b) yasminvāyuradhi śritaḥ | […]

(3a) yena pūtedyāvāpr̥thivī

(3b)āpaḥpūtā athosuvaḥ| […]

(4a) yena pūteahorātre

(4b)diśaḥpūtā uta yenapradeśāḥ| […]

(5a) yena pūtausūryācandramasau

(5b)nakṣatrāṇi bhūtakr̥taḥ[…]

(6a) yena pūtāvedir agniḥ

(6b)paridhayaḥ[…]

(7a) yena pūtaṃbarhir ājyamathohaviḥ| […]

(8a) yena pūtoyajño vaṣaṭkārautāhutiḥ| […]

(9a) yena pūtauvrīhiyavau

(9b) yābhyāṃyajñoadhinirmitaḥ |

(10a) yena pūtāaśvā gāvo

(10b) atho pūtāajāvayaḥ|

(10c) tenā sahasradhāreṇa

(10d) pavamānaḥ punātu mā ||

1. Of (a) thousand eyes, of (a) hundred streams

the purification(has been) made by the seers;

by means of this one of (a) thousand streams

let (Soma,) the one who purifies himself, purify me.

2. By which Intermediate Space (is/has been) purified

on which Wind dwells […].

3. By which (both,) Heaven-and-Earth (have been) purified,

Waters (have been) purified, also Sun […].

soll mich der sich Läuternde (S. Pavamāna) läutern

4. By which (both,) Day-and-Night (have been) purified,

Heavenly Regions (have been) purified and by which Earthly Regions […]

soll mich der sich Läuternde (S. Pavamāna) läutern;

5. By which (both), Sun-and-Moon (have been) purified,

Nakṣatra-s, Bhūtakr̥t-s […].

6. By which the Vedi, the Fire(-Altar) (have been) purified,

the Paridhi-s […].

7. By which the Barhiṣ, the Ājya(-oblation), the Haviṣ(-oblation) (has [= have] been) purified […].

8. By which Sacrifice/Ritual, the Vaṣaṭ-exclamation, and Libation (has [= have] been) purified […].

9. By which (both), Rice-and-Barley (have been) purified,

by both of which Sacrifice/Ritual has been ‘measured into shape’/fixed […].

10. By which horses, cows (have been) purified,

also goats-and-sheep (have been) purified,

by means of this one of (a) thousand streams

let (Soma,) the one who purifies himself, purify me.

1.1.1. The list structure is (stereo)typical. The main predication is constant (‘X is purified’), the formulaic context is repeated in each stanza—while only specific items change, forming simple list(s) with one variable or a group of variables. The list exhibits internal correspondence in a unidimensional, here ‘vertical,’ way, between the varying (groups of) items; this can be summarized by the scheme:

‘Y (is) X […]; by which A & B are Y-ed / by which C & D are Y-ed / by which E & F are Y-ed …, let the Y-ing-oneself Y me.’

1.1.2. The list contains the most important cosmological elements—mostly presented in [natural] pairs

It starts with nature deities and their domains, such as the Intermediate Space (antarikṣa-) with the Wind (vāyu-, stanza 2, verses ab), the ‘Heaven-and-Earth’ (dyāvā-pr̥thivī, stanza 3a), the Waters (āpaḥ), the Sun[light] (súvàr, both 3b) and the Day-and-Night (aho-rātre, 4a).

Then, the list evokes further structures of the macrocosm: the regions of heaven and of earth (4b), cellular bodies / divinities: the Sun-and-Moon (sūryā-candramasau, 5a), Asterisms: nakṣatras and bhūtakr̥ts (both 5b);22

They are followed by basic components of Vedic ritual

the central sacrificial plants

The elements of the list are arranged:

partly in accord with the increasing length of the sound complex (Behaghel’s law)—cf. e.g. in § 1.1.3. below (bahv-)ajāviká- (2-syllabic aja- + 3-syllabic avika-), (bahu-)dāsa-pūruṣá- (2-syllabic dāsa- + 3-syllabic pū̆ruṣa-),

partly in decreasing gradations (anticlimax): e.g. from horse

1.1.3. The same groups of concepts of the triad macro-cosm–ritual

TB. 3,8,5,2–3: […] hótā /

paścā́t prā́ṅ tíṣṭhan prókṣati /

anénā́śvena médhyeneṣṭvā́ /

ayáṁ rā́jāsyái viśáḥ//

bahugváibahvaśvā́yaibahvajāvikā́yai/

bahuvrīhiyavā́yaibahumāṣatilā́yai/

bahuhiraṇyā́yaibahuhastíkāyai/

bahudāsapūruṣā́yairayimátyaipúṣṭimatyai /

bahurāyaspoṣā́yairā́jāstv íti/

[...] the Hotar sprinkles [the horse] standing on the West [facing] to the East with these words: ‘By means of the sacrifice “with” / of this horse (= after/while one sacrifices this horse), which is fit for sacrifice, may this (king) be (the) king of this settlement, which has

manycows, manyhorses, manygoats-and-sheep,

muchrice-and-barley,

muchbeans-and-sesame,

muchgold, manyelephants,

manyslaves-and-servants,

which haswealth, which hasprosperity,

which has muchwealth-and-prosperity.’

1.2. This form of ritual

[…] kuθanmānəmyaoždaθāni

kuθaātrəmkuθaāpəm

kuθaząmkuθagąmkuθauruuarąm

kuθanarəm aṣ̌auuanəmkuθanāirikąm aṣ̌aonīm

kuθastrə̄škuθamā̊ŋhəm

kuθahuuarəkuθaanaγra raocā̊

kuθavīspa vohu mazdaδāta aṣ̌aciθra

āat̰ mraot̰ ahurō mazdā̊:

yaoždāθrəm srāuuaiiōiš zaraθuštra

yaoždāta pascaēta bunnmāna

yaoždātaātrəmyaoždātaāpəm

yaoždātaząmyaoždātagąmyaoždātauruuarąm

yaoždātanarəm aṣ̌auuanəmyaoždātanāirikąm aṣ̌aonīm

yaoždātastrə̄šyaoždātamā̊ŋhəm

yaoždātahuuarəyaoždātaanaγra raocā̊

yaoždātavīspa vohu mazdaδāta aṣ̌aciθra

‘[…] How shall I purify the house,

how the Fire, how the Water,

how the Earth, how the Cow, how the Plant,

how the aṣ̌a-ous Man, how the aṣ̌a-ous Woman,

how the Stars, how the Moon,

how the Sun, how the beginningless Lights

how all the Good, the Mazdā-created, the aṣ̌a-originated?’

Thus spake Ahura Mazdā:

‘You should let the purification(formulae) be heard, Zaraθuštra ,

then the houses will become purified,

the Fire (will become) purified, purified the Water,

purified the Earth, purified the Cow, purified the Plant,

purified the aṣ̌a-ous Man, purified the aṣ̌a-ous Woman,

purified the Stars, purified the Moon,

purified the Sun, purified the beginningless Lights

purified all the Good, the Mazdā-created, the aṣ̌a-originated.’

Furthermore, in a rain spell + purification

1.3. In such ritual

1.3.1.1. The structure of the simple list type is similar to the one in § 1.1.1., with one variable or a group of variables. Scheme: ABCDEXF / ABCDEYF / ABCDEZF … (the variables being set in italics).

One of the most important sorts of simple lists in mantras of the Yajurveda and Atharvaveda

ójo ’asiy ójo me dāḥ svā́hā /1//

sáho ’asi sáho me dāḥ svā́hā //2//

bálam asi bálaṃ me dāḥ svā́hā //3//

ā́yur asiy ā́yur me dāḥ svā́ha //4//

śrótram asi śrótraṃ me dāḥ svā́ha //5//

cákṣur asi cákṣur me dāḥ svā́ha //6//

paripā́ṇam asi paripā́ṇaṃ me dāḥ svā́ha //7//

1. Force art thou; force mayest thou give me: hail!

2. Power art thou; power mayest thou give me: hail!

3. Strength art thou; strength mayest thou give me: hail!

4. Life-time art thou; life-time mayest thou give me: hail!

5. Hearing art thou; hearing mayest thou give me: hail!

6. Sight art thou; sight mayest thou give me: hail!

7. Protection art thou; protection mayest thou give me: hail!

(Whitney and Lanman 1905, vol. 1, 61)

1.3.1.2. An expanded variant of the scheme shows one main variable consisting of items grouped pairwise. This form is more complex than the one in § 1.1.1 (Scheme: ABCDEF(±G) / ABCDEF'(±G') / ABCDEH(±I) / ABCDEH'(±I')…, the variables being set in underlined italics), with regard to the categories of items and includes concepts of cosmo-, theo- and socio-logical significance. The constants in this catalogue of abilities (the nomina praedicati: force; power; strength; heroism; manliness) form a pentadic group and are largely identical with the variables of the last example AVŚ 2,17 in § 1.3.1.1.!

This format appears in magic

‘Indra’s force are you; Indra’s power are you; Indra’s strength are you; Indra’s heroism are you; Indra’s manliness are you; with X-junctions I join you.’

