7.1 Science and Myth

Since the problem of demarcation between science and

This differentiation seems to separate two completely different intellectual activities. While the objectives of science include the acquisition of

The legendary character of the “historical” omens, and the impossibility of some of the ominous events (such as the moon being eclipsed on the 20th day), strongly suggest that whatever was the basis of Babylonian divination, it was not empirical fact. Empiricalobservation may have played its part, but it was not fundamental. The solution must be sought elsewhere. Our own natural sciences are based on a premise so simple that it is usually taken for granted: things behave according to universally valid laws. It is our task to discover those laws, and the means to do so is observation, supported by the controlled experiment. In a similar fashion, Babylonian divination is based on a very simple proposition: things in the universe relate to one another. Any event, however small, has one or more correlates somewhere else in the world. This was revealed to us in days of yore by the gods, and our task is to refine and expand that body of knowledge. The means to do so is mystical speculation supplemented by observation. There is no evidence that the Mesopotamian scholars ever attempted to verify the results of their speculations by experiment. Nevertheless, the Neo-Assyrian astrologers undoubtedly believed in their craft and found it confirmed by events. For example, in Las 298, Akkullanu tells the king that “the series says in connection with this nisan eclipse: ‘If Jupiter is present in the eclipse, all is well with the king, a noble dignitary will die in his place.’ Did the king pay attention to this? A full month has not yet passed (before) his chief judge lay dead!” Koch-Westenholz 1995, 18–19

Since we know, from the surviving correspondence, the titles, work designations and even the salaries of the scholars who worked for the kings of the period, one can incontrovertibly state that no professional distinction existed between the realm of

Thesis 1 No two

The confirmation—or refutation—of this thesis needs to take into account the inferential treatment of an object of knowledge: if it is taken as the unequivocal assumption about conclusions and if it carries the burden of proof, this is taken to be a good indication that the people consider the assumption to be knowledge. Errors in their beliefs may be possible. The question of what is knowledge or what is known in antiquity cannot be adequately answered by reflective philosophical statements. Neither can it be decided upon by a linguistic analysis of words such as episteme or techne, nor even by the philosophical analysis of Plato’s view of knowledge as justified true belief. More important is the practice of how knowledge is established and used in a critical epistemic context.

Thesis 2 In ancient societies knowledge is characterized by the way it is established and is used for inferential derivations, and its potential to criticize other propositions.

This movement away from content to the function of knowledge should lead to the classes of ancient texts being revised as either scientific or mythical according to modern

A good example of how disciplinary distinctions can mislead the systematic interpretation of texts are the so-called astronomical diaries.1 The title alone might send someone off in the wrong direction. For instance, the diaries record not only astronomical events, but also a large class of other equally important occurrences. Furthermore, it is all but clear whether they were recorded and compiled in the way that we write diary entries today. The

7.2 Empirical Basis

One oft-cited tablet of the diaries stands out on account of certain remarkable entries. In all other respects—reported content and formal linguistic structure—it is representative of the group of texts. The following translation and emendation is given by Bert van der Spek. Although the beginning of the tablet, which would include the complete date, is missing, the date can be reconstructed as year 5 of Darius III, month 6. It then continues in the following typical schematic manner:2

Day 13 [20 September]: Sunset to moonrise: 8°. There was a lunar eclipse. Its totality was covered at the moment when Jupiter set and Saturn rose. During totality the west wind blew, during clearing the east wind. During the eclipse, deaths and plague occurred.

Day 14: All day clouds were in the sky.

Day 15: Sunset to moonrise: 16°. There were clouds in the sky. The moon was 3 2/3 cubits below [the star] Alpha Arietis, the moon having passed to the east. A meteor which flashed, its light was seen on the ground; very overcast, lightning flashed. […]

Daily entries concerning

That month, the equivalent for 1 shekel of silver was: barley [lacuna] kur; mustard, 3 kur, at the end of the month [lacuna]; sesame, 1 pân, 5 minas. At that time, Jupiter was in Scorpio; Venus was in Leo, at the end of the month in Virgo; Saturn was in Pisces; Mercury and Mars, which had set, were not visible. That month, the river level was [lacuna].