In this sequence of elements—a typical Indo-Iranian

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāya brahmayogaír vo yunajmi //1// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … with K I join you. |

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāya kṣatrayogaír vo yunajmi //2// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … with L I join you. |

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāy endrayogáir vo yunajmi //3// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … with M I join you. |

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāya somayogaír vo yunajmi //4// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … with N I join you. |

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāy āpsuyogáir vo yunajmi //5// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … with O I join you. |

| índrasya- -ója stha- -índrasya sáha stha- -índrasya bálaṃ stha- -índrasya vīryà1ṃ stha- -índrasya nr̥mṇáṃ stha / jiṣṇáve yógāya víśvāni mā bhūtā́ny úpa tiṣṭhantu yuktā́ ma āpa stha //6// |

U = X’s A, U = X’s B, U = X’s C, U = X’s D, U = X’s E … let all P wait upon me; joined to me are you, Q. |

1. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye; Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction (yoga-) with brahman-junctions I join you.

2. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye;

Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction, with kṣatra-junctions I join you.

3. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye;

Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction, with indra-junctions I join you.

4. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye;

Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction, with soma-junctions I join you.

5. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye;

Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction, with water-junctions I join you.

6. Indra’s force are ye; Indra’s power are ye;

Indra’s strength are ye; Indra’s heroism are ye;

Indra’s manliness are ye;

unto a conquering junction; let all existences wait upon (upa-sthā) me; joined to me are ye, O waters.24

1.3.2. Intra-textual correlation: More complex list types exhibit item variation not simply of one variable element (group)—like in § 1.1.[1.] and § 1.3.1.—but of at least two variable item groups per list with internal correlation both between the individual variables A and a within each formula (‘horizontally,’ § 1.3.2.1.)—scheme: AXYZaXYZ—and between the variables (A, B, C, D, E…, a, b, c, d, e) of the different formulae within the list, on the ‘vertical’ axis: Scheme: AXYZaX'YZ / BXYZbX'YZ / CXYZcX'YZ… (§ 1.3.2.2.). In the list structure, the predication, again, is constant, the formulaic context is repeated—specific items vary, forming this time complex list(s) with both internal correspondence and correlation between at least two variable groups of items within one textual unit (hymn, incantation)—i.e. intra-textual correlation.

1.3.2.1. Thus, in the hymn AVP. 7,14 the magic

‘A is full of life: he is full of life due to a. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life’—

e.g. AVP 7,14,1: agnir āyuṣmān ′ sa vanaspatibhir āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ‘Agni/Fire is full of life: he is full of life (by means) of/with/due to the trees/lords of the forest. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.’

1.3.2.2. On the vertical axis, within the list AVP. 7,14 we find a first paṅkti- (pentadic group) of internally correlating items in stanzas 1–5. It includes five nature deities, which take the position of the first variable element (A, B, C, D, E): Fire, Wind, Sun, Moona, b, c, d, e) contains the natural environments of these natural deities: trees for the Fire, space for the Wind, sky for the Sun… In the middle (stanza 6) we find the deified RitualA is X; he is X due to a; being X, let him make me X. B is X; he is X due to b; being X, let him make me X.’

Agni/Fire is full of life (or: life-giving, vivificans): he is full of life by (means of)/with/due to the lords of the wood (the trees). (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

Vāyu/Wind is full of life: he is full of life by/with the intermediate space. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

Sūrya/Sun is full of life: he is full of life by/with the sky. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

Candra/Moon is full of life: he is full of life by/with the asterisms. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

Soma

Yajña/Sacrifice (Ritual

The Confluence (Indus/Ocean?) is full of life: he is full of life by/with the rivers. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

Brahman / the formula(tion) is full of life: it is full of life by/with the brahmacārins. (So,) full of life, let it make me full of life.

Indra is full of life: he is full of life by/with the potency. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

The (All-)Gods are full of life: they are full of life by/with the amr̥ta-. (So,) full of life, let them make me full of life.

Prajāpati / The Lord of (Pro-)Creation is full of life: he is full of life by/with the (pro)creations/progenies/descendants. (So,) full of life, let him make me full of life.

| AVP. 7,14 (ed. Griffiths 2009, ad loc.; transl. partly modified): | Scheme: |

| agnir āyuṣmān ′ sa vanaspatibhir āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||1|| |

A is X; he is X due to a; as X, let him make me X. |

| vāyur āyuṣmān ′ so 'ntarikṣeṇāyuṣmān sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||2|| |

B is X; he is X due to b; as X, let him make me X. |

| sūrya āyuṣmān ′ sa divāyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||3|| |

C is X; he is X due to c; as X, let him make me X. |

| candra āyuṣmān ′ sa nakṣatrair āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||4|| |

D is X; he is X due to d; as X, let him make me X. |

| soma sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||5|| |

E is X; he is X due to e; as X, let him make me X. |

| yajña āyuṣmān ′ sa dakṣiṇābhir āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||6|| |

F is X; he is X due to f; as X, let him make me X. |

| samudra āyuṣmān ′ sa nadībhir āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||7|| |

G is X; he is X due to g; as X, let him make me X. |

| brahmāyuṣmat ′ tad brahmacāribhir āyuṣmat | tan māyuṣmad āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||8|| |

H is X; it is X due to h; as X, let it make me X. |

| indra āyuṣmān ′ sa vīryeṇāyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||9|| |

I is X; he is X due to i; as X, let him make me X. |

| devā āyuṣmantas ′ te 'mr̥tenāyuṣmantaḥ | te māyuṣmanta āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇvantu ||10|| |

J is X; he is X due to j; as X, let them make me X. |

| prajāpatir āyuṣmān ′ sa prajābhir āyuṣmān | sa māyuṣmān āyuṣmantaṃ kr̥ṇotu ||11|| |

K is X; he is X due to k; as X, let him make me X. |

1.3.2.3. In the same way, we find double-list structures with parallelism of two variables—again, in purification

‘You should purify A (in exchange) for a, B (in exchange) for b, C (in exchange) for c.’

Here, the variable element X represents persons of high social circles in decreasing enumeration / gradation: a priestB), a ‘clan-lord of a clan’ (C), a ‘settlement-lord of a settlement’ (D) a ‘house-lord of a house’ (E)—a sequence containing a stylistically marked, continuous paronomastic structure with etymological relation between its elements (cf. Sadovski 2006, 531–535). The variable element Y comprises the dakṣiṇas for purification

| Vd. 9,37: āθrauuanəm yaoždaθō | Purify an A |

| dahmaiiāt̰ parō āfritōit̰ | for an a (in exchange). |

daiŋ́hə̄uš daiŋ́hu.paitīm yaoždaθō |

Purify a B-lord of B |

| uštrahe paiti aršnō aγriiehe | for a b [male] top-animal. |

zaṇtə̄uš zaṇtu.paitīm yaoždaθō |

Purify a C-lord of C |

| aspahe paiti aršnō aγriiehe | for a c [male] top-animal. |

vīsō vīspaitīm yaoždaθō |

Purify a D-lord of D |

| gə̄uš paiti uxšnō aγriiehe | for a d [male] animal. |

nmānahe nmānō.paitīm yaoždaθō |

Purify a E-lord of E |

| gə̄uš paiti aziiā̊ | for an e [fem.] animal. |

You should purify a priest

for a dahma-ful blessing;

you should purify acountry-lord of a country

for / against a male camel of top/extreme (value);

you should purify aclan-lord of a clan

for / against a horse, a stallion (a “horse-stallion”) of extreme (value); you should purify a settlement-lord of a settlement

for / against a [male] cow, a bull (a “cow-bull”) of extreme (value);

you should purify ahouse-lord of a house

for / against a cow, a fertile cow.

1.3.2.3.1. For the figure ‘settlement-lord of a settlement,’ Avestanvīsō vīspaiti, we can find good parallels in Vedic, RV. 9,108,10b viś-páti- viśā́m—cf. also ‘cow

1.3.2.3.2. In cases like Yt. 13,150, we find the same IIr. ‘hierarchy of social structures,’ this time in increasing enumeration (gradation): house (E)—settlement (D)—clan (C)—country (B; the symbol letters here correspond to the ones of the first list in § 1.3.1.). The variables here concern chrono-logical dimensions: past, future, present:

| paoiriiąn t̰kaēšə̄ yazamaide | We worship X |

nmānanąmca vīsąmca |

of E and of D |

zaṇtunąmca dax́iiunąmca |

and of C and of B |

| yōi ā̊ŋharə: | who [BE-past]. |

| paoiriiąn t̰kaēšə̄ yazamaide | We worship X |

nmānanąmca vīsąmca |

of E and of D |

zaṇtunąmca dax́iiunąmca |

and of C and of B |

| yōi bābuuarə: | who [BE-prospective] |

| paoiriiąn t̰kaēšə̄ yazamaide | We worship X |

nmānanąmca vīsąmca |

of E and of D |

zaṇtunąmca dax́iiunąmca |

and of C and of B |

| yōi həṇti. | who [BE-present]. |

We worship the first teachers

of thehousesand of thesettlements

and of theclansand of thecountries

which were / have been (there).

We worship the first teachers

of thehousesand of thesettlements

and of theclansand of thecountries

which will be (there).

We worship the first teachers

of thehousesand of thesettlements

and of theclansand of thecountries

which are ([being] there).