The sensational additional entry of this tablet reports the downfall of the empire and the defeat of Darius III by Alexander the Great at the battle of Gaugamela:

On the 11th of that month, panic occurred in the camp before the king. The Macedonians encamped in front of the king.

On the 24th [1 October], in the morning, the king of the world [Alexander] erected his standard and attacked. Opposite each other they fought and a heavy defeat of the troops of the king [Darius] he [Alexander] inflicted. The king [Darius], his troops deserted him and to their cities they went. They fled to the east.

This report is not only remarkable because of the events that it records. For the

Thesis 3 In Mesopotamia scientific practices and knowledge acquisition persist throughout periods of social change. Scientific knowledge remains largely unaffected by changing cultural contexts and serves the same purpose to different users.

At first glance the events seem to have been observed in a casual way and chronologically noted by one scholar. Yet a systematic analysis of these reports shows that they were formally and strictly arranged for each month, so that the entries resemble monthly reports containing systematic

Obv.1: year 156, month xi, (the 1st of which was identical with) the 30th (of the preceding month), sunset to moonset: 18°; measured(?) (despite of) clouds(?) […]2: night of the 1st, all night very overcast; the south wind which was slanted to the east blew […]3: the south wind which was slanted to the east blew. Night of the 2nd, all night very overcast; to […]4: the south wind blew. Night of the 3rd, all night very overcast. The 3rd, clouds were in the sky. Ni[ght of the 4th, (…)]5: the moon was 4 cubits belowh piscium. The 4th, clouds and thin fog were in the sky […]6: in the afternoon, very overcast, the south wind blew. Night of the 5th, clouds were in the sky; the moon was 6 cubits belowa arietis,7: the moon having passed […] cubit to the east; all night very overcast, the south wind blew.

Even though the

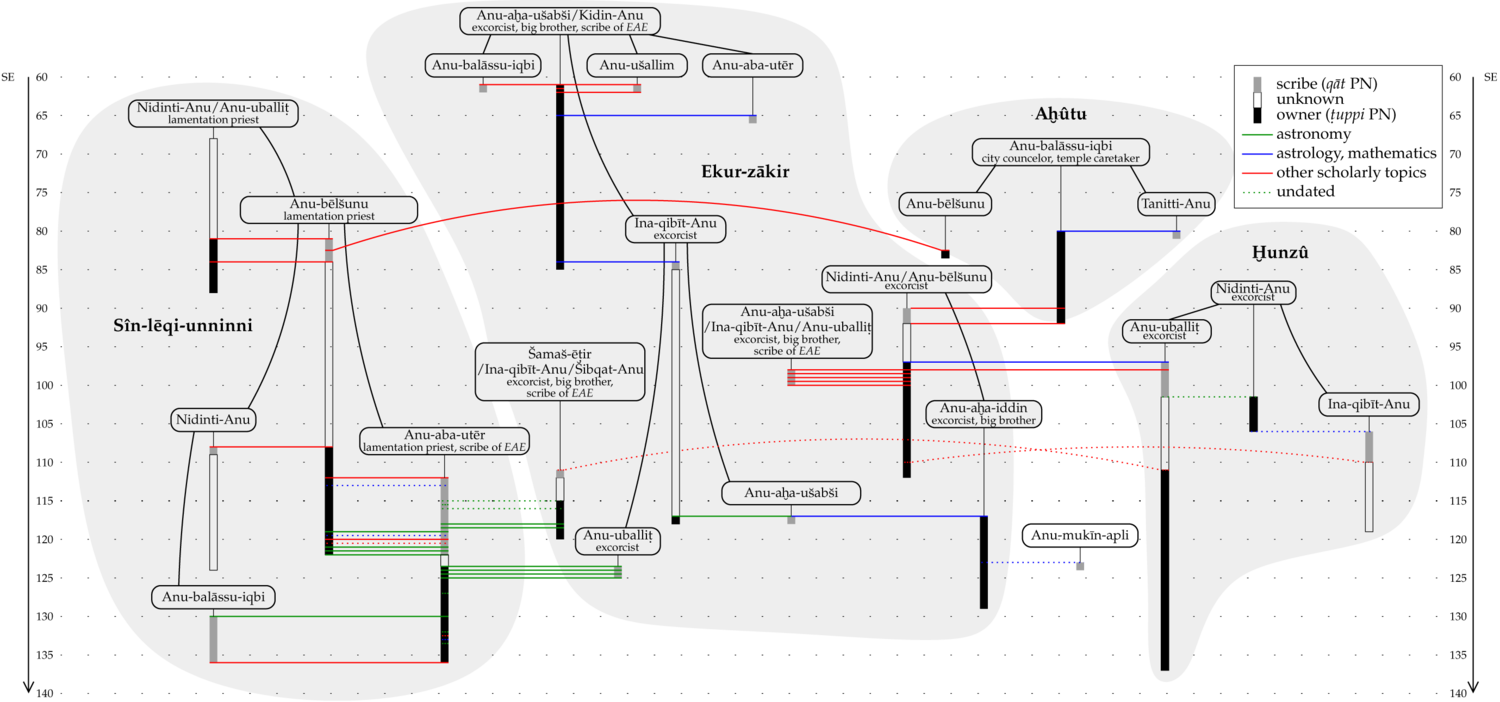

The signatures of the observers were not commonly recorded. In contrast to the diaries, as Mathieu Ossendrijver showed, theoretical astronomical texts authored in Uruk show the names of the tablets’ ‘owners’ and those of the scribes. Figure 7.1 shows the temporal distribution of scholarly activities undertaken in Uruk during the Seleucid era, the years of which form the diagram’s y-axis. A vertical bar represents the time period during which scholarly activities were carried out. The shallow (grey) bars show the scribe’s activities; the solid (black) bars the activities of a tablet’s “owner.” Every tablet carries two names—that of the owner and that of the scribe—which are connected in the diagram by means of horizontal lines. The continuous (grey) background colour of the diagram shows that the activities were undertaken by only a few families. Although in most cases the owner and scribe came from the same family, there are notable exceptions. A scholar always started his career as a scribe. Once promoted to “owner,” he is never recorded as working as a scribe again. Some entries make it clear that the ‘owner’ checked the validity of the tablet produced by the scribe. Therefore, the main function of the owner’s name on the tablet was to take responsibility for its validity. The system established a form of quality control at the report and copy producing level. The

Fig. 7.1: Schematic diagram showing the engagement of scholars as writers and “owners” of the