1.3.3. Inter-textual correlation: Still more complex list types include correlations between varying lists—not only within one textual unit (hymn, incantation)—like in § 1.3.2.[2.] and § 1.3.3.1 (Scheme: AXYZaX'YZ / BXYZbX'YZ / CXYZcX'YZ…)—but also between several textual units (§ 1.3.3.2.). Once more, yet again, the predication is constant, the context is repeated: specific items vary, forming complex list(s) with both internal correspondence and correlation between at least two variable groups of items—in this case, however, not only with intra-textual but also with inter-textual correlation of lists:

1.3.3.1. The basic component here is an intra-textually correlative list (consisting, for its part, of sub-elements of simpler shape, as described in § 1.3.2.1.). In the hymn AVŚ. 2,19, for instance, the structure is: X, Anoun AverbY / X, Bnoun BverbY / X, Cnoun CverbY …—items varying and internally correlated within the list, from stanza to stanza. The pentadic listheat is, heat by/with it [our hater]; what your flame is, flame by it; what your beam(ray)/gleam/glare is, beam/gleam/glare by it.’ So, the intra-textual variation goes on through five stanzas, in which the deity addressed by listing its main attributes (essentially correlated with one another) is constantly the Fire-god

| Invoc. | Mantra: ‘O, X (= Fire), what your ABCDEnoun is, do ABCDEverb it against that one who hates us, whom we hate’. |

| AVŚ. | 2,19: | ||

| ágne | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Agni, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Agni, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te 'rcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Agni, | what your beam (ray) is, beam by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Agni, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Agni, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it […]. |

1.3.3.2. However, this list itself is part of a complex ‘list of lists’: In Atharvaveda

| Invoc. | Mantra: O, XYZVW (= Fire, Wind, Sun…), what your ABCDEnoun is, do ABCDEverb it against that one who hates us, whom we hate! |

| AVŚ. | 2,19: | ||

| ágne | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Agni, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Agni, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te 'rcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Agni, | what your beam is, beam by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Agni, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y […] |

| ágne | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Agni, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it. |

| AVŚ. | 2,20: | ||

| vā́yo | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Vāyu, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y […] |

| vā́yo | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Vāyu, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y […] |

| vā́yo | yát te 'rcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Vāyu, | what your beam is, beam by it against Y […] |

| vā́yo | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Vāyu, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y […] |

| vā́yo | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Vāyu, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it […] |

| AVŚ. | 2,21: | ||

| sū́rya | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Sūrya, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y […] |

| sū́rya | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Sūrya, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y […] |

| sū́rya | yát te 'rcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Sūrya, | what your beam is, beam by it against Y […] |

| sū́rya | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Sūrya, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y […] |

| sū́rya | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Sūrya, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it […] |

| AVŚ. | 2,22: | ||

| cándra | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Candra, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y […] |

| cándra | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Candra, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y […] |

| cándra | yát te 'rcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Candra, | what your beam is, beam by it against Y |

| cándra | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Candra, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y […] |

| cándra | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Candra, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it […] |

| AVŚ. | 2,23: | ||

| ā́po | yád vas tápas téna táṃ práti tapata yò ’asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||1|| |

Waters, | what your heat is, heat by it against Y [...] |

| ā́po | yád vo háras téna táṃ práti harata yò ’asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||2|| |

Waters, | what your flame is, flame by it against Y [...] |

| ā́po | yád vo ’arcís téna táṃ prátiy arcata yò ’asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||3|| |

Waters, | what your beam (ray) is, beam by it against Y [...] |

| ā́po | yád vaḥ śocís téna táṃ práti śocata yò ’asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||4|| |

Waters, | what your gleam is, gleam by it against Y [...] |

| ā́po | yád vas téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇuta yò ’asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ ||5|| |

Waters, | what your glare/splendour is, make/render Y splendourless by it [...]. |

Represented as a summarized list structure:

| AVŚ. 2,19: | AVŚ. 2,20: | AVŚ. 2,21: | AVŚ. 2,22: | AVŚ. 2,23: |

| ágne + Mantra |

vā́yo + Mantra |

sū́rya + Mantra |

cándra + Mantra |

ā́po + Mantra [Pl.] |

| A./Fire (5 items) |

V./Wind (5 items) |

S./Sun (5 items) |

C./Moon (5 items) |

Äp./Waters (5 items) |

1.3.3.3. As a result, we have a multi-dimensional list, with both “horizontal” and “vertical” relations within and beyond the individual list(s): the ultimate form of stereometric, multi-dimensional representation of the Universe.

| 2,19 | 2,20 | 2,21 | 2,22 | 2,23 | → Complex list ↓ |

| Invoc. | Invoc. | Invoc. | Invoc. | Invoc. | Mantra: ‘what your X is, do X' with it against that one who hates us, whom we hate’ |

| ágne | vā́yo | sū́rya | cándra | ā́po | yát te tápas téna táṃ práti tapa yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ |1| |

| ágne | vā́yo | sū́rya | cándra | ā́po | yát te háras téna táṃ práti hara yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ |2| |

| ágne | vā́yo | sū́rya | cándra | ā́po | yát te 'arcís téna táṃ prátiy arca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ |3| |

| ágne | vā́yo | sū́rya | cándra | ā́po | yát te śocís téna táṃ práti śoca yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ |4| |

| ágne | vā́yo | sū́rya | cándra | ā́po | yát te téjas téna tám atejásaṃ kr̥ṇu yò 'asmā́n dvéṣṭi yáṃ vayáṃ dviṣmáḥ |5| |

In the Avesta

1.3.3.4. Both Indo-Iranian

The first list (Yt. 3,7–9) contains a general survey of adversaries of Zoroastrianism, of diseases

The second list (Yt. 3,10–13) represents an expanded form that subsumes the same creatures within an appeal to kill ‘thousands and ten thousand times ten thousands’ of them.

The third turn (Yt. 14–16) contains a complex list of the same creatures, in positive and superlative form, within a lament

2. ‘Physio-logia.’ Another genre of catalogues

2.1. In Indo-Iranian

2.1.1. The Avesta

The main formula can be extrapolated from the sequence Vd. 8,41ff., cf. Vd. 8,41–42:

dātarə gaēθanąm astuuaitinąm aṣ̌āum

yezica āpō vaŋuhīš

barəšnūm vaγδanəm pourum paiti.jasaiti

kuua aēšąm

aēša druxš yā nasuš upa.duuąsaiti:

āat̰ mraot̰ ahurō mazdā̊:

paitiša hē hō.nā aṇtarāt̰ naēmāt̰ bruuat̰.biiąm aēšąm

aēša druxš yā nasuš upa.duuąsaiti.

42. dātarə gaēθanąm astuuaitinąm aṣ̌āum

yezica āpō vaŋuhīš

paitiša hē hō.nā aṇtarāt̰ naēmāt̰ bruuat̰.biiąm paiti.jasaiti

kuua aēšąm

aēša druxš yā nasuš upa.duuąsaiti:

āat̰ mraot̰ ahurō mazdā̊:

pasca hē vaγδanəm aēšąm

aēša druxš yā nasuš upa.duuąsaiti.

O Creator of the ‘bony’ / material world, thou Aṣ̌a-ful One!

When the good waters

first arrive to the [body part A, here:] top of the head,

whereon of them [= of persons that have had a contact with a corpse]

does the Druj, the Nasu [the mortiferous epidemy witch/demon], move?

So spoke Ahura Mazdā:

‘Upon the [body part B, here:] inner part between their eyebrows

the Druj, the Nasu, moves.’

42. O Creator of the ‘bony’ material world, thou Aṣ̌a-ful One!

When the good waters

arrive up to the [body part B, here:]

inner part between their eyebrows,

on which place of them

does the Druj, the Nasu, move?

So spoke Ahura Mazdā:

‘Upon the [body part C, here:] backside of their head

the Druj, the Nasu, moves.’

The list has complex, spiral organization. We can call it ‘triple directionality’: the process develops (1) from the upper body part to the lower one, (2) from front to back side, and (3) from right to left, always recursively, step-by-step:

| – Vd. 8,41: | A = top of the head; B = space between the eye-brows |

| – Vd. 8,42: | B = space between the eye-brows; C = backside of the head |

| – Vd. 8,43: […] | C = backside of the head; D = the upper part of the face, etc. […] |

| – Vd. 8,62: | P = right knee; Q = left knee |

| – Vd. 8,63: | Q = left knee; R = right shin |

| – Vd. 8,64: | R = right shin; S = left shin |

| – Vd. 8,65: | S = left shin; T = right ankle |

| – Vd. 8,66: | T = right ankle; U = left ankle |

| – Vd. 8,67: | U = left ankle; V = right fore-foot |

| – Vd. 8,68: | V = right fore-foot/instep; W = left fore-foot/instep |

| – Vd. 8,69: | W = left fore-foot; X = under the sole of the foot |

| – Vd. 8,70: | X = right sole; Y = left sole |

| – Vd. 8,71: | Y = left sole; Z = Ø, i.e.: the Druj Nasu disappears |

At the end of the sequence, at the left sole, the witch

2.1.2. Vedic purification

2.1.2.1. Lists with body-part groupings (and often with easily comprehensible classificatory organization) are represented by Vedic hymns

akṣī́bhyāṃ te nā́sikābhyāṃ

kárṇābhyāṃ chúbukād ádhi |

yákṣmaṃ śīrṣaṇyàṃ mastíṣkāj

jihvā́yā ví vr̥hāmi te ||1||

grīvā́bhyas ta uṣṇíhābhyaḥ

kī́kasābhyo anūkíyā̀t |

yákṣmaṃ doṣaṇyàm áṃsābhyāṃ

bāhúbhyāṃ ví vr̥hāmi te ||2||

hŕ̥dayāt te pári klomnó

hálīkṣṇāt pārśuvā́bhiyām |

yákṣmaṃ mátasnābhyāṃ plīhnó

yaknás te ví vr̥hāmasi ||3||

āntrébhyas te gúdābhiyo

vaniṣṭhór udárād ádhi |

yákṣmaṃ kukṣíbhiyām plāśér

nā́bhiyā ví vr̥hāmi te ||4||

ūrúbhyāṃ te aṣṭhīvádbhyāṃ

pā́rṣṇibhyāṃ prápadābhiyām |

yákṣmaṃ bhasadyàṃ śróṇibhyāṃ

bhā́sadaṃ bháṃsaso ví vr̥hāmi te ||5||

asthíbhyas te majjábhiyaḥ

snā́vabhyo dhamánibhiyaḥ |

yákṣmam pāṇíbhyām aṅgúlibhyo

nakhébhyo ví vr̥hāmi te ||6||

áṅge-aṅge lómni-lomni

yás te párvaṇi-parvaṇi |

yákṣmaṃ tvacasyàṃ te vayáṃ

kaśyápasya vībarhéṇa

víṣvañcaṃ ví vr̥hāmasi ||7||

1. From27 your eyes, from [your] nostrils,

from [your] ears, from [your] chin,

from [your] brain, from [your] tongue,

I tear away for you the yákṣma who is in the head.

2. From your neck, from the nape of [your] neck,

from [your] vertebrae, from [your] spine,

from [your] shoulders, from [your] forearms,

I tear away for you the yákṣma who is in the arm.

3. From your heart, from [your] lungs,

from [your] hálīksṇa, from [your] two sides,

from [your] two mátasnas, from [your] spleen,

from [your] liver, we tear away for you the yákṣma.

4. From your bowels, from [your] intestines,

from [your] rectum, from [your] stomach,

from the lateral parts of [your] abdomen, from [your] plāśi,

from [your] navel, I tear away for you the yákṣma.

5. From your thighs, from [your] kneecaps,

from [your] heels, from the front of [your] feet,

from [your] haunches, from [your] bháṃsas,

I tear away for you the yákṣma who is in the backside.

6. From your bones, from [your] marrows,

from [your] tendons, from [your] (blood) vessels,

from [your] hands, from [your] fingers,

from [your] nails, I tear away for you the yákṣma.

7. By means of Kaśyapa’s exorcising spell,

we tear completely away

the yákṣma who is of your skin,

who is in your every limb,

every hair [and] every joint.

2.1.2.2. In the magic

áṅgād-áṅgāl lómno-lomno

jātám párvaṇi-parvaṇi /

yákṣmaṃsárvasmād ātmánas

tám idáṃ ví vr̥hāmi te //

From each limb, from each hair,

the emaciation born/arisen in each joint,

from thewhole (body) trunk,

this one I pull off from you now/here.

2.1.3. As is well known, we have to do with a common Indo-European topos of healing lists. Parallels in Germanic, related not only typologically but also genealogically to the Indian ones, have been described at the dawn of comparative Indo-European philology by Adalbert Kuhn.28 They occur in the famous Merseburger Zaubersprüche, constantly re-edited and re-assessed ever since the mid-nineteenth century—most recently in the proceedings volume29 of a colloquium in Halle 2000:

Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods, when Balder’s foal sprained his foot. Bechanted it Sinhtgunt, (and) the Sun her sister; bechanted it Friya, (and) Volla her sister; bechanted it Wodan as best he could. Like bone-sprain, like blood-sprain, like joint-sprain: bone to bone, blood to blood, joint to joint: so be they glued.30

Cf. Mantras from the Atharvaveda

yát te riṣṭáṃ yát te dyuttám

ásti péṣṭraṃ ta ātmáni /

dhātā́ tád bhadráyā púnaḥ

sáṃ dadhat páruṣā páruḥ //2//

sáṃ te majjā́ majñā́ bhavatu

sám u te páruṣā páruḥ /

sáṃ te māṃsásya vísrastaṃ

sám ásthiy ápi rohatu //3//

majjā́ majñā́ sáṃ dhīyatāṃ

cármaṇā cárma rohatu /

ásr̥k te ásthi rohatu

māṃsáṃ māṃséna rohatu //4//

lóma lómnā sáṃ kalpayā

tvacā́ sáṃ kalpayā tvácam/

ásr̥k te ásthi rohatu

chinnáṃ sáṃ dhehiy oṣadhe //5//

sá út tiṣṭha préhi

prá drava ráthaḥ sucakráḥ /

supavíḥ sunā́bhiḥ

práti tiṣṭha urdhváḥ //6//

2. What of thee is torn, what of thee is broken,

(or what) of thee crushed—

let Dhātar (put) it auspiciously

put that together again, joint with joint.

3. Together be (thy) marrow with marrow,

together (thy) joint with joint;

together thy flesh’s sundered [part],

together let thy bone grow over.

4. Marrow with marrow together be set;

skin with skin let grow;

thy blood, bone let grow,

flesh with flesh let grow.

5. Hair with hair fit (thou) together;

with hide together fit hide;

thy bone with bone let grow;

set the severed together, O herb.

6. So stand up, go forth, run forth,

(as) a chariot well-wheeled,

well-tired, well-naved.

Stand firm upright!31

Cf. also the additional interpretations of the hymn by (Eichner and Nedoma 2000–2001b). — A somewhat divergent, important parallel appears in the new fragments of the Paippalāda—AVP. 4,15,1–4. It has been edited by (Bhattacharya 1997) and re-assessed and commented upon by Griffiths and Lubotsky32 and is, by now, the best preserved parallel to the Germanic formula:

saṃ majjā majjñā bhavatu

sam u te paruṣā paruḥ |

saṃ te rāṣṭrasya visrastaṃ

saṃ snāva sam u parva te ||1||

majjā majjñā saṃ dhīyatām

asthnāsthiy *api rohatu |

snāva te saṃ dadhmaḥ snāvnā

carmaṇā carma rohatu ||2||

loma lomnā saṃ dhīyatāṃ

tvacā saṃ kalpayā tvacam |

asr̥k te asnā rohatu

māṃsaṃ māṃsena rohatu ||3||

rohiṇī saṃrohiṇiy

*asthnaḥ śīrṇasya rohiṇī |

rohiṇyām ahni jātāsi

rohiṇiy asiy oṣadhe ||4||

1. Let marrow come together with marrow,

and your joint together with joint,

together what of your flesh has fallen apart,

together sinew and together your bone.

2. Let marrow be put together with marrow,

let bone grow over [together] with bone.

We put together your sinew with sinew,

let skin grow with skin.

3. Let hair be put together with hair.

[Rohinī-plant (‘Grower’)], fit together skin with skin.

Let your blood grow with blood;

let flesh grow with flesh.

4. Grower [are you], healer,

grower of the broken bone.

You are born on the Rohinī day,

you are grower, o plant.

2.2. Other forms of body part lists include depictions of clothing, regalia

vaēm zaraniiō.xaoδəm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.pusəm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.minəm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.vāṣ̌əm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.caxrəm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.zaēm yazamaide

vaēm zaraniiō.vastrəm yazamaide

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden head decoration,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden diadem,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden necklace,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden chariot,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden wheel,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden weapon,

We worship Vaiiu, the one with the golden robe/‘vestments’.

2.3. Body as list: Under this rubric, we observe the highly interesting metaphoric type characterized, first, by the ritual

2.3.1. I comment on lists in formulae of rites of ritual

2.3.1.1. In Indo-Iranian

ápāñcau ta ubháu bāhū́

ápi nahyāmiy āsíyàm |

agnér devásya manyúnā

téna te ’vadhiṣaṃ havíḥ ||4||

ápi nahyāmi te bāhū́

ápi nahyāmiy āsíyàm |

agnér ghorásya manyúnā

téna te ’vadhiṣaṃ havíḥ ||5||

Turned back/behind are your two arms.

I bind (your) mouth.

With the wrath of god Agni

I destroyed your oblation.

I bind your arms,

I bind (your) mouth.

With the wrath of terrible Agni

I destroyed your oblation.

2.3.1.2. Parallels from other (Indo-European) traditions come from Greek

Side A: (1) I bind down Theagenes, his tongue and his soul and the words he uses;

(2) I also bind down the hands and feet of Pyrrhias, the cook, his tongue, his soul, his words; […]

(8) I also bind down the tongue of Seuthes, his soul, and the words he uses, just like his feet, his hands, his eyes, and his mouth;

(9) I also bind down the tongue of Lamprias, his soul, and the words he uses, just like his feet, his hands, his eyes, and his mouth.

Side B: All these I bind down, I make them disappear, 1 bury them, I nail them down (Graf 1997, 122).