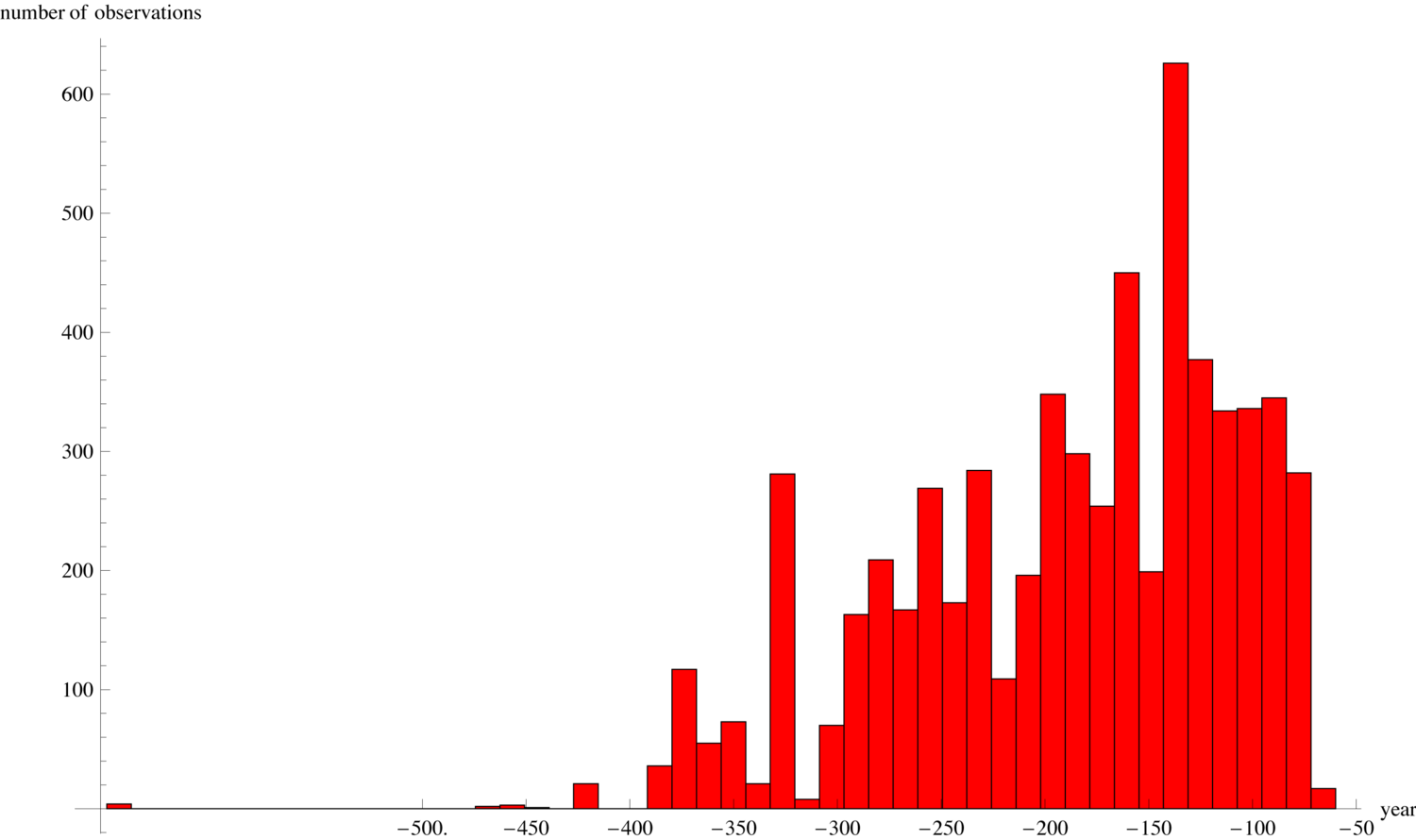

Fig. 7.2: Distribution of observations in the astronomical diaries. The increase in activity in later times is due to distortions from the archaeological findings.

Even when the observations were carried out by several people at different places, their reports were collected, critically examined and synthesized into one representative datum, which consequently lost its individual observational background. The names of the observers are no longer an indication of the tablets’ validity. Both the astronomical events as well as the summarized economic data were gathered in standardized ways. They were not exposed to the coincidental market observations of scholars who happened to be buying items at the weekly market. The

Thesis 4 As a source of empirical data, the astronomical diaries were systematically checked by a group of researchers. This communal effort was required in order to obtain a comprehensive and reliable data resource. Consequently, the empirical data therein are more than just the “protocol sentences” of individual observers.

The long-term comparison of

Thesis 5 The astronomical diaries are formal, observational recordings of momentous events that took place in the fields of astronomy, meteorology, economics and state, which were documented in the form of monthly reports.

7.3 Regularities as Scientific Hypothesis

7.3.1 First-Order Regularities

The

7.3.2 The Concept of Signs

A citation from Hermann Hunger and David Pingree lays down the standard view of the kind of knowledge that early Babylonian scholars were seeking:

Omens can also be classified according to their predictions: some omens concern the king, the country, or the city; others refer to private individuals and their fortunes. One thing is to be kept in mind: the gods send the signs; but what these signs announce is not unavoidable fate. A sign in a Babylonian text is not an absolute cause of a coming event, but a warning. By appropriate actions one can prevent the predicted event from happening. The idea of determinism is inherent in this concept of sign. The knowledge about the signs is however based on experience: once it was observed that a certain sign had been followed by a specific event, it is considered known that this sign, whenever it is observed again, will indicate the same future event. So while there is an empirical basis for assuming a connection between sign and following event, this does not imply a notion of causality. Hunger 1999, 5

Though somehow empirically based, what exactly this kind of knowledge was remains obscure. Signs are certainly not absolute causes (who ever said that they were?), but what is the epistemology of a “warning”? Ancient scholars undoubtedly wanted to obtain knowledge about the connections between certain events, so that they could intervene and perhaps prevent an otherwise probable future event from occurring. Medical doctors find themselves in the same diagnostic and therapeutic situations: symptoms are analyzed in order to deduce unknown causes for illnesses, which hopefully can be cured or even prevented from happening. Yet this would only work if causal interactions were presumed, which is precisely what the Babylonians did for all kinds of regularities.

Thesis 6 In Babylonian scholarship there is no methodological difference between

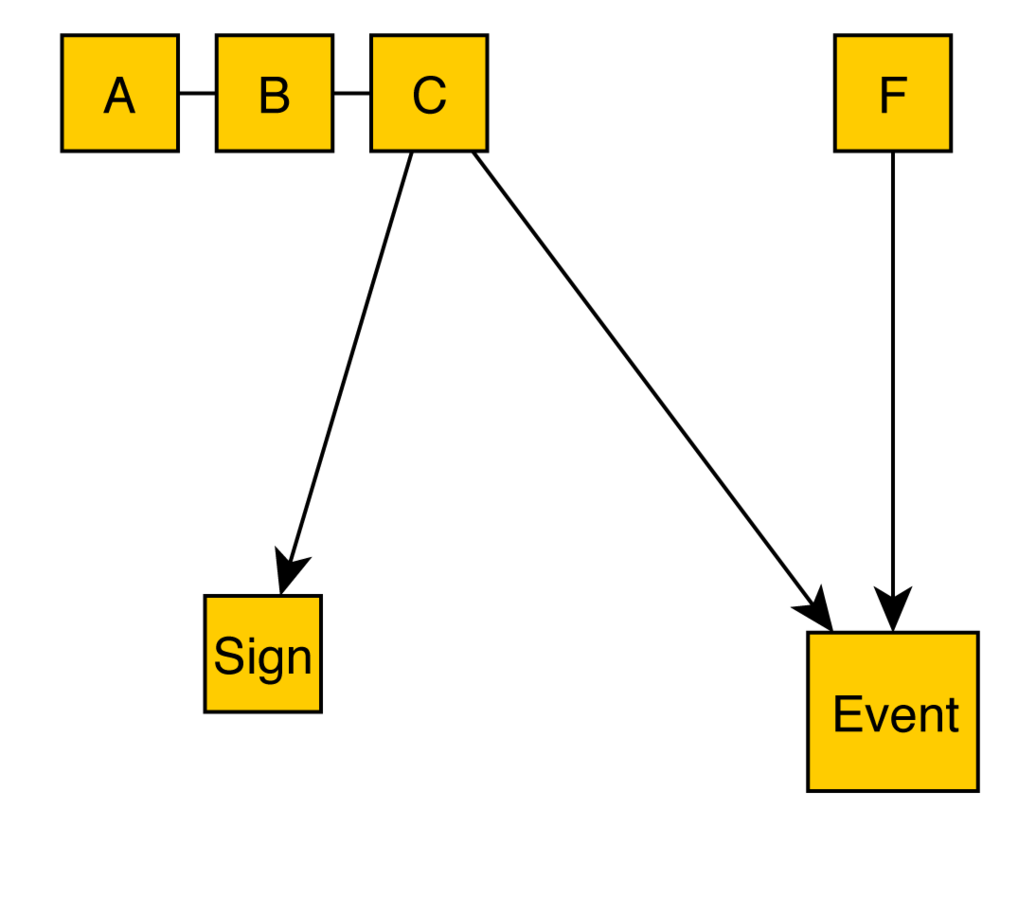

Fig. 7.3: An epiphenomenal causal diagram for signs and effects.

The reason for the widespread misunderstanding of early

Almost all omens are formulated as conditional clauses, “if x happens, then y will happen.” The first part is called the protasis, the second part the apodosis. Hunger 1999, 5

It is common opinion that the logical form of omens, like many other Akkadian sentences that express regular occurrences, has the logical form of a material conditional: if-then relations are logically false only if the antecedent is true and the consequent false.

Yet, a number of different meanings could be read from the grammatical form of the construction, which starts with the word šumma, and is followed by the antecedent or protasis and then by a consequent (apodosis):

material conditional: “if socrates is a philosopher, then he is a wise man.”

definitional assignment: “if he is a bachelor, he has no wife.”

causal regularity: “if you strike the match, it will light.”

decisional sentence: “if you obey, you will succeed.”

For the interpretation it is sufficient to study the use of such regularity expressions in order to determine their meanings.

Thesis 7 Expressions of regularity in early science denote complex causal structures such as epiphenomena.