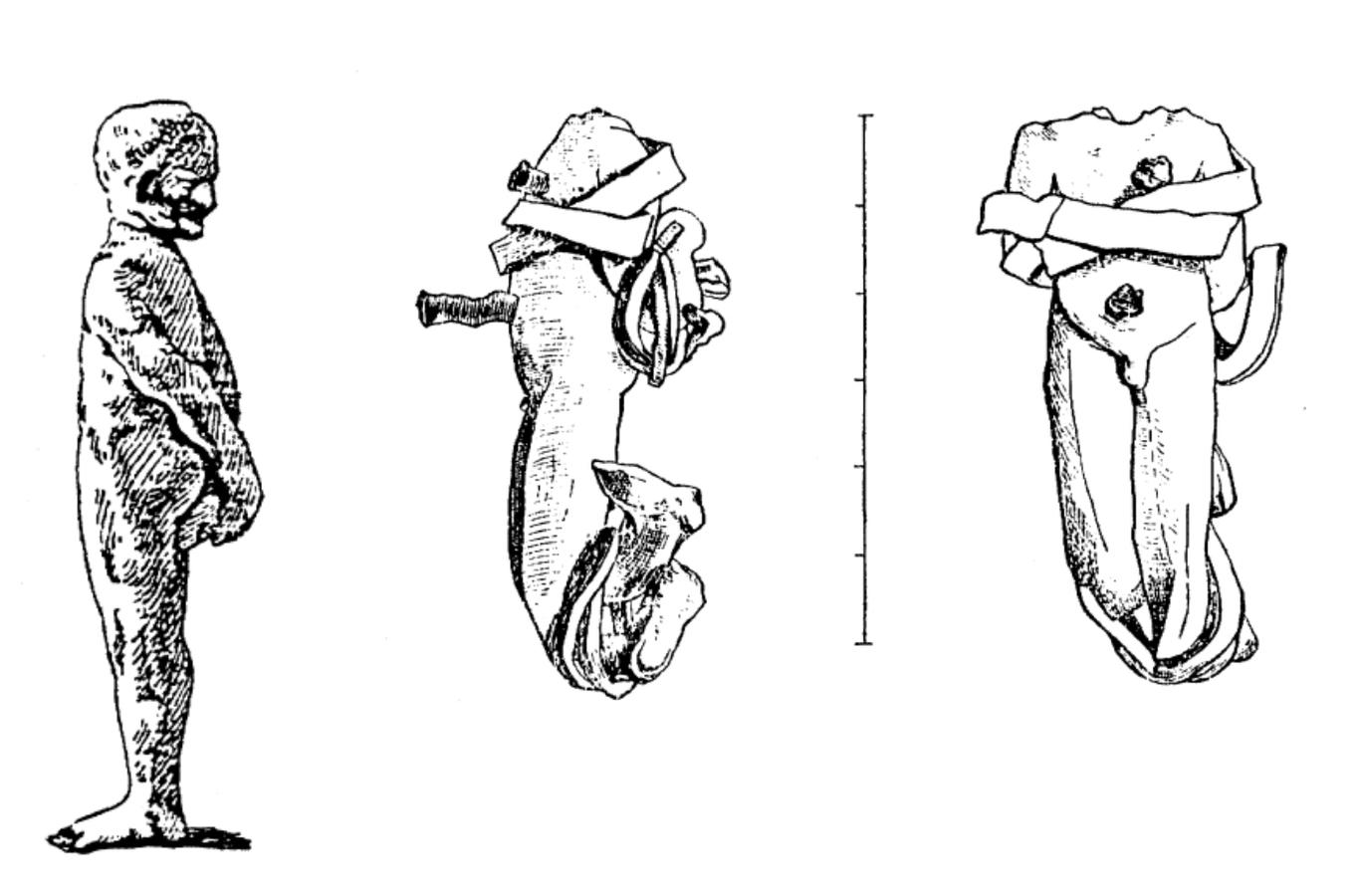

Fig. 12.1: Left side: Lead figurine from Athens, first published in Mélusine 9, 1898–1899, 104, fig. 2. Right side: Decapitated lead figurine from Athens (cf. Faraone 1991, fig. 6–7, 2001), first publ. in Philologus 61, 1902, 37.

On evidence for such practices in Indo-Iranian

2.3.2. Verba concepta—mantras of blessing or curse—can exercise their effect not only when being recited: a further projection of their performative force is achieved by writing sacred syllables of such spells on body parts

Such practices do not concern exclusively the sphere of ‘black magic

3. ‘Glotto-logia’: Among what I subsume under ‘glotto-logical lists,’ there are elaborated sequences of language items and metalinguistic analogies. It is about ‘linguistic mannerisms’ on various levels of poetical language—plays with objective language items, ana-logiae, meta-linguistic issues and idiolectal, nonce formations used by the poets on a range scale between glosso-lalein33 and ‘glosso-logein.’

3.1. Syntaxis: To start with higher levels of rhetoric

3.1.1. In case of variation of nominal case-forms with different case desinences, classical rhetoric theory speaks of a polyptoton

• TS 4,5,1–2:

yā́ ta íṣuḥ śivátamā

śivám babhū́va te dhánuḥ /

śivā́ śaravyā̀ yā́ táva

táyā no rudra mr̥ḍaya // (b)

yā́ te rudra śivā́ tanū́r

ághorā́pāpakāśinī / // (c) […]

śivā́ṃ giritra tā́ṃ kuru […] (d)

śivena vácasā tuvā

gíriśā́chā vadāmasi / […] // (e)

That arrow of thine which (is) the most gracious/propitious,

what is thy propitious bow,

what (is) thy propitious arrow(-missile),

with this (one), Rudra, be thou mild/merciful to us. […]

That body of thine, Rudra, which is propitious,

not formidable, not of bad/evil look […]

make it, o mountain-guardian, (a) propitious (one) […]

With a propitiatory speech

we speak to you, (o) mountain-dweller […].

• RV. 4,7,11ab:

tr̥ṣú yád ánnā tr̥ṣúṇā vavákṣa

tr̥ṣúṃ dūtáṃ kr̥ṇute yahvó agníḥ /

Wenn er gierig die Speisen (verzehrend) mit der gierigen (Flamme) wächst, so macht der jüngste Agni den gierigen (Wind) zu seinem Boten (Geldner 1951–1957, 1, ad loc.).

Eight variants of four different case-forms of the name of the Fire-god agní- appear at the ‘locus classicus’ RV. 1,1a-5a.6b-7a.9b,34 with identical stem-vowel / case-ending complexes in different morphonological sandhi-forms each—contracted; elided; with or without accent; with -ḥ vs. -r etc.

3.1.2. In the specific case which I will call “pam-ptoton,” we discover a remarkable later mantra listing a complete paradigm of all eight (= 7+1) case forms of Rāma’s name, in order of a nominal paradigm as taught by Pāṇini (+Voc.!):

| Rām.-Mahātmyam 1,1 (cf. Deeg 1995, 59; Liebich 1919, 14f.): | Singular | |

| śrīrāmаḥ śaraṇaṃ samastajagatāṃ, | Nom. | The venerable Rāma [Sing. Nom.] is the refuge of all beings. |

| rāmaṃ vinā kā gatī, | Acc. | Which road/way [is] without Rāma? |

| rāmeṇa pratihanyate kalimalaṃ, | Instr. | By Rāma, the stain of the Kali epoch is averted. |

| rāmāya kāryaṃ namaḥ; | Dat. | It is to Rāma veneration has to be done/offered. |

| rāmāt trasyati kālabhīmabhujago, | Abl. | In front of Rāma, the snake Kālabhīma trembles. |

| rāmasya sarvaṃ vaśe, | Gen. | In Rāma’s power is “(the) all” / entire (universe). |

| rāme bhaktir akhaṇḍitā bhavatu – | Loc. | Let the devotion/dedication to Rāma be uninterrupted, |

| me rāma tvam evāśrayaḥ | – Voc. – | to me, o Rāma, be you support! |

3.2. Morpho-logia: On this level, we find, for example, lists of concepts in all ‘gender’ forms, like the ones in masculine/feminine/neuter, pumaṁs- – strī- – na(strī)puṁsaka-, in the Paippalāda-Saṃhitā:

| AVP. 6,8: | Gender | |

| sahasva yātudhānān | Masc. | Suppress the sorcerers |

| sahasva yātudhāniyaḥ | | Fem. | suppress the sorceresses, |

| sahasva sarvā rakṣāṃsi | Neut. | suppress all demons |

| sahamānāsiy oṣadhe || | Generalization | you are suppressing, ο Plant! |

3.3. And for what regards the ‘Phono-logia magica

Consonants in the first hymn of the RV exhibit statistically significant occurrence frequencies: they seem to be distributed in four classes, according to the features ‘voiced’ vs. ‘voiceless’ and ‘aspirated’ vs. ‘unaspirated,’ in the following way:

| 1 | voiceless unaspirated consonants | k (4), c (3), t (32), p (8), ś (6), ṣ (7), s (20) |

| 2 | voiceless aspirated consonants | ch (1), ḥ (7) |

| 3 | voiced unaspirated consonants | g (13), ṅ (2), j (4), ñ (2), ḍ (2), ṇ (1), d (17), n (21), m (22), y (16), r (25), v (35) |

| 4 | voiced aspirated consonants | dh (5), bh (7), h (4) |

The occurrence frequencies of all the four classes are integral multiples of 8:

Relation between the frequencies of the voiced and voiceless consonants: 176: 88 = 2 : 1.

Relation between the frequencies of the aspirated and unaspirated consonants: 24 : 240 = 1 : 10.

| voiced | voiceless | total sum | [1] voiceless unaspirated consonants | 80 = 10 x 8 | |

| aspirated | 16 | 8 | 24 | [2] voiceless aspirated consonants | 8 = 1 x 8 |

| unaspirated | 160 | 80 | 240 | [3] voiced unaspirated consonants | 160 = 20 x 8 |

| total sum | 176 | 88 | 264 | [4] voiced aspirated consonants | 16 = 2 x 8 |

Similar proportions can be established for vowels, too, according to four specific classes. Also here, the occurrence frequencies of all the four classes are integral multiples of 8.

3.4. Semasio-logia vs. onomasio-logia:

3.4.1. On poetic uses of paronomasia

Specific item(s) remain[s] constant; general context varies and form (complex) list(s)—RV. 5,40,1c-4b, with soma

vŕ̥ṣann indra vŕ̥ṣabhir vr̥trahantama //1//

vŕ̥ṣā grā́vā vŕ̥ṣā mádo

vŕ̥ṣā sómo ayáṃ sutáḥ /

vŕ̥ṣann indra vŕ̥ṣabhir vr̥trahantama//2//

vŕ̥ṣā tvā vŕ̥ṣaṇaṃ huve

vájriñ citrā́bhir ūtíbhiḥ /

vŕ̥ṣann indra vŕ̥ṣabhir vr̥trahantama //3//

r̥jīṣī́ vajrī́ vr̥ṣabhás turāṣā́ṭ

chuṣmī́ rā́jā vr̥trahā́ somapā́vā /

[…] (o) bull Indra, with the bulls, you (great)est Vr̥tra-killer!