7.3.3 Rules of Inference

In A Babylonian Diviner’s Manual, an ancient text edited by Leo Oppenheim, some rules of inference are articulated for the ancient scholar:

The signs in the sky just as those on the earth give us signals. […] Their good and evil portents are in harmony [i.e., confirming each other]. The signs on earth just as those in the sky give us signals. Sky and earth both produce portents; though appearing separately, they are not separate [because] sky and earth are related. A sign that portends evil in the sky is [also] evil on earth, one that portends evil on earth is evil in the sky. When you look up a sign [in these omen collections], be it one in the sky or one on earth, and if that sign’s evil portent is confirmed, then it has indeed occurred with regard to you in reference to an enemy or to a disease or to a famine. Check [then] the date of that sign, and should no sign have occurred to counteract [that] sign, should no annulment have taken place, one cannot make [it] pass by, its evil [consequences] cannot be removed [and] it will happen. Oppenheim 1974, 203–205

The following list of regularities is grouped according to phenomena. It is clear that the finding of regularities is an empirical question. The protasis is described as:

| (25) | “if the sky is constantly covered with a haze” |

| (26) | “if after the sun has moved higher, |

| a star shoots and comes to a stop in front of it” | |

| (27) | “if the planet Venus becomes stationary in the morning |

| and its critical dates” | |

| (28) | “if the planet Mars which has seven names is seen |

| on the day of (its) opposition” | |

| (29) | “if the opposition of moon and sun” |

| (30) | “if the first visibility of the moon and its ‘tiaras’ ” |

| (31) | “if the moon is constantly surrounded by a halo |

| from the first to the fifth (var. thirtieth) day” | |

| (32) | “if a star is seen that has a crest in front and a tail behind |

| and the sky turns light” | |

| (33) | “if Adad sends lightning and his ‘hand’ is seen together |

| with the lightning” | |

| (34) | “if the constellation Pegasus is seen in the month Nisannu” |

| (35) | “if a rainbow that is curved like the intestine(s) is seen in the sky” |

The diviner’s manual predates the

(47–52) These are the things you have to consider when you study the two collections [called] “if from the month Arahsamna on” [and] “if a star has a crest in front.” [when] you have identified the sign and [when] they ask you to save the city, the king and his subjects from enemy, pestilence and famine [predicted] what will you say? when they complain to you, how will you make [the evil consequences] bypass [them]?

It is important that all regularities are temporally determined. Therefore, all regularities are intrinsically linked to time periodicities, which are determined by astronomical periods.

(53–63) In summa twenty-five tablets with signs [occurring] in the sky and on earth whose good and evil portents are in harmony you will find in them every sign that has occurred in the sky [and] has been observed on earth. This is the method to dispel [them]:

(57–63) Twelve are the months of the year, 360 are its days. Study the length of the year and look [in tablets] for the timings of the disappearances, the visibilities [and] the first appearance of the stars, [also] the position of the Iku star at the beginning of the year, the first appearance of the sun and the moon in the months Addaru and […] Flu, the risings and first appearances of the moon as observed each month; watch the ‘opposition’ of the Pleiades and the moon, and [all] this will give you the [proper] answer, [thus] establish the months of the year [and] the days of the months, and do perfectly whatever you are doing.

The last sentence serves as a warning (and encouragement) to scholars to practise according to

Some of the

(64–65) Should it happen to you that at the first visibility of the moon the weather should be cloudy, [the water clock(?)] should be the means of computing it, should it happen to you that at the disappearance of the moon the weather should be cloudy, the water clock[?] should be the means of computing it.

This is also valid when it comes to making weather prognostications. The following text is particularly interesting, since it contains instructions on how to obtain rules for forecasting the weather, rules that also apply to other