2. Bull(-like) is the pressing-stone, bull(-like) the intoxication,

bull(-like) this Soma, (when) pressed-out,

(o) bull Indra, with the bulls, you (great)est Vr̥tra-killer!

3. (As a) bull, I (am) call(ing) you, the bull,

o Vajra-bearer, with (your) wonderful helps/favors,

(o) bull Indra, with the bulls, you (great)est Vr̥tra-killer!

4. Marc-drinking, vajra-bearing, a bull, overcoming the powerful,

a courageous king, a Vr̥tra-killer and soma-drinker […]!

3.4.2. Etymo-logia magica: Beyond the semasio-logical word-plays in 3.4.1, I would like to underline two types of esoteric lists: The first are etymo-logical or pseudo-etymological associations in mantras per analogiam. The magic

3.4.2.1. Explicative ‘etymologisation’ of epithets, for exegetic purposes: Evidence of the relation between so-called ‘semantic etymologies

viṣuvān viṣṇo bhava

tuvaṃ yo nr̥patir mama

O Viṣṇu, be the culminating point (viṣuvánt-),

thou who art my lord. (cf. ed. Griffiths)

or from TS. 1,1,4,1de:

dhū́r asi; dhū́rva táṃ yò ’asmā́n dhū́rvati

táṃ dhūrva yáṃ vayáṃ dhū́rvāmas

Thou art the yoke. Injure him who injures us,

injure him whom we injure.36

as well as in the typical Indo-Iranian

| vanō.vīspā̊ nąma ahmi […] | A-B C D |

| auuat̰ vanō.vīspā̊ nąma ahmi | E A-B C D |

| yat̰ uua dąma vanāmi | F G A' |

| vohuuaršte nąma ahmi […] | H-I C D |

| auuat̰ vohuuaršte nąma ahmi | E H-I C D |

| yat̰ vohū vərəziiāmi | F H I |

I am ‘All-Vanquisher’ by name,

Therefore I am ‘All-Vanquisher’ by name

because I vanquish both creations,

I am ‘Good-Doer / Bene-factor’ by name,

Therefore I am ‘Good-Doer / Bene-factor’ by name

because I do good / bene-fit.

3.4.2.2. Not only verba sacra stand for res sacrae—but also res sacrae occur because of verba sacra: This phenomenon concerns the ‘inverse’ influence of word and sound structures on ritual

amū́n aśvattha níḥ śr̥ṇīhi

khā́dāmū́n khadirājirám |

tājádbháṅga iva bhajantāṃ

hántuv enān vádhako vadháiḥ ||3||

Tear as under those (enemies), o Aśvattha (ficus religiosa)!

devour (khāda) them, o Khadira (acacia catechu)!

Like the Tājadbhaṅga (ricinus communis) they shall be broken (bhaj)!

May the vadhaka-(tree) kill them with (its) weapons (vadha-).

3.4.3. Polysemics can be involved as a device in ritul poetry especially in the case of mystical associations of divergent meanings of a sound complex—cf. the associative play with polysemantic words like suvarṇa—are to be found throughout Indian poetical tradition, also in post-Vedic times, like in the beautiful ‘manneristic’ example of Rāmāyana 5,32,45:

suvarṇasya suvarṇasya

suvarṇasya ca bhāvini /

rāmeṇa prahitaṃ devi

suvarṇasyāṅgurīyakam

Rāma sends you, fair princess, this ring,

made of gold [suvarṇa-], of beautiful colour [suvarṇa-]

and well-engraved [suvarṇa-] letters and weighing a suvarṇa.38

Highlights of other types of catalogues

Bibliography

Alper, H.P. (1989). Understanding Mantras. New York: State University of New York Press.

Bhattacharya, Dipak (1997). Atharvavedīyā Paippalādasaṃhitā: The Paippalāda Saṃhitā of the Atharvaveda. Critically edited from palmleaf manuscripts in the Oriya script discovered by Durgamohan Bhattacharyya and one Śāradā manuscript. Kolkata/Calcutta: Asiatic Society.

Bloomfield, M. (1897). Hymns of the Atharvaveda. Together with Extracts from the Ritual Books and the Commentaries Translated […]. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Braarvig, J.E. (2000). Magic: Reconsidering the Grand Dichotomy. In: The World of Ancient Magic: Papers from the First International Samson Eitrem Seminar at the Norwegian Institute at Athens, 4–8 May 1997, Athens, May 1997 Ed. by D.R. Jordan, H. Montgomery, H. M.. Papers from the Norwegian Institute at Athens 4. Bergen: Norwegian Institute at Athens 21-54

Braarvig, J.E., M.J. Geller, M. G., Sadovski M.J. (2012). Multilingualism and History of Knowledge. Vol. II: Linguistic Developments along the Silkroad: Archaism and Innovation in Tocharian. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- (forthcoming). Lists, Catalogues, and Classification Systems from Comparative and Historical Point of View: Multilingualism and History of Knowledge. Wien.

Braarvig, J.E., M.J. Geller, M. G., V.Sadovski M.J. (2013). Multilingualism and History of Knowledge. Vol. I: Linguistic Developments along the Silkroad: Archaism and Innovation in Tocharian. Wien.

Bronkhorst, J. (2001). Etymology and Magic: Yāska's Nirukta, Plato's Cratylus, and the Riddle of Semantic Etymologies. Numen 48: 147-203

Darmesteter, J. (1892). Le Zend-Avesta. Tome II. Paris: Theologica Books.

Deeg, M. (1995). Die altindische Etymologie nach dem Verständnis Yāska's und seiner Vorgänger: eine Untersuchung über ihre Praktiken, ihre literarische Verbreitung und ihr Verhältnis zur dichterischen Gestaltung und Sprachmagie. Dettelbach: J.H. Röll.

Deichgräber, K. (1965). Die Musen, Nereiden und Okeaninen in Hesiods Theogonie. Mit einem Nachtrag zu Natura varie ludens. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner.

Eco, U. (2009). La vertigine della lista. Milano: Bompiani.

Eichner, H., R. Nedoma (2000–2001a). Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche: Philologische und sprachwissenschaftliche Probleme aus heutiger Sicht. Die Sprache 1–2(42): 1-195

- (2000–2001b). Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche: Philologische und sprachwissenschaftliche Probleme aus heutiger Sicht. Die Sprache 42(1–2): 1-195

Faraone, C.A. (1991). Binding and Burying the Forces of Evil: The Defensive Use of “Voodoo Dolls” in Ancient Greece. Classical Antiquity 10(2): 165-205

- (2001). Ancient Greek Love Magic. Cambridge, Mass. etc.: Harvard University Press.

Geldner, K.F. (1951–1957). Der Rig-Veda. Aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche übersetzt und mit einem laufenden Kommentar versehen. Cambridge, London, Wiesbaden: Harvard University Press.

Gonda, J. (1959). Stylistic Repetition in the Veda. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Goody, J. (1977). The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- (1986). The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, R. (2000). “What's in a list?”: Listing in Greek and Graeco-Roman Malign Magical Texts. In: The World of Ancient Magic: Papers from the First International Samson Eitrem Seminar at the Norwegian Institute at Athens, 4–8 May 1997, Athens, May 1997 Ed. by D.R. Jordan, H. Montgomery, H. M.. Papers from the Norwegian Institute at Athens 4. Bergen: Norwegian Institute at Athens 239-277

- (2002). Shaping the Text: Theory and Practice in Graeco-Egyptian Malign Magic. In: Kykeon: Studies in honour of H.S. Versnel Ed. by H.E.J. Horstmannhoff, H.W. Singor, H. S., Straten H.W.. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, 142. Leiden: Brill 69-111

Graf, F. (1997). Magic in the Ancient World. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Griffiths, A. (2002). Aspects of the Study of the Paippalāda AtharvaVedic Tradition. In: Ātharvaṇá (A Collection of Essays on the AtharvaVeda with Special Reference to its Paippalāda Tradition) Ed. by A. Ghosh. Kolkata/Calcutta: Brill

- (2003). The Textual Divisions of the Paippalāda Saṃhitā. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 47: 5-35

- (2004). Paippalāda Mantras in the Kauśikasūtra. In: The Vedas. Text, Language & Ritual Ed. by A. Griffiths, J.E.M. Houben. Groningen Oriental Studies 20. Groningen: Egbert Forsten 49-99

- (2007). The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalāda School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caraṇavyūhopaniṣad. In: The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition Ed. by A. Griffiths, A. Schmiedchen. Indologica Halensis/Geisteskultur Indiens. Texte und Studien 11. Aachen: Shaker 141-193

- (2009). The Paippalāda Saṃhitā of the Atharvaveda. Kāṇḍas 6 and 7. A New Edition with Translation and Commentary. [Orig.: PhD thesis, University of Leiden, 2004]. Groningen: Forsten.

Griffiths, A., A. Lubotsky (2000–2001). To heal an open wound: with a plant. Die Sprache 42(1–2): 196-210

Güntert, H. (1921). Von der Sprache der Götter und Geister. Bedeutungsgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur homerischen und eddischen Göttersprache. Halle: Max Niemeyer.

Keith, A.B. (1914). The Veda of the Black Yajus School entitled Tattirīya Saṃhitā. Translated from the original Sanskrit prose and verse. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Klaus, K. (1986). Die altindische Kosmologie. Nach den Brāhmaṇas dargestellt. Bonn: Indica et Tibetica.

Klein, J.S. (2000). Polyptoton and Paronomasia in the Rigveda. In: Anusantatyai. Festschrift für Johanna Narten zum 70. Geburtstag Ed. by A. Hintze, E. Tichy. Dettelbach: Röll 133-155

- (2006). Aspects of the Rhetorical Poetics of the Rigveda. In: La langue poétique indo-européenne. Actes du Colloque de travail de la Société des Études Indo-Européennes (Indogermanische Gesellschaft / Society for Indo-European Studies), Paris, 22–24 octobre 2003 Ed. by G.-J. Pinault, D. Petit. Collection linguistique, publiée par la Société de Linguistique de Paris, 91. Leuven: Peeters 195-211

Kühlmann, Wilhelm (1973) Katalog und Erzählung. Studien zu Konstanz und Wandel einer lite- rarischen Form in der antiken Epik. phdthesis. Universität Freiburg im Breisgau

Kuhn, A. (1864). Indische und germanische Segenssprüche. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete des Deutschen, Griechischen und Lateinischen.

Landsberger, B., W. Soden (1965 & 1974). Die Eigenbegrifflichkeit der babylonischen Welt. Leistung und Grenze sumerischer und babylonischer Wissenschaft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Larsen, M.T. (1987). The Mesopotamian Lukewarm Mind: Reflections on Science, Divination, and Literacy. In: Language, Literature, and History: Philological and Historical Studies Presented to Erica Reiner Ed. by F. Rochberg-Halton. American Oriental Series 67. New Haven, Conn.: American Oriental Society 203-225

Lelli, D. (2009) Atharvaveda-Paippalāda: Kāṇḍa quindicesimo: uno studio preliminare. phdthesis. Università degli Studi di Firenze

Liebich, B. (1919). Zur Einführung in die indische einheimische Sprachwissenschaft. II: Historische Einführung und Dhātupāṭha.. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

Lommel, H. (1927). Die Yäšt's des Awesta, übersetzt und eingeleitet. Mit Namenliste und Sachver- zeichnis. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

Lopez, C. (2010). Atharvaveda-Paippalāda: Kāṇḍas Thirteen and Fourteen. Text, Translation, Commentary. Cambridge, Mass.; Columbia: Department of SanskritIndian Studies, Harvard University; South Asia Books.

Lubotsky, A. (2002). Atharvaveda-Paippalāda. Kāṇḍa Five. Text, Translation, Commentary. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press.

Oldenberg, Hermann (1919). Vorwissenschaftliche Wissenschaft: die Weltanschauung der Brāhmaṇatexte. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Oppenheim, A.L. (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia. Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- (1978). Man and Nature in Mesopotamian Civilization. In: Dictionary of Scientific Biography Ed. by C.C. Gillipie. New York: American Council of Learned Societies 634-666

Panagl, O. (1999). Ein bukolisches Problem. In: Compositiones Indogermanicae in memoriam Jochem Schindler. Hrsg. von Heiner Eichner und Hans Christian Luschützky unter redaktioneller Mitwirkung von Velizar Sadovski Prag: Enigma Corporation 437-445

Panaino, A. (2002). The Lists of Names of Ahura Mazdā (Yašt I) and Vayu (Yašt XV). Rome: Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente.

- (forthcoming). The Nyayišn Corpus and Its Relationships with the Yašts. The Case of Yašts 6 and 7.

Pinault, G.-J., D. Petit (2006). La langue poétique indo-européenne. Actes du Colloque de travail de la Société des Études Indo-Européennes. Leuven: Peeters.

Raster, P. (1992). Phonetic Symmetries in the First Hymn of the Rigveda. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

Sadovski, V. (2002). Dvandva, tatpuruṣa and bahuvrīhi: On the Vedic Sources for the Names of the Compound Types in Pāṇini's Grammar. In: Nominal Composition in Indo-European, ed. by Torsten Meißner and James Clackson. Transactions of the Philological Society 100(3): 351-402

- (2006). Dichtersprachliche Stilmittel im Altiranischen und Altindischen. Figurae elocutionis, I: Stilfiguren der Ausdrucksweitung. In: Indogermanica. Festschrift für Gert Klingenschmitt. Indische, iranische und indogermanische Studien, dem verehrten Jubilar dargebracht zu seinem fünfundsechzigsten Geburtstag Ed. by G. Schweiger. Taimering: VWT-Verlag 521-540

- (2007). Epitheta und Götternamen im älteren Indo-Iranischen. Die hymnischen Namenkataloge im Veda und im Avesta (Stilistica Indo-Iranica, I.). Fascicle II of: Panaino, Antonio – Sadovski, Velizar: Disputationes Iranologicae Vindobonenses, I.. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- (2008). Syntax und Formulierungsstil in der indo-iranischen Dichtersprache: Einleitendes zum Periodenbau und einigen figurae per ordinem im Avesta und Veda. In: Iran und iranisch geprägte Kulturen: Studien zum 65. Geburtstag von Bert G. Fragner. Beiträge zur Iranistik 27 Ed. by M. Ritter, B. Hoffmann, B. H.. Wiesbaden: Reichert 242-255

- (2009). Ritual Formulae and Ritual Pragmatics in Veda and Avesta (= h. Die Sprache 48: 156-166

- (2012). Ritual Spells and Practical Magic for Benediction and Malediction in Indo-Iranian, Greek, and Beyond (Speech and performance in Avesta and Veda, I). In: Iranistische und indogermanistische Beiträge in memoriam Jochem Schindler (1944–1994). Ed. by V. Sadovski, D. Stifter. Sitzungsberichte der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Phil.-hist. Klasse, 832. Band: Veröffentlichungen zur Iranistik, 51. Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften 331-350

Schmitt, R. (2003). Onomastische Bemerkungen zu der Namenliste des Fravardīn Yašt. In: Religious Themes and Texts of Pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia. Studies in Honour of Professor Gherardo Gnoli on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday on 6th December 2002 Ed. by C.G. Cereti, M. Maggi, M. M.. Wiesbaden: Reichert 363-374

Selz, G. (2007). Offene und geschlossene Texte: Zu einer Hermeneutik zwischen Individualisierung und Universalisierung. In: Was ist ein Text? Alttestamentliche, ägyptologische und altorientalistische Perspektiven Ed. by S. Schorch, L. Morenz. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft—Beihefte, 362. Berlin: De Gruyter 64-90

- (2011). Remarks on the Empirical Foundation of Early Mesopotamian Knowledge Acquisition. In: The Empirical Dimension of Ancient Near Eastern Studies Ed. by G. Selz. Vienna: Lit Verlag Wien 49-70

- (forthcoming) Classifiers and Classifications in Cuneiform Studies.

Soden, W. von (1936). Leistung und Grenze sumerischer und babylonischer Wissenschaft. In: Die Welt als Geschichte [Repr. (enlargedcorr.) in B. LandsbergerW. von Soden, 1965; 1974] 411-464

Spufford, F. (1989). The Chatto Book of Cabbages and Kings: Lists in Literature. London: Chatto & Windus.

Veldhuis, N. (1997) Elementary Education at Nippur. The Lists of Trees and Wooden Objects. phdthesis. University of Groningen

- (1999). Continuity and Change in the Mesopotamian Lexical Tradition. In: Aspects of Genre and Type in Pre-Modern Literary Cultures Ed. by B. Roest, H.L.J. Vanstiphout. Groningen: Styx 101-118

- (2004). Religion, Literature, and Scholarship: The Sumerian Composition Nanše and the Birds. With a Catalogue of Sumerian Bird Names. Leiden: Brill.

- (2006a). How Did They Learn Cuneiform? “Tribute/Word List C” as an Elementary Exercise. In: Approaches to Sumerian Literature in Honour of Stip (H.L.J. Vanstiphout) Ed. by P. Michalowski, N. Veldhuis. Leiden: Brill 181-200

- (2006b). How to Classify Pigs: Old Babylonian and Middle Babylonian Lexical Texts. In: De la domestication au tabou: le cas des suidés dans le Proche-Orient ancien Ed. by C. Michel, B. Lion. Paris: De Boccard 25-29

Watkins, C. (1995). How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

West, M.L. (1985). The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women: Its Nature, Structure and Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Whitney, W.D., C.R. Lanman (1905). Atharva-Veda Saṁhitā. Translated with a Critical and Exegetical Commentary by William Dwight Whitney [...]. Revised and Brought Nearer to Completion and Edited by Charles Rockwell Lanman.. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Witzel, M. (1985). Die Atharvaveda-Tradition und die Paippalāda-Saṃhitā. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft Supplementband VI: 256-271

- (1997). The Development of the Vedic Canon and Its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu. In: Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts Ed. by M. Witzel. Harvard Oriental Series: Opera Minora, 2. Cambridge (Mass.): South Asia Books 257-345

Zehnder, T. (1993) Vedische Studien—Textkritische und sprachhistorische Untersuchungen zur Paippalāda-Saṃhitā. Kāṇḍa 1. phdthesis. Universität Zürich

- (1999). Atharvaveda-Paippalāda. Eine Sammlung altindischer Zaubersprüche vom Beginn des 1. Jahrtausends v. Chr. Buch 2: Text, Übersetzung, Kommentar. Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner.