| 1 | [… for rain and flood] water do you have a prediction. |

| 2 | […] month Ajjaru; for Jupiter 72, 24 (or) 12 years; |

| 3 | [for Venus] 16 (or) 8 years; for Mercury 46, 21 (or) 13 years; |

| 4 | [for Mars] 47 years; for the sun 36 (or) 54 years; |

| for the moon 18 years. | |

| 5 | [so much earlier] it was too early, it will be too early (also) now; |

| so much earlier it was too late, it will now be too late (also). | |

| 6 | [so much earlier] there were clouds, there will be clouds (also) now; |

| so much earlier there was thunderstorm, there will thunderstorm | |

| (also) now. | |

| 7 | [much] earlier there was heavy rain, there will be heavy rain |

| (also) now; so much earlier … it was, it will be … now. | |

| 8 | [much] earlier … it was, is will be … now; |

| so much earlier it was downpour, it will be downpour (also) now. | |

| 9 | [much] flooding was during Adad, it will be flooding during adad |

| (also) now; predict mass flood. |

The above rules assume a principle of determinism in conjunction with astronomical periodicities, which always takes into account that additional factors on the conditional part are necessary for the future event is to occur or fail to occur. The text is made up of three parts: astronomical periods, then the statement that some constant time shifts can be applied, concluded by the enlisting of weather phenomena of increasing importance. This is a schema to build regularities of weather prognostications that work as well as schemes for astronomical predictions.

Thesis 8 The text of the diviner’s manual contains instructions on how to make

7.3.4 The Construction of Causal Regularities

There exists an information flow schema that closely follows the instructions of these and similar tables.

The empirical basis is a chronological record of suspicious signs and events, with characteristically first-order regularities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

correlations:

periodicities:

sign periodicities:

Thesis 9 The application of the rule of

Once the

References

Brack-Bernsen, Lis (1993). Babylonische Mondtexte: Beobachtung und Theorie. In: Die Rolle der Astronomie in den Kulturen Mesopotamiens: Beiträge zum 3. Grazer Morgenländischen Symposion (23.–27. September 1991) Ed. by Hannes D. Galter. Grazer morgenländische Studien. Graz: rm-Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft 331-358

- (1997). Zur Entstehung der babylonischen Mondtheorie: Beobachtung und theoretische Berechnung von Mondphasen. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Graßhoff, Gerd (1997). Late Babylonian Astronomical Diaries. In: Ancient Astronomy and Celestial Divination Ed. by Noel Swerdlow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Graßhoff, Gerd, Michael Baumgartner (2004). Kausalität und kausales Schließen: Eine Einführung mit interaktiven Übungen. Bern: Bern Studies in the HistoryPhilosophy of Science.

Graßhoff, Gerd, Michael May (2001). Causal Regularities. In: Current Issues in Causation Ed. by Wolfgang Spohn, Marion Ledwig, M. L.. Paderborn: Mentis Verlag 85-114

Hunger, Hermann (1999). Non-mathematical Astronomical Texts and Their Relationships. In: Ancient Astronomy and Celestial Divination Ed. by Noel M. Swerdlow. Dibner Institute Studies in the History of Science and Technology. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 77-96

Hunger, Hermann, David E. Pingree (1989). MUL.APIN: An Astronomical Compendium in Cuneiform. Archiv für Orientforschung

Koch-Westenholz, Ulla (1995). Mesopotamian Astrology: An Introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian Celestial Divination. Copenhagen: Carsten Niebuhr Institute of Near Eastern Studies.

Neugebauer, O. (1945). The History of Ancient Astronomy. Problems and Methods. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 4(1): 1-38

Neugebauer, Otto (1989). From Assyriology to Renaissance Art. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133(3): 391-403

Oppenheim, A. Leo (1974). A Babylonian Diviner's Manual. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 33(2): 197-220

Rochberg, Francesca (1999). Empiricism in Babylonian Omen Texts and the Classification of Mesopotamian Divination as Science. Journal of the American Oriental Society 119(4): 559-569

- (2004). The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sachs, Abraham, Hermann Hunger (1988). Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia: Volume 1: Diaries from 652 BC to 262 BC. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- (1989). Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia: Volume 2: Diaries from 261 BC to 165 BC. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- (1996). Astronomical Diaries and Related Texts from Babylonia: Volume 3: Diaries from 164 BC to 61 BC. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Swerdlow, Noel M. (1998). The Babylonian Theory of the Planets. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Footnotes

Published in three volumes, Sachs and Hunger 1988; Sachs and Hunger 1989; Sachs and Hunger 1996.

Cited after Spek, http://www.livius.org/di-dn/diaries/astronomical_diaries.html. Hermann Hunger has a slightly different reading and amendment, cf. Hunger and Pingree 1989, 175–179. The content is fundamentally the same.

Edited by Hermann Hunger.