Zysk, K.G. (1998). Medicine in the Veda. Religious Healing in the Veda. With Translations and Annotations of Medical Hymns from the Ṛgveda and the Atharvaveda and Renderings from the Corresponding Ritual Texts.. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Footnotes

For a characterization of lists of divine names as a (cross-cultural) form of religious poetry, see (Sadovski 2007, esp. 38–47; Panaino 2002, 15–24, 107ff.).

See (Soden 1936, 555ff.); for the analysis of the (philological and extra-philological) background of his theses, see (Veldhuis 1997, 6f., 137–139); on the assessment of Mesopotamian catalogues from an epistemological perspective, cf. also (Oppenheim 1977, 248; Oppenheim 1978, 634ff.; Larsen 1987, esp. 210, 218).

The connection between representation of knowledge in forms of catalogues and mnemonical/pedagogical practice in ancient Mesopotamia has been investigated by Niek Veldhuis in a series of articles (e.g. Veldhuis 1999; 2006a; 2006b) and a special monograph (idem 1997; cf. also Veldhuis 2004); on the implications of this text genre for hermeneutics and historiography of knowledge see (Kühlmann 1973) and recently (Selz 2007, 2011).

On lists in Ancient Greek and Graeco-Egyptian magic see Richard Gordon’s contributions (Gordon 2000, 250–263), on archaic and classical lists, as well as ibid. (263–275), on cross-culturally influenced Hellenistic lists; cf. also (Gordon 2002); for a metanalytical point of view on Ancient Indian lists in grammar and ritual and their Buddhist correspondents in the plurilingual conditions of Indian, Central Asia and Chinese Turkestan see (Braarvig et.al. forthcoming).

(Goody 1977, esp. 74–111), modified in (Goody 1986; 1987) as well as, generally, (Gordon 2000, 244f., 250), and (Braarvig 2000, with lit.), on the heuristic value of Goody’s ‘Grand Dichotomy’ concept.

See recently (Eco 2009). One has to recall that this semiotic monograph on lists was intent to accompany—but, in a certain sense, has itself been accompanied by—a concomitant exposition of classical and modern pictures representing ‘catalogues’ of various spheres of life—styled by the Italian scholar at the Musée du Louvre as a kind of super-list which, moreover, went hand in hand with its own analytical meta-list in a kind of transcendental, ultra-Goedelian (or proto-Münchhausen-ian?) attempt of a system to find a meta-language about itself.

See (Spufford 1989). From the flood of works on catalogues in classical works of oral poetry like the ones by Homer and Hesiod, I shall quote here only (Deichgräber 1965) and (West 1985), each one emblematic for the research accents of its period, characterized by high-level intrinsic comparison and giving certain extrinsic, comparative perspectives—but almost completely lacking contrastive interest in typological parallels in non-‘Classical’ (in the [Indo-]Euro-centric sense of this term) languages and literatures.

Multilingualism, Linguae Francae, and the Global History of Religious and Scientific Concepts. An international conference, Norwegian Institute at Athens, April 2–5, 2009, convenors: Jens E. Braarvig and Malcolm Hyman†.

Classification as a Hermeneutic Tool. A Workshop at the Oriental Institute, Vienna University, November 2, 2009, convenor: Gebhard Selz. Cf. http://www.univie.ac.at/orges/hp/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/Classification_plakat.pdf (accessed June 10, 2014). See also (Selz forthcoming).

Multilingual Lists, Catalogues, and Classification Systems. A workshop within the Interdisciplinary Conference Multilingualism in Central Asia, Near and Middle East from Antiquity to Early Modern Times, organized by the Institute of Iranian Studies and the International Relations Department of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, March 1–3, 2010, convenors: Bernhard Plunger, Velizar Sadovski, Florian Schwarz. Cf. http://www.oeaw.ac.at/iran/german/konferenz_multilingualism.html (accessed June 10, 2014).

Lists, Catalogues, and Classification Systems from Comparative and Historical Point of View. A workshop of the Multilingualism Research Group, held in the framework of the Interdisciplinary Conference Multilingualism and History of Knowledge in Asia from Antiquity till Early Modern Times, Vienna, November 3–5, 2011, organized by the Institute of Iranian Studies and the International Relations Department of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, November 3–5, 2011; convenors like in Fn. 10.

Crossing Boundaries: Multilingualism, Lingua Franca and Lingua Sacra, TOPOI conference, Berlin, November 8–10, 2010, convenor: Markham J. Geller. Cf. http://www.topoi.org/event/crossing-boundaries-multilingualism-lingua-franca-and-lingua-sacra/ (accessed June 10, 2014).

Problems of lists in magical and medical texts have been discussed in a series of papers on the TOPOI Conference Knowledge to Die For: Transmission of Prohibited and Esoteric Knowledge through Space and Time, Berlin, May 2–4, 2011, convenor: Florentina Badalanova Geller. Cf. http://www.topoi.org/event/knowledge-to-die-for-transmission-of-prohibited-and-esoteric-knowledge- http://through-space-and-time/ (accessed June 10, 2014); in preparation is a joint publication of Geller, Badalanova Geller, and Sadovski on the materials discussed in the framework of the two Berlin meetings at the Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science.

Organization of knowledge in Asian cultures: Lists, catalogues and classification systems between orality and scriptuality. Panel in the framework of the 31st German Congress of Oriental Studies, Marburg, September 20–24, 2010, convenors: Jens E. Braarvig, Markham J. Geller and Velizar Sadovski. Cf. http://https://archive.today/o/QKkC6/http://www.dot2010.de/index.php?ID_seite=5.

Multilingualism and Social Experience in Pre-Modern Societies of Ancient Eurasia: Socio-Economic, Linguistic, and Religious Aspects. Panel in the framework of the 32nd German Congress of Oriental Studies, Münster, September 23–27, 2013, convenors: Velizar Sadovski and Gebhard J. Selz. Cf. http://www.dot2013.de/en/programm/abstracts/panel http://-multilingualism-and-social-experience-in-pre-modern-societies-of-ancient-eurasia-socio-economic http://-linguistic-and-religious-aspects/, accessed June 10, 2014.

Abbreviations of texts used: (a) Vedic: RV = R̥gveda-Saṃhitā. – AVŚ = Atharvaveda-Saṃhitā (Śaunaka branch); AVP = Atharvaveda-Saṃhitā, Paippalāda branch; Kauś = Kauśika-Sūtra. – YV(S/B) = Yajurveda(-Saṃhitā/-Brāhmaṇa), esp.: Black YV: TS = Taittirīya-Saṃhitā. TB = Taittirīya-Brāhmaṇa. BaudhŚS = Baudhāyana-Śrauta-Sūtra. ĀpŚS = Āpastamba-Śrauta-Sūtra. White YV: Vājasaneyi-Saṃhitā; ŚB = Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa. (b) Avestan: text strata – GAv. = Gāthic Avestan. YAv = ‘Young(er)’ Avestan; text corpora – Y. = Yasna; Yt. = Yašt; Vd. = Vīdēvdād.

For relevant texts edited and/or examined so far in the framework of this project, cf. e.g. (Witzel 1985 (AVP and AVŚ); Witzel 1997; Zehnder 1993 (AVP, Kāṇḍa 1); Zehnder 1999 (Kāṇḍa 2); Lubotsky 2002 (Kāṇḍa 5); Griffiths 2002, 2003, 2004 (AVP and Kauś.), 2007, 2009 (Kāṇḍa 6 and 7), Lopez 2010 (Kāṇḍa 13 and 14), and Lelli 2009 (Kāṇḍa 15)).

Edited by S. Bahulkar, Jan Houben, Michael Witzel and Julieta Rotaru, to appear 2015.

Included in the materials collected in the volume (Braarvig et.al. forthcoming).

Cf. (Panaino 2002; Schmitt 2003; Sadovski 2007), e.g. on the Indian ‘name-praising hymns,’ nāma-stotras.

I refer to the analysis of the formation of the compounds and the ‘natural’ character of the connections between their elements (like in the case of ‘rice-and-barley’) in (Sadovski 2002, 358–361, with notes 387–389).

For more cosmological lists, mainly in the YV(Br), and their structures, see the choice of texts in (Klaus 1986).

Noteworthy, the same formulaic sequences of domestic animals occur in the purification/lustration formula of TB. cited below, § 1.3.

Cf. (Panagl 1999, 443, with lit., 445, n. 20).

On these as well as on the conclusive formulae of the Yašts (in their relationship with the Nyayišn corpus) cf. (Darmesteter 1892, 331–334; Lommel 1927, 8ff.) and most recently (Panaino forthcoming).

Cf. (Zysk 1998, 15f.).

Cf. (Kuhn 1864, 49ff.).

(Eichner and Nedoma 2000–2001b), esp. in the essay (Eichner and Nedoma 2000–2001a). Cf. also the divergent interpretative proposals by Wolfgang Beck in Part 2 of the same volume.

(West 2007, 336); for modifications cf. the comm. by (Eichner and Nedoma 2000–2001b, ad loc.).

(Griffiths and Lubotsky 2000–2001), see also p. 209 with a photograph of the ms. Ku 1, fol. 78r.

On the notion of glosso-lalía see (Güntert 1921, 23–54, esp. 30f.) and cf. (Sadovski 2012) on concepts of the sphere of laletics and their Indo-Iranian dimensions (japa-; vipra- language etc.).

See (Sadovski 2006, 530).

See (Raster 1992, 22).

See (Keith 1914, 1, 4; Deeg 1995, 65).

Details in (Sadovski 2006, 534f.).

Cf. (Gonda 1959, 332), after H. R. Diwekar.